Dubious of Gertrude’s lucky escape, Dr. Kaltenbach swiftly sussed out Gertrude’s choice of water over coffee was inconsistent with her regular suppertime eating habits. With this nugget of knowledge stuck in his craw, Dr. Kaltenbach continued to care for the rest of the poison-stricken Taylor family — who now needed to contend with making funeral arrangements for their patriarch, Dillon. And whilst they and the extended family handled those details — Dr. Kaltenbach quietly started piecing together a case against Gertrude.

Knowing he’d need more than his gut feeling and deductions to accuse any member of such an influential family, especially a thirteen-year-old girl, Dr. Kaltenbach set about confirming the coffee was indeed how the poison was administered.

Now For a Deduction On My Part: Whilst the gold standard in detecting arsenic, the Marsh Test, had been around since 1836, there’s a good chance a small-town general practitioner had never performed it. It’s also equally possible Dr. Kaltenbach simply didn’t have the time to conduct the highly sensitive test — as he’d seven or eight seriously sick people to treat whilst trying to keep a weather eye on his prime suspect and the extended family from entering the sickrooms (just in case he’d honed in on the wrong person).

Either way or both, Dr. Kaltenbach decided he only needed to prove poison was present in the coffee for the inevitable inquest into Dillon Taylor’s death, so after securing and spiriting away the leftover coffee from the pot and its dredges for later analysis. He then poured the remnants from the family’s coffee cups into the slop buckets of three hogs and fed them the adulterated mash. When the poor piggies exhibited the exact same symptoms as those experienced by the Taylor family and died — Dr. Kaltenbach knew he’d proven the first portion of his theory.

Which, of course, led to the inevitable question: Where did Gertrude get the arsenic?

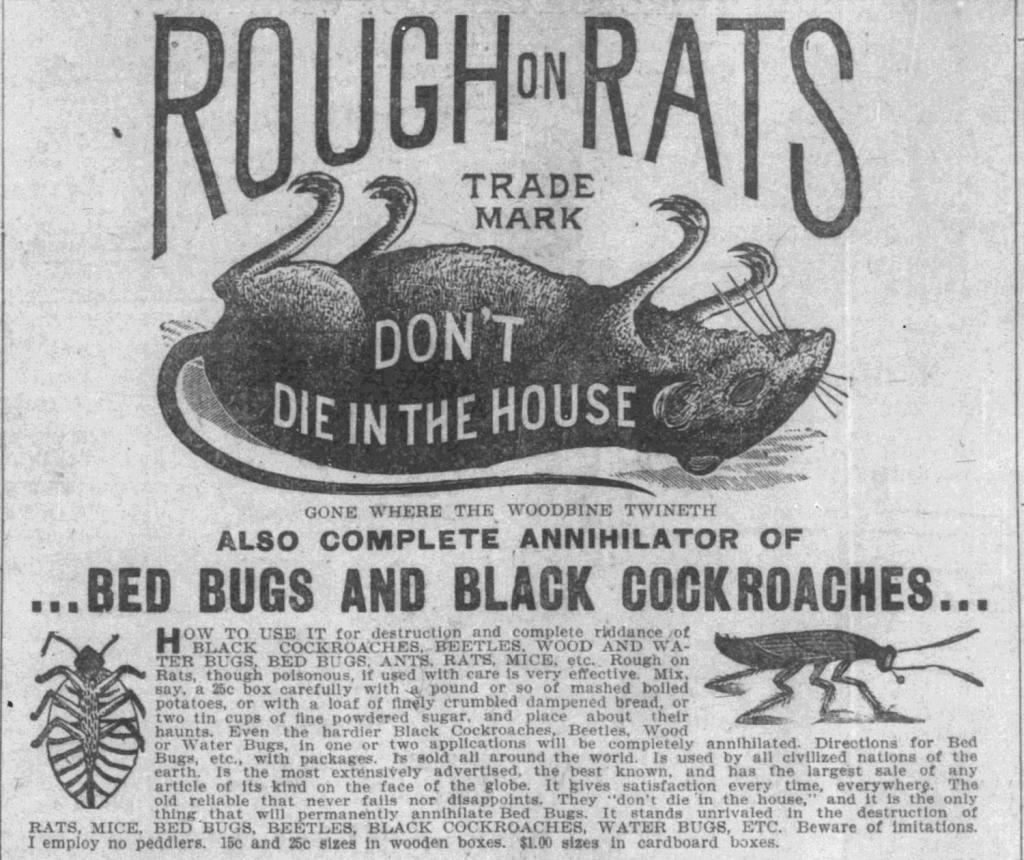

Assuming he’d a quiet nose around the obvious places one would store caustic chemicals in a home, without finding any, Dr. Kaltenbach moved on to the next obvious means of acquisition — the town druggist. Turns, mere hours prior to the mass poisoning, Gertrude visited the drugstore and bought a bar of soap and a box of Rough on Rats.

With the druggist William Butts’ information in his hip pocket, Dr. Kaltenbach confronted Gertrude.

At first, Gertrude lied and flat denied possessing Rough on Rats. When Dr. Kaltenbach pressed further, telling her he knew she’d bought a box, she eventually admitted to the purchase. With that established, Dr. Kaltenbach asked where it was, and Gertrude told the doctor she’d secreted it away upstairs. Sending her to fetch it so he could (presumably) inspect how much of the rat poison remained — Gertrude left and never returned. A short time after he’d been left hanging, Dr. Kaltenbach asked Gertrude’s Aunt, Mrs. Ada Sharp, if she could get Gertrude to divulge the information. A task which Mrs. Sharp was only partially able to complete as Gertrude refused to tell her Aunt why she’d bought Rough on Rats, though she did confess to losing the box on the way home.

Armed with all this information, Dr. Kaltenbach related what he’d found out and witnessed during the Coroner’s Inquest held on March 17, 1896. This, in turn, resulted in the exhumation of Dillon Taylor, who’d been buried four days before, for a post-mortem. (During which Dillon’s stomach was removed for chemical analysis….Said testing was performed around May 5, 1896, and the chemist found not only arsenic but powdered glass in Dillon’s organ as well. When the chemist compared what he’d discovered in Dillon’s stomach to a box of Rough on Rats, purchased specifically for this test, the results aligned perfectly. As the fresh two ounce box of Ephraim Well’s rat poison contained about one ounce of powdered arsenic and the rest was powdered glass and starchy substances. The chemist went on to posit each cup of coffee contained about 20 to 24 grains of arsenic — more than enough to kill a man.)

The coroner’s jury also returned a verdict naming Gertrude as the one responsible for her father’s death.

On March 19, 1896 — Gertrude was arrested.

Thanks to a few remarks made to the press prior to the hiring of defense lawyers — we learn that Green Taylor, Dillon’s brother, “….was determined to sift the crime to the bottom and to prosecute the guilty person to the end.” To my ear this sounds a lot like a man who has a doubt or two about his niece’s innocence — but is smart enough to only allude to them when speaking with reporters. However, unlike Edith de Haviland, whose clarity of sight and strength of character allowed her to see what the rest of her family couldn’t or wouldn’t admit to themselves and then act on it, Green Taylor either ended up holding his tongue when he realized thirteen-year-old niece might hang or was persuaded into swallowing Gertrude’s story.

Whichever way, by the time Gertrude went to trial in May of 1896, Green Taylor sat with his other brother in the court — supporting his niece.

If any influence was exerted on Green Taylor, to shift his stance at least in the public eye, was undoubtedly brought to bear by Gertrude’s other Uncles — A.C. & Arthur Sharp, Gertrude’s mother’s brothers, and most vocal supporters. Not only would they not listen to a word said against their niece, they paid the thirteen-year-old’s $1,000 bail (about $36,000 in today’s money), financed her defense, and told a reporter Gertrude “…would never be convicted if money can save her.”

As the entire Sharp family was extremely wealthy and prominent in Missouri society — this wasn’t an idle boast.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023