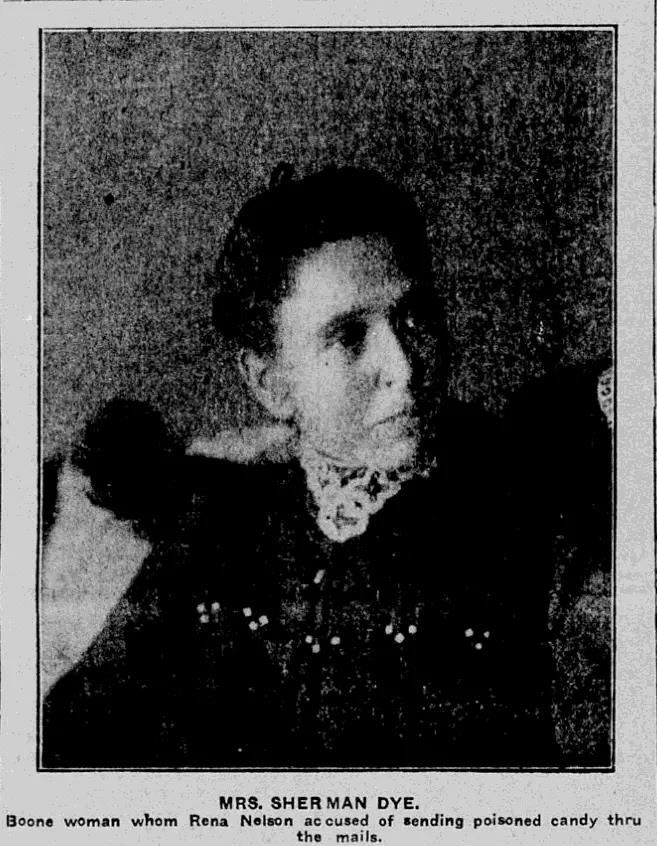

In an uncanny case of serendipity: While the curious citizens of Pierre, South Dakota, congregated outside the courthouse after the Coroner’s Inquest, someone linked to the investigation overheard a local confectioner remark that on Saturday, February 27, 1904, the day Rena Nelson said she received and ate a piece of poisoned candy — she’d come into his shop asking for an empty candy box. This tidbit marked the second inconsistency tallied that day. The first came during the testimony of one of the physicians, who noted That while a victim may linger in agony for upwards of fourteen days, the initial symptoms of an acute case of corrosive sublimate poisoning spring up within a few minutes or hours of ingestion. In other words, the science didn’t tally with Rena’s account of eating the tainted sweets on Saturday morning, feeling iffy on Sunday night, and then falling gravely ill on Monday morning. Compounding these two incongruities, Sheriff Laughlin admitted basing his pursuit of Belle Dye on Rena’s word — believing Rena’s sterling reputation provided the necessary veracity to establish his case.

So on March 10th (or perhaps 11th), authorities finally started corroborating the particulars of Rena’s accusation.

Pulling at the most straightforward thread first, investigators visited the shop of the confectioner whom they’d overheard earlier that day. Whereupon they learned that Rena did indeed stop by his shop looking for a candy box but left empty-handed as she said none that he stocked suited her purpose. Catching the scent, investigators visited a nearby drugstore, Dahoss & Company’s candy counter — and struck gold. Seems Rena bought a box and candy identical in every way to the ones submitted as evidence in the inquest.

Save for the white sweeties sprinkled amongst the chocolates.

Similar in shape and size to peppermint pastilles, it turns out they were, in fact, corrosive sublimate tablets.

With a sneaking suspicion starting to form, the lawmen returned to the beginning. Taking a closer look at the chocolate box’s wrappings, they found yet more discordant notes. While the package bore Rena’s name and address, they found it odd that someone would paste the front of an addressed envelope to the parcel rather than writing said details onto the paper wrapping itself. When the Special Agents from the Postal Service asked Pierre’s post office workers about this, they confirmed that Rena did receive a parcel on February 27th. However, they were nearly certain the box’s requisite information wasn’t listed on an envelope. When investigators rechecked the label again, using a strong magnifying glass, they detected writing beneath the pasted-down piece of paper (though they couldn’t read it). While back at square one, they also noticed a discrepancy in the cancellation marks. Seems the Boone Post Office cancels stamps using wavy lines, while this parcel’s stamps displayed a flag design. Even weirder, the box bore a January 23rd postmark. As a package doesn’t take a little shy of a month to travel the roughly four-hundred-and-seventy miles between Boone, Iowa, and Pierre, South Dakota, investigators re-interviewed Belle Dye.

Who readily admitted that she wrote Rena a letter in January.

However, when Rena did not respect Belle’s wishes to leave her and Sherman alone, so they could work things out, Belle went to the Boone Police Department. Requesting they arrest Rena, should she enter Boone’s city limits again — citing her continued interference in her & Sherman’s marriage. Though it’s unclear if they could actually do anything, Belle apparently felt confident they could, as she made arrangements with a mutual friend to notify her if Rena ever returned. Whilst also ensuring word of Belle’s plan to press charges reached Rena’s Aunt. Hence, the letter Rena received on the same day as the sweets. It warned Rena against writing to Belle again. Otherwise, things could get ‘hot’ for her.

Why would Belle resort to poison if she already had a plan in place to deal with Rena?

Finally, a report submitted by Boone police hardened the sneaking suspicion into a rock-solid certainty. No shop in Boone, Iowa, used boxes or wrappings like those on the box Rena received. Moreover, they’d run the type of bonbons Rena received to ground and revealed to their South Dakota counterparts no shop in all of Boone sold chocolates manufactured in Mankato, Minnesota.

Since, thanks to all the legal wrangling over warrants earlier, the lawmen already established Belle defiantly hadn’t left Boone for some time prior to Rena’s poisoning. And they doubted she’d any reasonable way of obtaining those specific candies, wrapping, or box. Put these facts together with the incorrect cancelation on the package itself, the odd method of address, and the exorbitant amount of time it took to supposedly arrive…Sheriff Laughlin admitted he now believed Rena Nelson had fashioned a plan to slightly poison herself and frame Belle for the deed.

While authorities never nailed down exactly where Rena obtained the corrosive sublimate tablets, though they suspected she swiped them whilst nursing the sick around the city (as the substance was used as a disinfectant in hospitals and sickrooms), they felt confident they’d finally arrived at the correct conclusion. (This time.)

Though they were less confident of Rena’s motivation.

Did Rena think if Belle went to jail, Sherman would be able to obtain a divorce from his wife, who, up until this point, had denied him one? Only to misjudge the amount of corrosive sublimate she could safely take (which, btw, is an infinitesimally small amount), destroying not only her chances of wedding Sherman but herself as well. Or did she sacrifice herself to ensure his freedom? Amongst the many articles I read, one claimed that Rena had shown her friends a letter from Sherman in November of 1903, in which he broke things off using the old saw — ‘he’d tired of her.’ This, of course, led to the report that Rena’s letter to her Aunt, the one she penned on Sunday, February, right before she became seriously ill, was tantamount to a suicide note.

Whilst no one but Rena knows the truth, I lean towards the former explanation.

Mainly because Rena wrote Belle asking her to grant Sherman a divorce — after — Belle had discovered the cache of Rena’s letters and photos in the family chicken coop in December. Implying Sherman told Rena they’d been found out. Information that wouldn’t need imparting if he’d broken up with Rena in November. On top of which, Belle herself was convinced Rena would return to Boone to visit either her or Sherman or both. Hence, Belle’s complaint to the police about Rena’s conduct.

It must’ve been a bitter blow to Rena when Sherman chose to comfort his wife in jail rather than running pell-mell to her side.

A choice Sherman repeated again…..eventually.

Seventeen months after Rena Nelson’s death, in August of 1905, Belle Dye started divorce proceedings and obtained an injunction against Sherman from seeing her or coming to their house. The reason? Apparently, Sherman continued running around Boone with other women, and when he condescended to stay home, he treated Belle with ‘extreme cruelty.’ (The papers speculating he blamed Belle for Rena’s death). However, by April 1906, Sherman had secured a good job with a railroad company in Denver. At which point, he invited Belle and his daughter Dolly (a nickname) to join him in Colorado, which they did. Whilst I’ve no clue if they were happy together, from bits and pieces I found in newspapers and census records, they did indeed stay together after their do-over out west until his death in 1951.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.