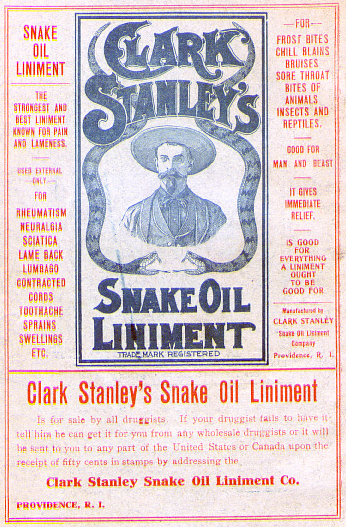

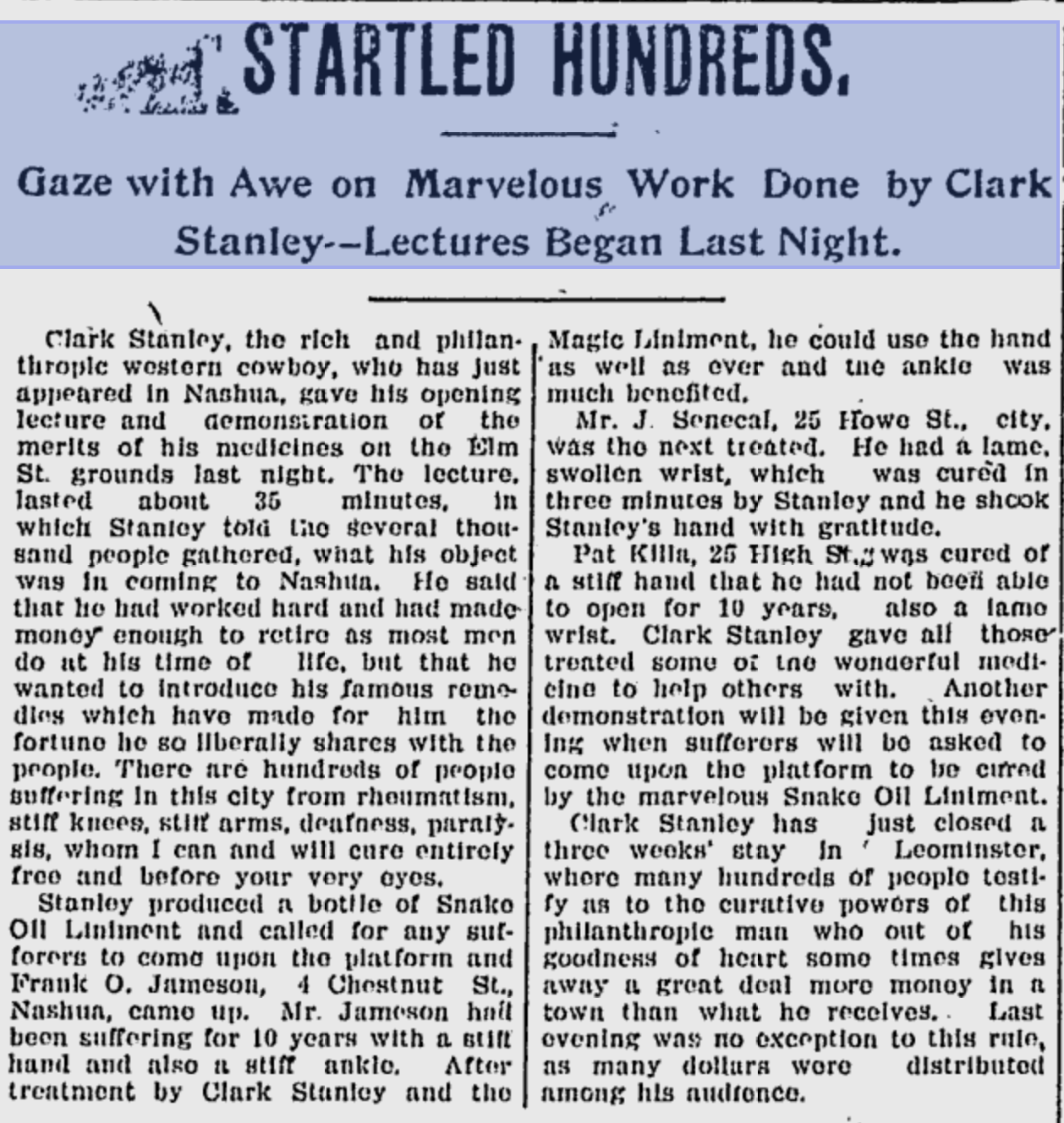

Ever wondered how ‘snake oil’ came to epitomize quack medicine? Or who the first snake oil salesman was? (Well, thanks to a great book called Quackery and some research, I can tell you.) During the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, a man named Clark Stanley took to one of the Fair’s many stages. Dressed in the height of frontier fashion, he produced a rattlesnake from a bag and then proceeded to slit it open in front of the crowd. Ignoring the blood and gore, Stanley plunged the snake into boiling water. Then he waited for the snake’s fat to rise to the surface, whereupon he skimmed it off, mixed it into a pre-prepared solution, stoppered the bottles, and sold it to an eager crowd under the name Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment.

Over the next twenty-three years, Stanley’s liniment would make him a fortune. Then came Upton Sinclair’s graphic and stomach-turning expose on the meat packing industry — which inspired the passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act.

From the title of the Act, you can guess where this is going.

The Drug portion of the Act allowed federal authorities to target patent medicines. These proprietary “medicines,” also known as nostrums, salves, powders, balms, elixirs, drafts, syrups, tinctures, essences, and liniments, DID NOT patent their ingredients or formulas. Instead, they trademarked their names, labels, packaging, and/or bottle shapes. Meaning that up until the 1906 Act of Congress, the hucksters of these “medicines” didn’t (generally) need to worry about doctors, chemists, or other interested parties testing their effectiveness. Hence, manufacturers rarely placed an ingredient list on their products or, like Stanley’s Liniment, only provided one or two key (usually “exotic”) components. Whilst claiming they’d cure you of everything from the common cold, aches & pains, cancer, sexually transmitted diseases, and death — amongst other things.

Yeah……You laugh, but common sense often gets tossed out the window when desperation settles in for an extended stay.

In any case, Stanley got away with selling his Snake Oil Liniment until May 20, 1916. When crates of his Snake Oil, bound for Massachusetts, were seized by federal authorities and analyzed by the Bureau of Chemistry. In short order scientists revealed Stanley’s secret formula: “light mineral oil (petroleum product) mixed with about 1 per cent of fatty oil (probably beef fat), capsaicin, and possibly a trace of camphor and turpentine.”

Unsurprisingly, not a single microscopic mote of snake, rattle or otherwise, was found within the liniment.

As these ingredients did not cure pain, lameness, rheumatism, sciatica, paralysis, inflammation, animal & insect bites, or reptile/insect/animal poison — as the Snake Oil literature claimed…..Led Stanley to plead nolo contendere (which means Stanley accepted the conviction as if he pleaded guilty without actually admitting he did anything wrong) and pay a twenty-dollar fine (about $576 in today’s money).

Now, by comparison to the majority of his contemporaries who used things like grain alcohol, cocaine, opium, morphine, strychnine, lead, uranium, and radium in their products — Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment was pretty safe (if one followed the recommendation on the advert — “Used Externally Only”). The problem was anyone who picked up a newspaper back then was inundated with adverts for these dodgy cure-all concoctions — because the ad revenue they generated paid the bills.

Enter Ephraim Stockton Wells.

By the Spring of 1862, Ephraim owned and operated a drugstore on Monticello & Harrison Avenue in Jersey City, New Jersey. One day, whilst he was helping customers in the front of the shop — rats tucked into his lunch in the back. Upon discovering the sad remains of his midday meal, Ephraim vowed revenge on the vermin who’d left him with an empty stomach. Drawing on all his knowledge of chemistry and drugs, Ephraim concocted a deadly compound to rid the world of the rodent scourge. When he told his wife of his plan, she joked about him being rough on rats — and the name stuck. (This origin story, of which there are several variants, probably contains a small kernel of truth.)

From 1863 to 1880, Rough on Rats would be Ephraim’s side hustle.

Initially, Wells only sold the deadly rodenticide at his Jersey City drugstore. Then, perhaps, after casting an eye across the shelves of patent medicine his store stocked and his customers bought by the bag full, Ephraim recalled an episode from a few years earlier. After the NYC drugstore he worked at unexpectedly folded, Ephraim placed an advert about himself in a newspaper, and by the next week, he’d a job in Michigan. Either inspired by these real life events or simply following in his contemporaries’ footsteps — Ephraim patented the name Rough on Rats. And in a stroke of genius or foresight, Ephraim also patented similar sounding names, to thwart future competition. (Moreover, Ephraim would end up employing a veritable fleet of lawyers to defend his trademarks.) With his brand now secure Ephraim moved onto phase two, and between 1872-1880 he spent forty-thousand dollars (which is just shy of 1.2 million dollars in today’s money) advertising Rough on Rats in newspapers across the country.

This ambitious gamble nearly bankrupted him.

However, by 1881, Ephraim’s investment paid off. Allowing him to sell his drugstore, convert another property into a manufacturing facility, and focus all his energies on growing his mail-order business. Which he did with relish. Not only did Ephraim place $140,000 worth of adverts, of his own design, in every magazine and newspaper he could think of every year for the next twelve years — he also expanded his empire into England, New Zealand, and Australia. Seeking trademark protection in each new country to once again keep “imitators” at bay.

The only problem? Ephraim’s multi-national trademark hid a dirty little secret: Rough on Rats’ primary component was white arsenic.

Known since Cleopatra’s time, refined by the Borgias, and made cheaply available via the Industrial Revolution — by 1862, everyone from emperors to paupers knew of arsenic’s legendary lethality. (Thereby making Ephraim’s claim he “used all his knowledge of chemistry and drugs” to concoct his popular product a bit of a stretch.) And despite Rough on Rats failure to disclose its secret ingredient, it didn’t take long for the general public to work out that Rough on Rats worked just as well on humans as it did on vermin.

This omission, when taken in conjunction with Rough on Rats adverts, poses an ethical conundrum — i.e. how much responsibility should Ephraim Stockton Wells shoulder in the hundreds, if not thousands, of non-rodent related deaths connected to Rough on Rats?

In the majority of murders linked to the rodenticide, I’d agree Ephraim’s conscience is clear — except — in one narrow category: Where kids purchased, administered, and murdered with Rough on Rats. Whilst regulation on the sale of arsenic were inconsistent at the state level in the US — by 1872 (the start of Rough on Rats heyday) most restricted the sale of arsenic to minors. Meaning, Ephraim’s omission allowed kids to buy poison they’d otherwise be denied.

A flaw in the law which Gertrude Taylor slipped through in 1896.

My 52 weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023