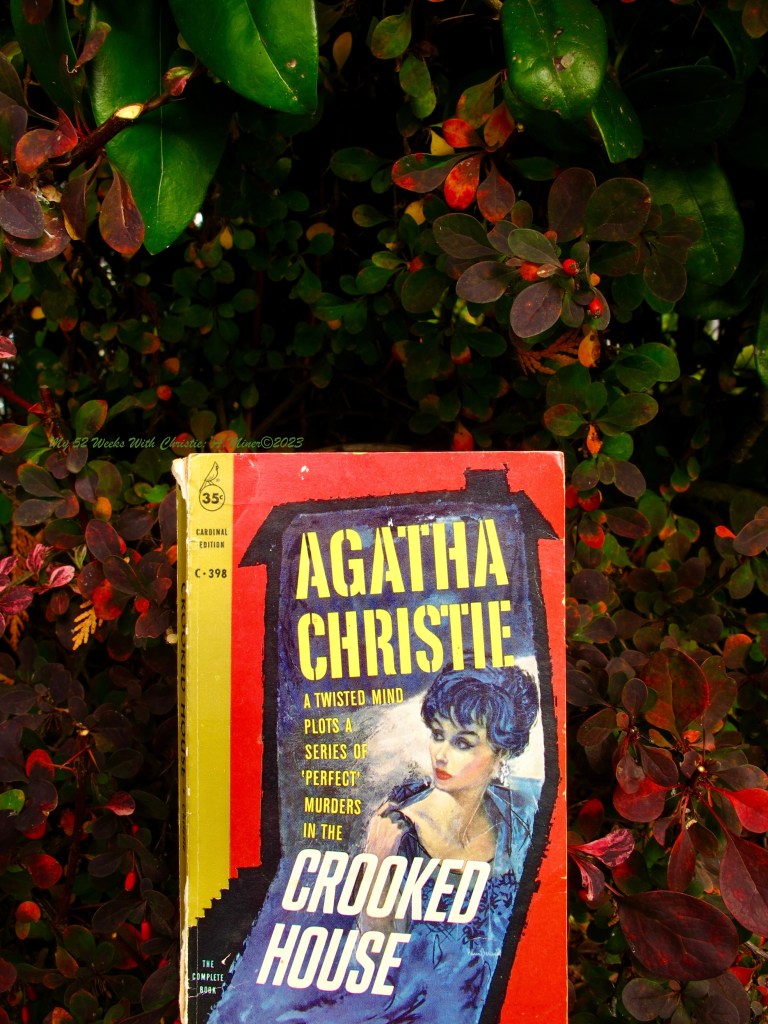

From the Office of Spoilers: If you’ve not read Crooked House by Agatha Christie, I suggest you do — then read my vintage true crime posts as one directly impacts the other. However, if you’ve no qualms with knowing the ending of a book before you begin it, read on. Either way, you’ve been warned.

Now, on with the show.

According to experts, far more learned than I, Agatha Christie’s publisher, William Collins (of Collins Crime Club fame), found the ending of Crooked House so shocking he requested Christie change it.

She declined.

By leaving the novel untouched, Crooked House now stands as one of the best twist endings in Christie’s entire catalogue of works (second only to The Murder of Roger Ackroyd — in my humble estimation). Though, on reflection, I’m not sure exactly why the revelation of Aristide Leonides’ murderer harkens such disbelief. Within moments of meeting our malefactor, they give us their motive; Charles Hayward’s Old Man practically spells out the whys & wherefores a few pages later, and Charles himself catches sight of the penultimate clue. Yet, for the past seventy-four years, the solution continues to blindside readers. And therein lies Christie’s cunning, the ability to mark and exploit our collective blindspots….…..Because how often, really, would you look at a kid and see a poisoner?

Turns out, more often than you’d think.

Some follow the pattern set by Crooked House’s thirteen year old baddie Josephine Leonides, whose motive for murdering her grandfather was his refusal to pay for her ballet lessons. By adult eyes, Josephine’s reason seems childish, and despite her being fictional — she’s not alone in this brand of flawed rationale. In my research for this set of posts, I’ve discovered kids who’ve killed because they were rebuked too often by their mother, because their father thwarted their ambition to become a train robber, and because they wanted to see if their “chubby” playmate’s insides resembled that of pig’s (that was a singularly gruesome crime).

However, it’s the crimes of Gertrude Taylor, a case I’ll explore in more detail in this series, which reminded me forcibly of Josephine’s puerile impulse to pick up a bottle of poison. Not only did she target her nearest and dearest, but she did so so her brother wouldn’t take his upright organ with him when he moved house.

Yet other kids find themselves following (roughly) in the obsessive footsteps of the Tea Cup Poisoner.

Graham Young’s fascination with poisons not only led to an in-depth study into the subject, at the age of fourteen he started experimenting with them….on his family and friends. In some respects, Young’s diabolical deeds are unique. His ability to dazzle druggists with his knowledge to procure deadly substances like thallium, antimony, atropine, aconitine, and digitalis sets him apart from most other child poisoners.

However, the overwhelming obsession that led to Young’s abominable “experimentation” is not.

Seventy years before and across the pond, another fourteen-year-old named Ella Holdridge found herself utterly transfixed, not by poisons, but by death. Whilst her family and friends considered it an odd fixation for a young girl, no one thought much about it. Until the summer of 1892, when, due to a distinct lack of local funerals she could attend, Ella took it upon herself to supply the local churchyard with a fresh corpse….Another case I’ll cover in the next few weeks.

Above and beyond Gertrude Taylor and Ella Holdridge’s ages, alleged crimes, and underdeveloped moral muscles — one more feature unifies this pair of kid killers: A self-made man who built his empire upon the back of dead rats.

Ephraim Stockton Wells.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023