‘A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down. The medicine go down. The medicine go down…’ Originally, this ditty sung by MaryPoppins meant to teach her charges how changing their perspective could make any task fun — and as a kid, I lapped Ms. Poppins’ lesson right up. Not long after, my folks skewed the song’s meaning to a more literal interpretation, i.e., taking actual medicine. (Without giving me an actual spoonful of sugar or some other substitute — much to my younger self’s disappointment.) This ever-so-slight adjustment introduced the idea that songs, art, and books could take on new meanings separate from the creator’s original intent.

Fast forward a few decades to the day my brain took this ditty’s refrain one step further by wondering if A Spoonful of Sugar shouldn’t be absinthe’s unofficial anthem. After all, absinthe did originally start out as a medicine (whether or not it was effective treatment is a different story), and the ritual around consuming the notorious spirit does often include a sugar cube…..Set on a slotted spoon which rests upon the rim of a glass which contains absinthe. When all the elements are assembled in the correct order the water dripper is turned on and the sugar cube is gradually dissolved — one water droplet at a time.

A Pic of a picnic with absinthe cocktails in tow.

(Fun Fact: A Spoonful of Sugar owes its origins to the songwriter’s son, who inspired his father with how he received his polio vaccine.)

What’s the point of waiting ages for the sugar cube to completely dissolve?

Not only does the sugar sweeten and round out the taste of absinthe (according to experts) — you’re rewarded with the pageantry of the ouzo effect. Otherwise known as louching, as each drop of water falls into the absinthe, the ice cold drip steadily transforms the crystal clear green liquid into cloudy opalescence. This unhurried ceremony forces the imbiber to slow down, be patient, and present in the moment. Lessons which I think Mary Poppins, who herself enjoys the odd glass of rum punch, would approve.

An absinthe water dripper & specialized spoons.

Interestingly enough, this pomp & circumstance around drinking a dram of absinthe was perfected by the French during decades spanning the mid to late nineteenth century. Culminating l’heure verte or the green hour, where people would flock to their favorite drinking joint from five to seven pm and partake in absinthe’s relaxed razzle-dazzle.

(Fun Fact: L’heure verte is the precursor to what we now call Happy Hour.)

A pic from 1916 of Valentin Magnan.

Yet not everyone in France was spellbound by absinthe’s sedate charm. The man considered the foremost authority on mental illness (upon his appointment to the post of physician and chief of Sainte-Anns asylum in 1867), Valentin Magnan, held absinthe responsible for the overall decline of the French people. He also believed this degeneration via absinthe (and alcohol in general) was passed on genetically from one generation to another — and was inevitable. He came to this conclusion due to the uptick in those admitted to his asylum and the study of over two hundred and fifty alcoholics under his care. Magnan’s research convinced him that those addicted to absinthe suffered far worse and from distinct symptoms than those who drunk pretty much anything else.

(BTW: Other doctors and newspapers criticized Magnan for giving cold comfort to those “afflicted” by this absinthe/alcohol induced degeneration theory and robbing those genetically related to them of all hope of avoiding a similar fate.)

So, of course, Magnan coined a term.

Absinthism, he believed, was characterized by hallucinations, delirium, bouts of amnesia, tremors, sleeplessness, seizures, and violent fits brought on by one of absinthe’s key ingredients — wormwood. A man of science, Magnan sought to prove his absinthism theory by conducting a series of tests. Procuring two guinea pigs, he placed each under their own glass domes. In one enclosure, Magnan placed a saucer of pure alcohol; in the other, he set a saucer of wormwood oil and then watched the animals inhale the vapors. Whilst the guinea pig with alcohol merely grew inebriated, the one exposed to wormwood oil grew highly excited, then collapsed into seizures and died.

You see the problem with his experiment, don’t you? Magnan didn’t use absinthe. He used wormwood oil.

A drawing of what Artemisia Absinthium looks like.

This concentrated form of Artemisia Absinthium owns significantly more thujone (the chemical compound responsible for the animal’s seizures) than the common wormwood plant or absinthe. Hence, Magnan did some spectacularly bad science by performing an experiment guaranteed to prove his theory.

(From the Office of Fairness: It’s unclear if Magnan made this error in good faith, i.e., just an ordinary cockup — or — if he tested absinthe on the animals and switched to wormwood oil when they failed to prove his theory.)

Magnan also didn’t take into account the adulterated versions of absinthe floating around France by this time, either. Unlike wine or brandy, absinthe had no governmental oversight keeping distillers honest. So as absinthe’s popularity grew, unscrupulous manufacturers would contaminate poor quality absinthe or create fraudulent versions by adding things like parsley, turmeric & indigo or copper sulfate to enhance or attain absinthe’s trademark green hue and antimony trichloride to achieve the spirit’s signature ouzo effect. Whilst parsley and turmeric aren’t a problem, the other substances aren’t particularly good for you when ingested and could account for the array of symptoms Magnan attributed to absinthism. Moreover, the people most likely to partake of the polluted versions, the desperately poor and alcoholics who’ve hit rock bottom, were more likely to wind up institutionalized than their wealthier counterparts — thereby skewing Magnan’s theory from the outset.

Flawed as Magnan’s methodology was, he felt confident enough to publish a paper on the perils of absinthe, its chronic use, and absinthism in 1869. (And its flawed conclusions have bedeviled absinthe ever since).

Two paintings depicting the Green Fairy’s influence.

The bohemian artists of France embraced a slice of Magnan’s findings. Loudly extolling the virtues of absinthe’s purported psychedelic properties, they claimed brought a clarity of mind, which in turn enhanced their creativity. Naming absinthe’s muse like qualities the Green Fairy, artists like Manet, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Alfred Jarry, Oscar Wilde, and Vincent Van Gough all sought out absinthe’s warm embrace and some even put her into their works.

(Fun Fact?: Critics of absinthe are forever pointing at the generally early deaths of these aforementioned artists as proof of absinthe’s toxic qualities. However, what these fault finding individuals generally ignore is this group of artists also enjoyed a host of other ailments like syphilis, TB, and mental illnesses which alcohol of any variety would’ve exacerbate.)

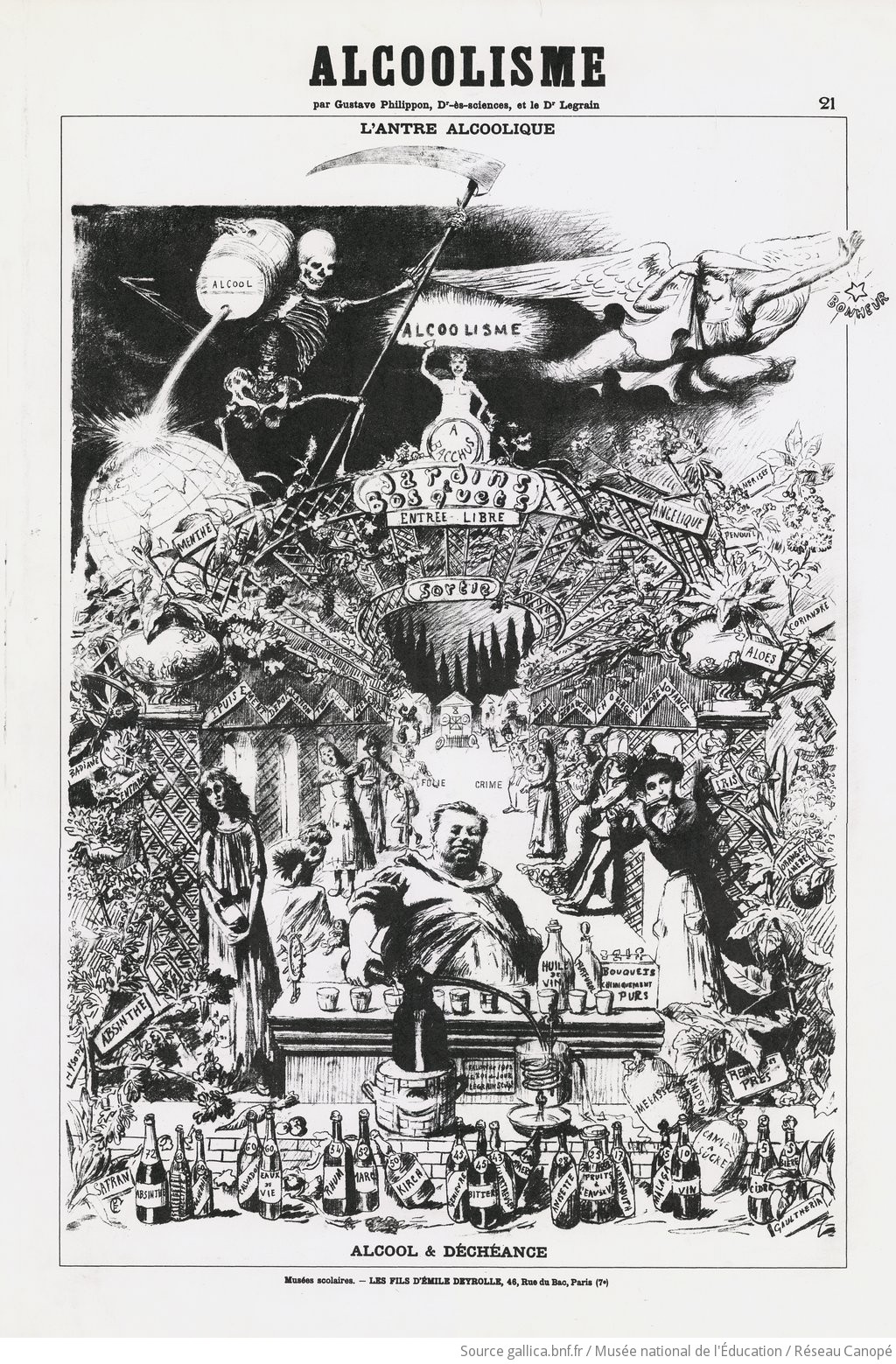

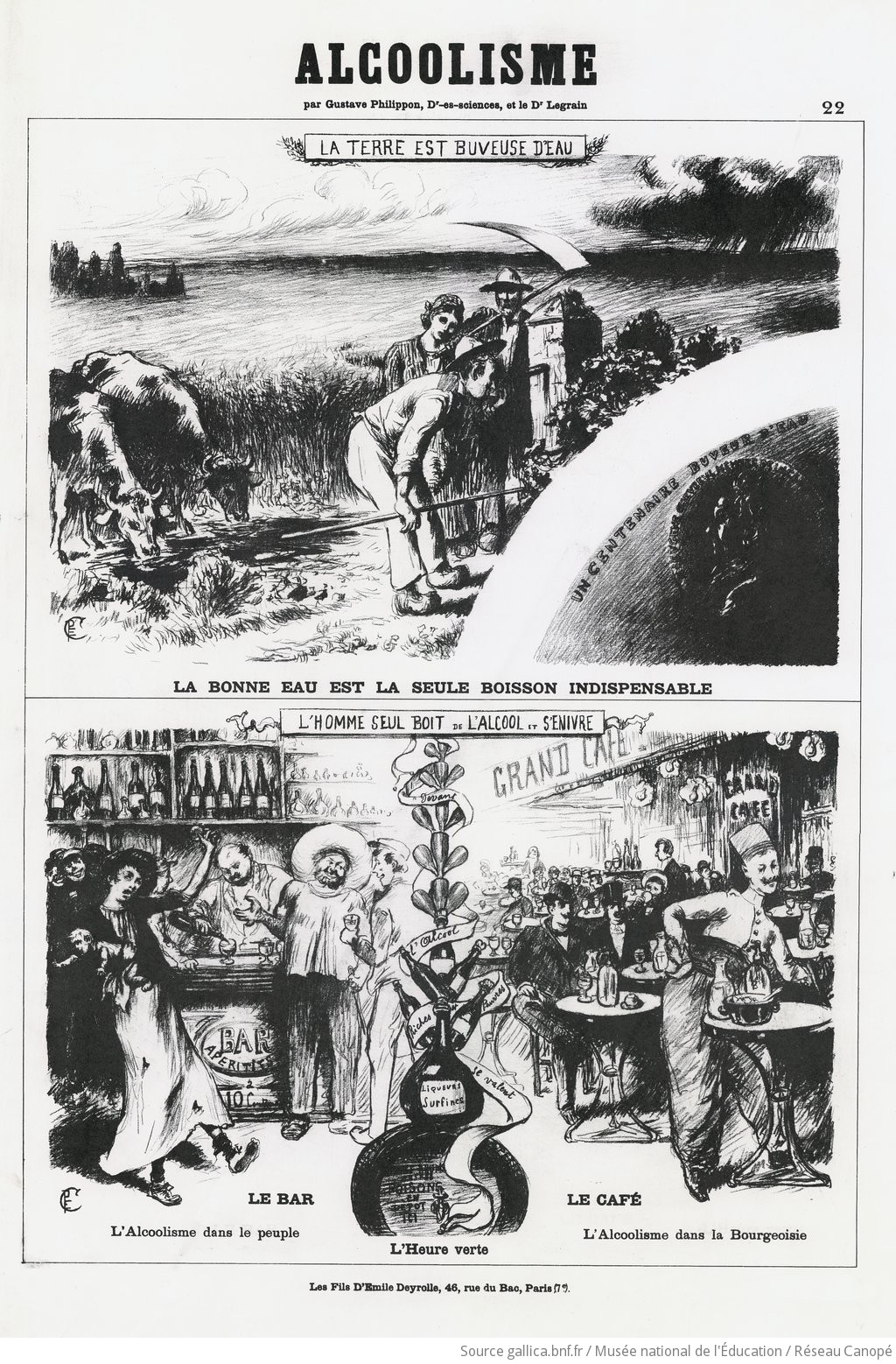

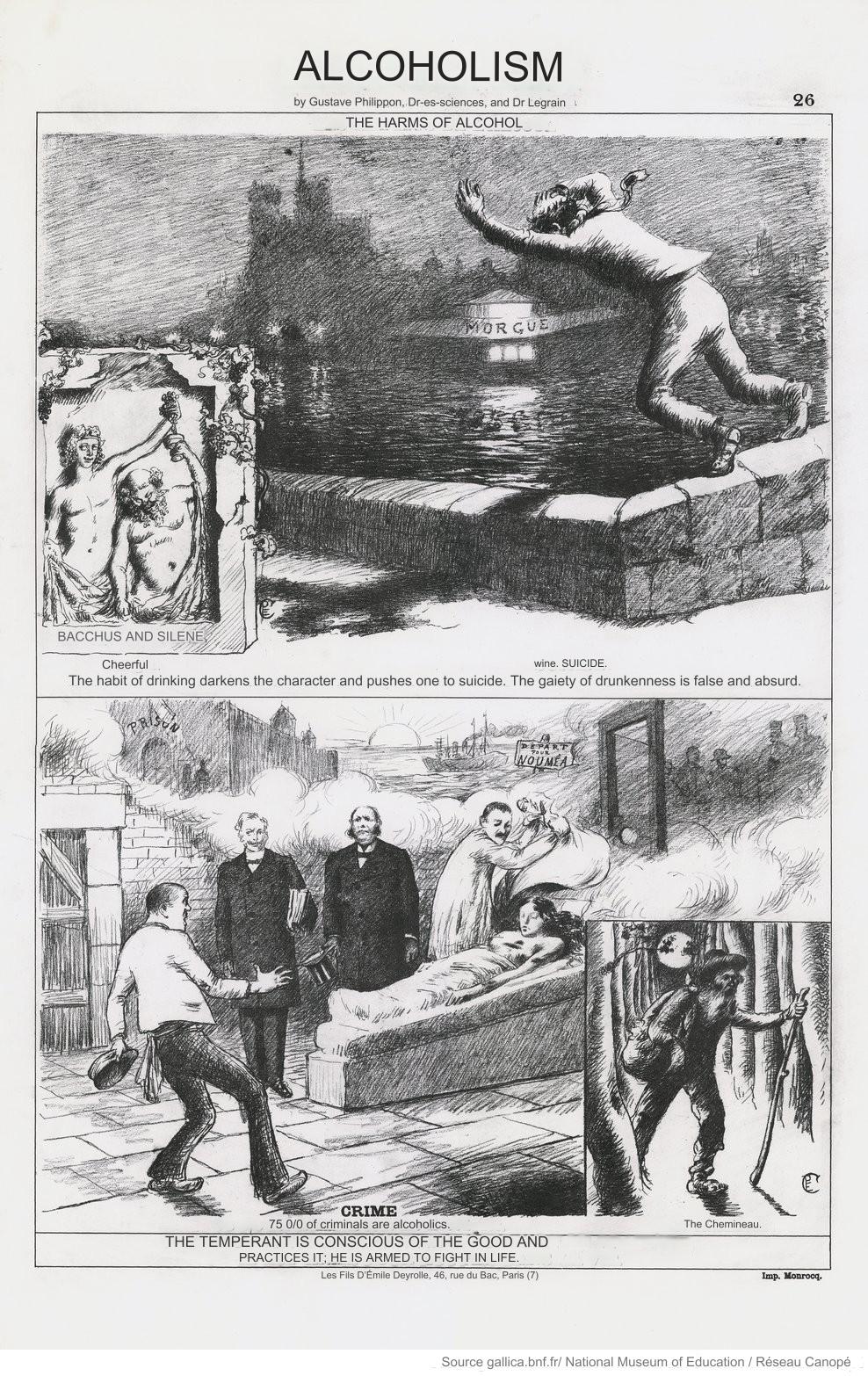

A photo of Dr. Paul Maurice Legrain and some of the propaganda he helped create. (The first three contain absinthe references and the last one is translate.)

In any case, these wholehearted endorsements of absinthe’s spectacular effects cut little ice with the growing conservativeness in France, including a student of Magnan’s, Dr. Paul Maurice Legrain. Like his mentor, Legrain too was a chief physician of an insane asylum, only he specialized in the treatment of alcoholics. While his mentor viewed absinthe as the sole author of France’s decline, Legrain widened this stance, considering alcohol and alcoholism as the root of France’s social evils. However, rather than doing medical research into how to successfully treat the disease, Legrain threw himself into France’s growing temperance movement. In 1897 he founded the French Anti-Alcoholic Union then grew its membership numbers from 40,000 in 1903 to 125,000 in 1914.

At about this point, the late 1890s, French grapevines and vintners had bounced back (which took about thirty years), thanks to grafting and hybridization with louse-resistant American vines….Only to discover they’d a formidable rival. Even worse, a substantial number of drinkers were uninterested in abandoning absinthe’s leisurely glitz & glam or its lower price point. Leaving French wine producers flailing about for ideas on how to rid themselves of this brash green upstart.

Then came the afternoon of August 28, 1905.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024