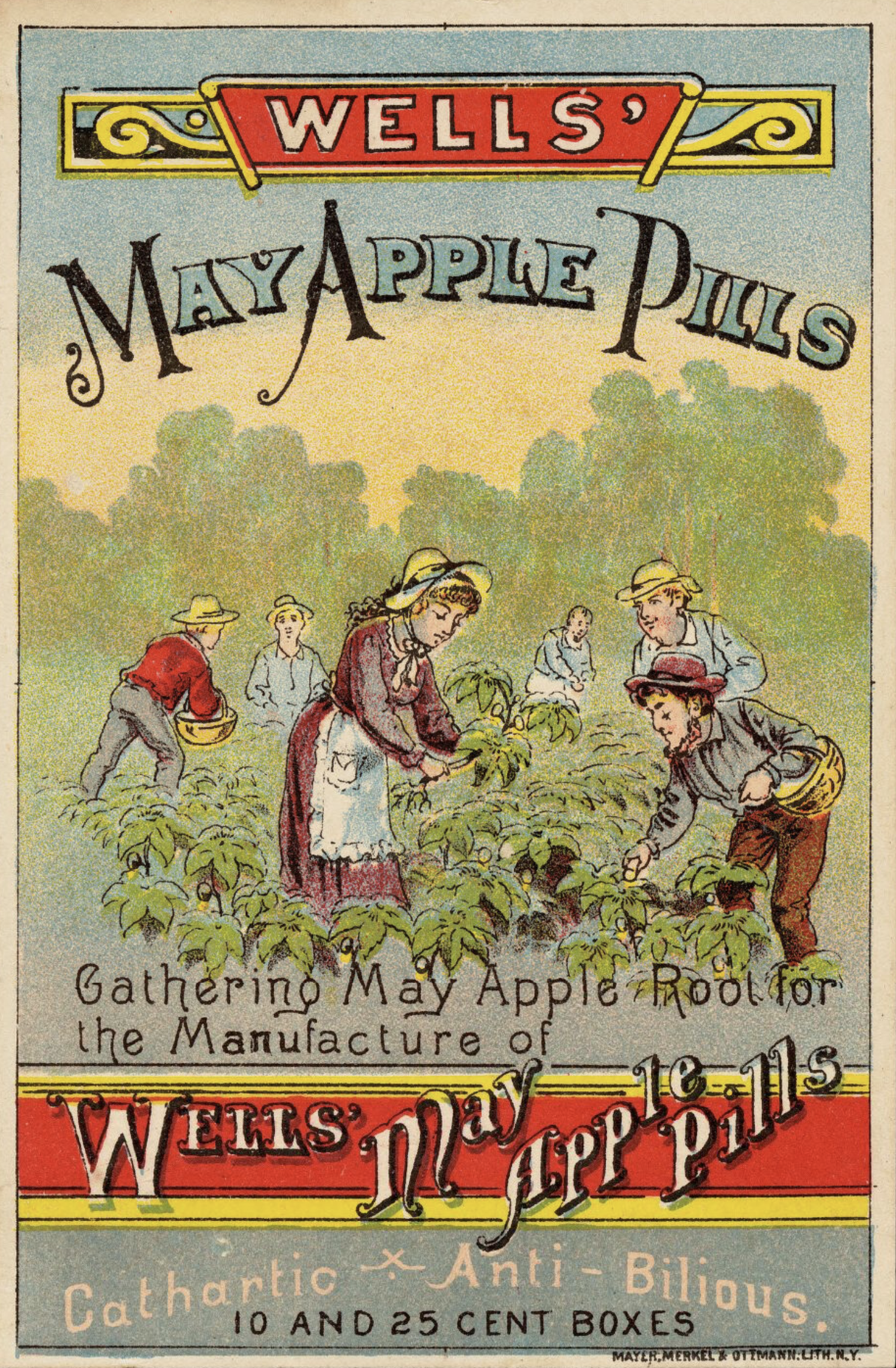

Since using dangerous and/or addictive compounds in patent “medicines” was common and we know Ephraim had large quantities of arsenic on his hands, I wonder how many of his other products contained traces of this dangerous element. A number of the claims made in the ads for Wells’ beauty aids and “medicines” sound remarkably similar to the effects (the crazy people during the Victorian era) achieved by applying arsenic to their skin or by eating small quantities.

Though I’ve no clue if Ephraim Wells added arsenic to any of his pills, tonics, or syrups — I do know what he put in Wells’ Hair Basalm for Gray Hair:

“…a perfumed mixture of sulphur with aqueous solution of lead acetate and glycerol…”

In 1912, the US government via the 1906 Pure Foods and Medicines Act caught up with Ephraim’s claims that his basalm was “harmless and not a dye.” The chemists not only proved the basalm contained dye but also consisted of lead. A heavy metal that was finally proven highly toxic in the mid-1800s. Making me wonder how many women suffered lead poisoning from the habitual use of Wells’ basalm.

In any case, Ephraim plead non-vult or no-contest to the charge. Though, unlike the majority of his contemporaries tried for similar offenses, the court didn’t levy a fine against Ephraim.

Probably, and this is speculation on my part, because he was pretty sick at that point in time.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023

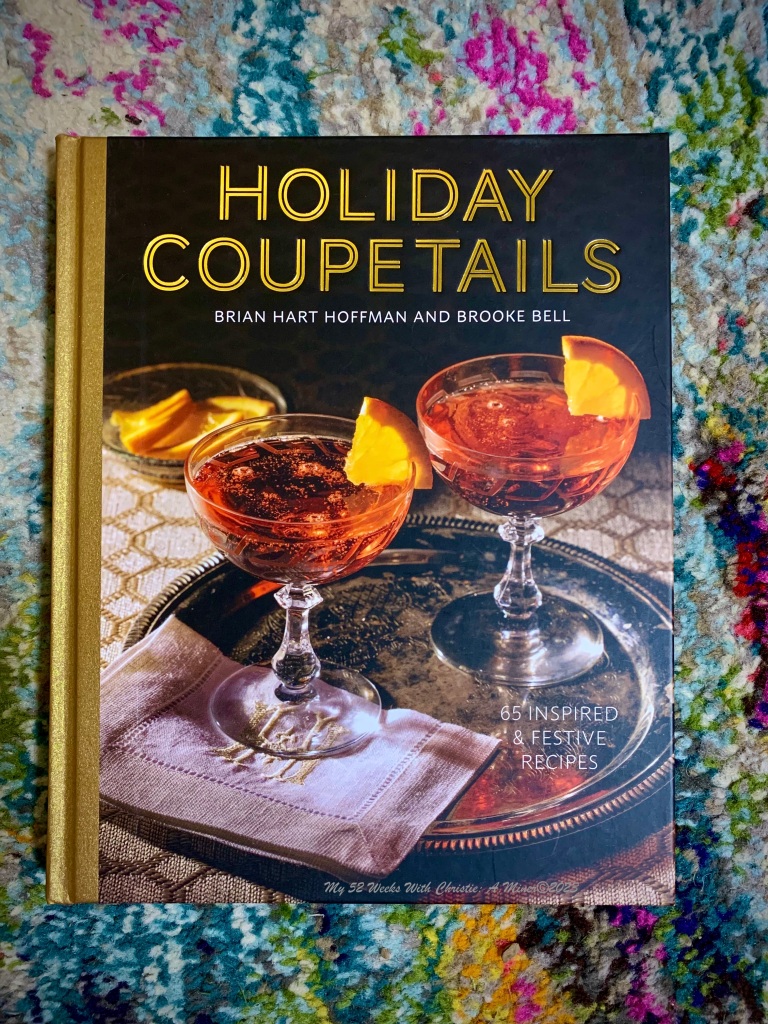

Inspiration: Perusing one of my favorite baking magazines a few months back, they advertised an upcoming cocktail book that looked interesting — Holiday Coupetails. Trusting the editors of Bake From Scratch, I gave the book a go…and am delighted that I did.

Not only does Holiday Coupetails have drink recipes, but it also gives instructions on how to make the garnishes and some fun, festive nibbles!

Even better, Hoffman and Bell (the authors) give the basic recipe for said drink garnishes, allowing you to dress them up as you see fit. This focus on the basics is a refreshing change from the recipes for things like dried citrus peels you find on the internets, which tend to be either overly complicated or assume you’ve got specialized equipment (like a dehydrator).

In any case, this cocktail turned out great! On my second try….

Learn From My Mistakes: When making it, do not put in an equal amount of blood orange juice to that of the other ingredients. The extra sweetness totally flattens the taste of the Campari and makes the cocktail somewhat dull. As they instruct in the book — a single squeeze is enough!

Christie: This is a drink I could see Poirot or Mr. Satterthwaite enjoying — as it is both bitter, sweet, and sophisticated. More importantly, since one version or another of this cocktail has been around since the 1920s, it means either gentleman could easily have ordered a negroni on their travels.

(Head in the sand or in this case underwater….)

Whilst it’s impossible for me to say if Ephraim Stockton Wells was aware of either Gertrude Taylor or Ella Holdridge, I cannot imagine him unaware of the unintended consequences of his patent product. Accidental deaths, suicides, and murders abounded for years in “all civilized nations of the earth” where Rough on Rats was sold. The comic below, which he included in one of his ads, proves at least by 1901, Ephraim knew of one common misuse of Rough on Rats.

At best, including this comic strip was in poor taste. At worst, it shows his contempt for the multitudes of people who’d used his product for this purpose.

More likely, and this is conjecture on my part, he was thumbing his nose at all the physicians, lawyers, and scientists who’d criticized him and Rough on Rats for DECADES. Not only did they take exception to the lack of information about Rough on Rats’ composition on the label. (Remember it was a patent product: Meaning the name, not the formula, was trademarked. Hence, it did need to include this info.) These professionals also laid a portion of the blame for the product’s misuse at his door.

And I don’t think they are wrong.

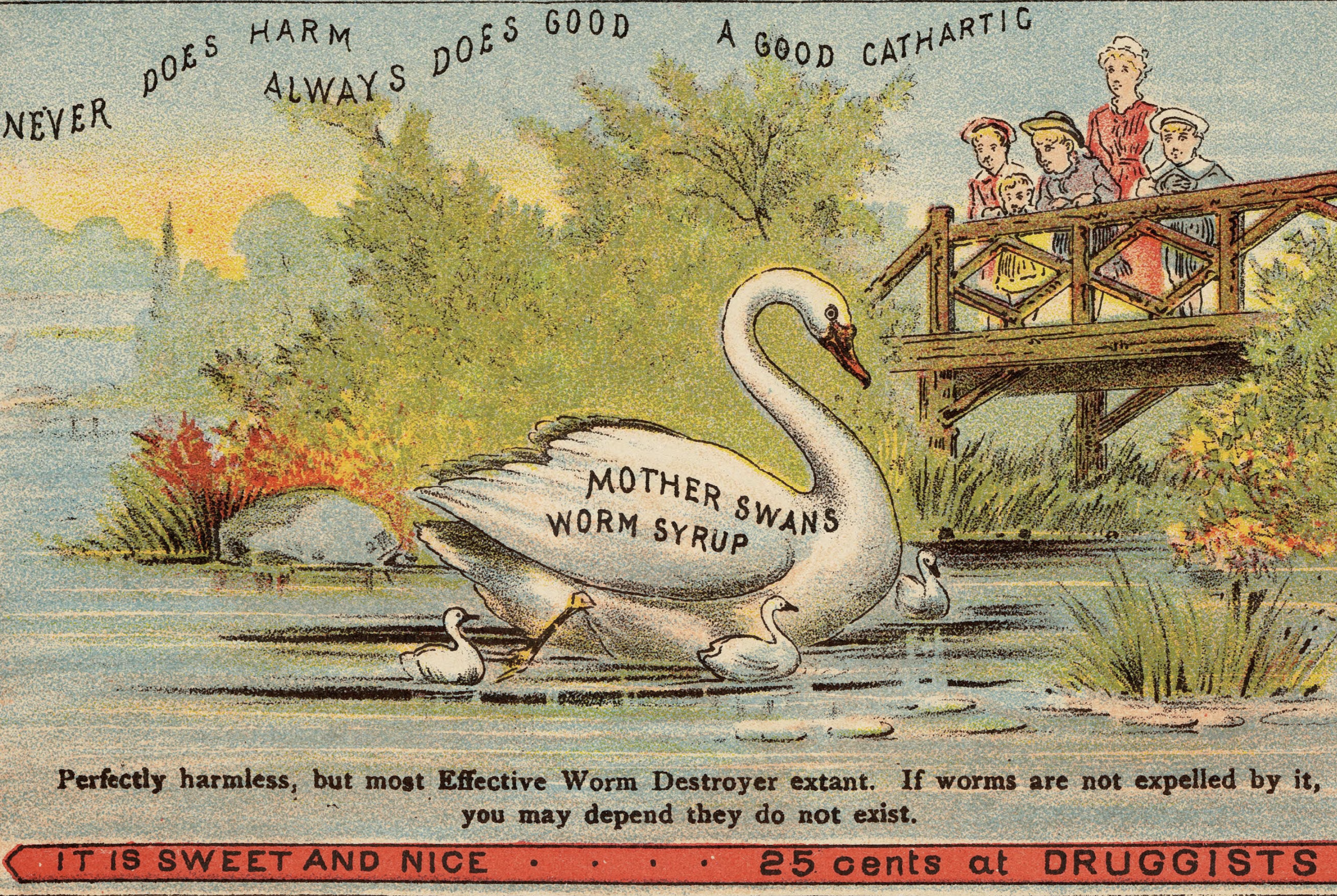

Very few ads, which Ephraim Stockton Wells proudly boasted he wrote and illustrated himself, mention Rough on Rats in the same breath as poison. In fact, the only ones I found that clearly state Rough on Rats is a poison was after 1901 when state governments started catching up with what their residents had already figured out: Rough on Rats killed people just as well as rodents. And started requiring Ephraim’s most popular product (and those like it) be “plainly labeled as poison.”

Which he did.

However, Rough on Roches, Ants & Bedbugs — and — Rough on Moth, Fly & Flea are clearly marketed as non-poisonous. The only problem is, up until now, Rough on Rats claimed to kill these same pests. While I suppose it is possible Ephraim changed his formula to something akin to Diatomaceous Earth (a non-toxic substance that can deal with these bugs), which started being mined in Germany around 1863, I’m not totally sold on the idea he swapped formulas as, as far as I can tell, Ephraim still didn’t disclose the ingredients for either of these insecticides. Though, in fairness, I’ve not found them linked to any human deaths.

Above and beyond Ephraim’s failure to disclose arsenic as Rough on Rats’ primary ingredient, I think what critics really took exception to was his recommended mechanisms for delivering Rough on Rats to rodents and other pests.

One of the main difficulties facing any rodenticide is poison shyness.

Poison shyness is where rats and mice learn to associate the smell, taste, or similar types of food with becoming sick after eating it. (Hence, why they nibble at food before wholesale scarfing ensues.) Once said aversion is triggered, it can take weeks or months for rodents to forget why they won’t snack on whatever made them sick. This explains why premade poisonous pellets, cakes, and blocks rapidly lose their effectiveness.

Ephraim skirted this thorny problem by asking his customers to mix their own bait. For indoor mouse issues, he suggested blending Rough on Rats with bacon grease, lard, or butter, then spreading it on a piece of bread or meat. Upon completing this step, he instructed his customers to place the adulterated food wherever they’d seen them scurrying around in the past.

As strategies go, it’s sound.

By giving your vermin morsels they’ve already taste-tested, you avoid triggering their evolutionary adaptation. Unfortunately, despite the bit of coal dust added in for coloring to help make Rough on Rats’ addition to food & drink more obvious, in the middle of the night, bleary eyes accompanied by a growling stomach only see the triangles of buttered bread left on a kitchen counter as a tempting snack — not as bait. (BTW: This really happened and the midnight-snacker didn’t make it.)

Then, there’s the secondary poisoning risk presented by Ephraim’s directions for dispatching sparrows, squirrels, chipmunks, skunks, gophers, and moles. He asked customers to combine the thinly disguised powdered arsenic with cornmeal or boiled potatoes and then spread the amalgamation about the yard, field, or undergrowth. This method, of course, led to numerous pet and livestock deaths.

Moreover, prior to Rough on Rats’ 1901 schism from insects, Ephraim’s instructions on how to administer the Rough on Rats to eradicate infestations of flies, fleas, ticks, lice, gnats, water bugs, ants, cockroaches, beetles, potato bugs, and bedbugs virtually ensured accidental exposure (and sometimes death) to pets, children, and adults. Because no matter how carefully one crams arsenic-laded grease into the seams of a bed frame, floorboards, or baseboards — you either get the stuff on your fingers during the application process, while you sleep, or walk across the floor. (To deal with bedbugs, fleas, and beetles.) Never mind dusting shelves in pantries, cupboards, or inside kitchen drawers with a mixture of confectioners sugar and Rough on Rats. (To dispatch cockroaches and beetles.)

These widely published methods of assassinating pests, in a roundabout way, also gave the idea of how to dispatch other humans. Because if rats didn’t taste the poison, how could humans?

So, while you could argue Ephraim’s doesn’t bear all the blame for the deaths linked to Rough on Rats….his conscience isn’t exactly clear either.

Though whether or not Ephraim felt this burden is unknown, as according to people more learned than I, he didn’t leave any writing (open to public perusal at least) on the subject upon his death in 1913. Nor did his sons, who’d taken over the day-to-day operations of Ephraim’s empire around 1903.

Happily, Rough on Rats eventually faded from store shelves and popularity as other rodenticides and pesticides surged in popularity. (DDT, Thallium, and Warfarin, for example — all of which caused their own chaos.) In 1955, Ephraim’s family sold the brand Rough on Rats to Brown Manufacturing Co. in Le Roy, New York. They, in turn, went out of business sometime in the sixties.

Ending Rough on Rats reign.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023

Inspiration: In an attempt to declutter her house, my mom unearthed a family cookbook from the attic. Well acquainted with both my enthusiasm for baking, vintage cookbooks (especially family heirlooms), and old recipe boxes I find at thrift stores — my mom made a point of saving the handwritten culinary history of our family for me.

The above recipe comes from my great-grandmother, who managed a cafeteria for decades and it also happens to be one of my husband’s favorite cookies. So, I decided to whip them up as a treat for him and his colleagues at work.

What I like most about sour cream cookies is their tang and the fact they aren’t overly sweet. (Don’t read savory here. They aren’t. The cookies just don’t shock you with sugar.)

Christie: For once, I got the right book with the right recipe! I think Miss Marple would enjoy eating and serving these cookies immensely.

This is a baked lemon chicken which was only okay…and since I haven’t figured out how to make it better (for our household at least) I decided just to just publish the pic — which was better than the actual chicken thighs.

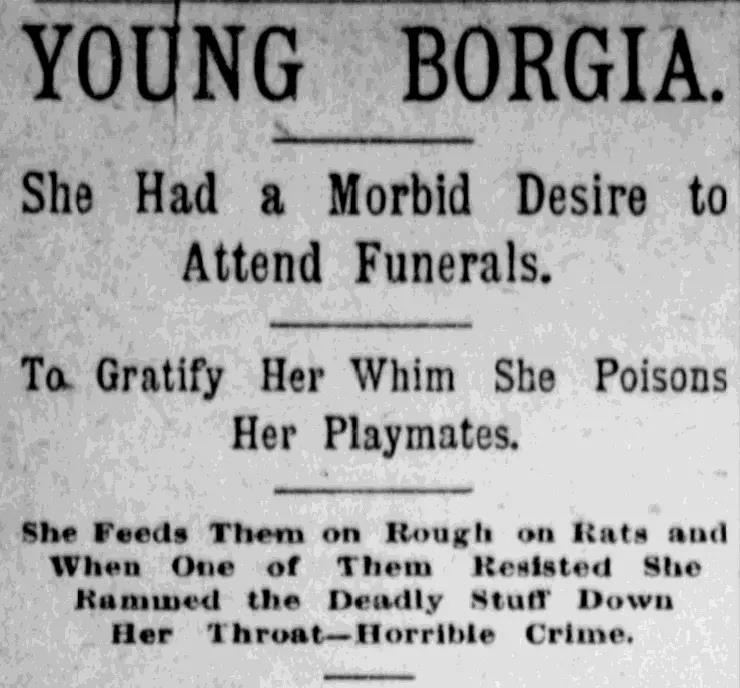

Flush with success and brimming with confidence over her first induced funeral, Ella Holdridge waited (about) five days before feeding her obsession with death, funerals, and wakes.

Only this time, Ella made a mistake.

Whilst plenty of people noticed the two girls playing together on the day Leona fell ill, no one for a moment suspected Ella played a role in the toddler’s lingering death. Mainly because of the two-year-old’s inability to utter anything sensible after ingesting the water Ella polluted with Rough on Rats.

However, this time, Ella targeted a pair of sisters — Susie & Jennie Eggleston.

Due to the sensationalization of this case, there’s some ambiguity on what exactly happened next. (Newspapers of this era absolutely loved to hype up crimes like this — often at the expense of the facts.) However, these things seem certain: In and around July 16, 1892, Mrs. Eggelston decided to go shopping in Buffalo, NY (about twelve miles from their neighborhood in Tonawanda) — leaving her daughters at home. Now, one way or another, either knowing beforehand via the neighborhood grapevine or sussing out the intelligence from the pair as they played on their front porch — Ella realized the lack of adult supervision afforded her an opportunity to generate a double funeral.

Using her status as an older kid (as she was fourteen to their ten and five) and the promise of making them “something nice,” Ella managed to herd the two inside their house. After (possibly) locking the doors after they went inside, Ella made a pot of cocoa with a generous measure of her secret ingredient, Rough on Rats, thrown in. When one of the sisters complained about the cocoa’s taste and refused to drink anymore, Ella compelled the girl to drink it: Through either verbal coercion, pushing her onto a sofa and pouring it down her throat, or throwing her onto the floor and forcing the liquid between her lips. After ensuring Susie and Jennie finished their mugs of cocoa, Ella told them not to tell anyone about what happened and left.

Later that evening, both girls became extraordinarily ill and their parents sent for Dr. Edmunds.

As both Susie and Jennie had been the picture of health prior to their mother’s trip into Buffalo and they’d pretty much identical symptoms which started nearly simultaneously — Dr. Edmunds suspected they’d gotten into something poisonous. Can you imagine his surprise upon learning about Ella’s strange-tasting hot chocolate and even stranger behavior? Then word reached him about another kid a few doors down who was desperately sick — with the same symptoms as the Eggelston sisters.

Seems sometime during the day, Ella also administered some Rough on Rats to five-year-old Ervin Garlock.

Whilst doctors worked diligently to save the lives of the three kids — news of Ella’s possibly poisonous food and drink spread like wildfire around the neighborhood of Kohler and Morgan Street. Leading every parent hither, thither, and yon to interrogate their children as to whether they’d eaten anything given to them by Ella.

After Susie, Jennie, and Ervin’s lives were back on solid footing, Dr. Edmunds and Dr. Harris compared notes….and discovered Leona’s symptoms mirrored those of the other poisoned children. Unsurprisingly, the duo of doctors took their suspicions to Justice of the Peace Rogers and Coroner Hardleben — who called Ella in for questioning posts haste.

At first, the fourteen-year-old denied everything.

However, when one of the officials bluffed and told Ella someone had seen her making the cocoa, and they knew she’d put poison in it — she opened her eyes wide and said….“Dear me, is that so?” And went on to make a full confession. Telling the adults she’d poisoned Susie and Jennie: “…because she wanted to go to a funeral, and thought they would look so nice dead.” When they asked after Leona’s murder: “Yes, she’s dead. Poor L{eona} But she looked awful pretty and her funeral was awful nice.” When Justice of the Peace Richard asked why she used Rough on Rats, Ella replied: “If it killed rats and mice it would kill children.”

(Prompting authorities to exhume poor Leona’s body and send her stomach to Dr. Vandenbergh for analysis.)

On July 16, 1892, Ella was charged with murder.….and this is where things get a bit murky.

I know on July 18, 1892, Franklin Holdridge (Ella’s Dad) committed Ella to the care of Father Baker’s Institution at Limestone Hill. I believe the “institution” the papers referenced was a protectory.

(The above picture was printed in an atlas about thirty-five years prior to Ella’s hasty trip to said Institution.)

Protectories are akin to nonreligious reform or industrial schools. They took in all kinds of kids, from orphans to juvenile delinquents — educated them in religion, morals, and science, then trained them in a trade or for a manufacturing position. Whilst not a prison, Father Baker’s protectory would afford far more supervision and possible rehabilitation for a budding poisoner. (It undoubtedly gave Ella space from her obsession because I can’t imagine the nuns or priests in charge would’ve allowed her to attend funerals or visit the graveyard — given her history.)

In any case, this prompt change of address not only kept the children in Ella’s old neighborhood safe, including her much younger siblings, it might’ve also (possibly) given the jury a reason to find her not guilty.

I say possibly because, unfortunately, I can’t find any direct news pieces on Ella’s trial. Save a blurb written just under eight years after the events of July 1892. It states that despite Ella’s confession and testimony in which she reiterated her belief that Leona and the others would “…look well dead…” a “…jury didn’t see fit to punish her.”

Perhaps Ella pleaded insanity? Or, due to her age, her lawyers argued she didn’t understand the enormity of her actions? Or maybe they didn’t want to send a pretty young girl to jail for the rest of her life. I don’t honestly know. However, I suspect it didn’t hurt that of her four victims — Susie, Jennie, and Ervin managed to live through the ordeal she put them through.

I also reckon Ella remained in Father Baker’s care for a spell after her trial, though this is purely conjecture on my part. (Mostly because I can’t see a way for her to return home to Tonawanda after killing a child, no matter the outcome of a trial. Though again, it is possible.)

(Ella, from later in life. From findagrave.com)

However, I do know that by the time Ella was about 24, she was married to a man named Neil McGilvray with a baby daughter on the way. In 1905, they had another daughter. In 1908, the family moved to Monessen, Pennsylvania, where Ella would remain for the next 37 years until her death in 1945 at the age of 65.

You must be logged in to post a comment.