Did you know there were such structures as rotary jails? Me either!

This short-lived fad in jail design was thought up by William H. Brown and built by Haugh, Ketcham & Co. during the late 1880s. Whilst it’s unclear how many of these rotary jails were actually built (the lowest count being seven, the highest eighteen), only three remain standing today. A one-story version located in Crawfordsville (Indiana), a two-story model in Gallatin (Missouri), and a three-story type in Council Bluffs (Iowa).

Don’t know what they look like? Well, first, toss aside all the images of the inside of Alcatraz and most prison movies you’ve got rattling around inside your head.

Now imagine a Merry-Go-Round.

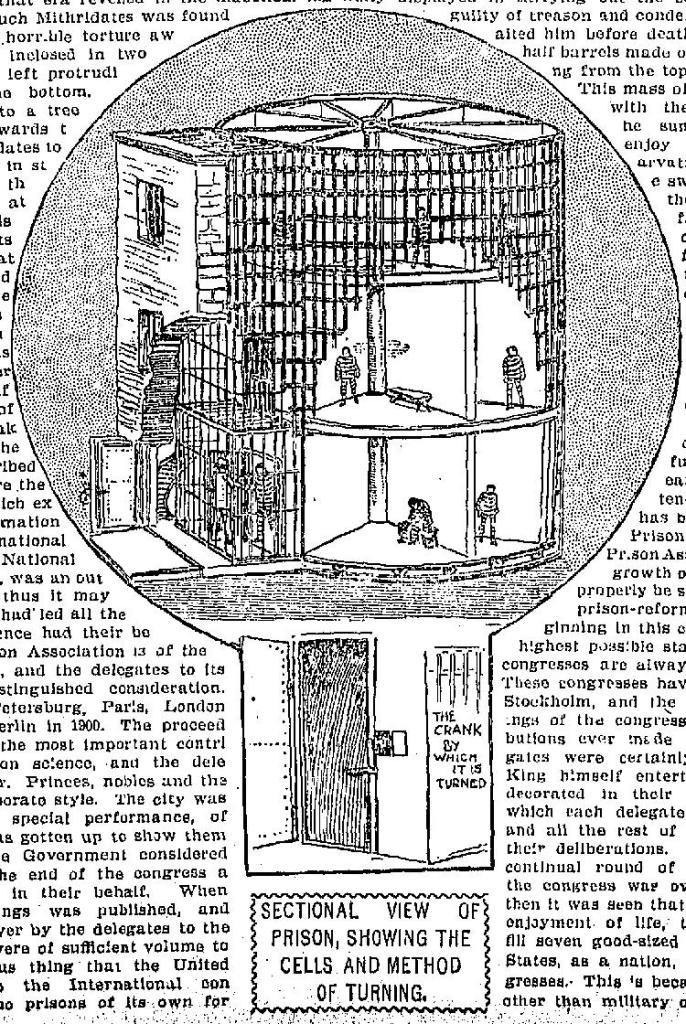

Subtract all the horses, the odd stationary benches, the calliope, mirrors, and fun. Now, divide the bare platform into wedge-shaped rooms with a central shaft in the middle. Enclose the entire equally divided platform in a stationary floor-to-ceiling circular cage that sports a single gap. Finally, plunge beneath the round cell block’s floors into a small room that holds a hand crank. This mechanism allowed a single officer to rotate the platform upon which the cells rested, granting one cell access to the ingress/egress opening at a time.

The rotary jail in Council Bluffs, the largest of the three still standing, has ten cells per platform and can house two men per cell. In its heyday, the Pottawattamie County Jail could hold up to thirty men at a time. (Women had separate “accommodations”.)

And much like the Titanic, whose promoters labeled it unsinkable — rotary jails were touted as escape proof.

You can see where this is going.

The year after it was constructed (1888), the Pottawattamie County Jail saw its first jailbreak, another a couple years later, and yet another in 1902. The first two were accomplished by sawing through the bars across a window in a common area, and in the last, the inmates picked a lock, overcame the warden (and his wife), and scampered out. A different rotary jail saw two men bust through a metal plate next to the toilet in their cell, climb down the central shaft, then escape through an attached root cellar.

Despite the “escape proof-ness” not holding up well against the ingenuity of men with plenty of time on their hands, it did succeed in another of William H. Brown’s design aims — limiting contact between prisoners and jailers. To this end, thanks to the spaciousness of the central shaft, each cell was plumbed for and installed with a toilet. Thereby eliminating one of the most frequent interactions between an inmate and a warden.

Unfortunately, access to your own whizz station was about the only upside for the inmates living within a rotary jail. (Until the plumbing started acting up, which, according to the info I found, happened A LOT.)

While designed with maximum protection for guards in mind, the architect let prisoner safety fall by the wayside. Not only did the placement of the crank below the block of prison cells make it difficult (if not impossible) for someone to operate it in the event of a fire. Thereby rendering this style of jail a death trap for prisoners as well as any jailer trying to rescue them. The crank’s location, together with the noise of the moving platform, also ensured whoever operated it was out of earshot of any screams emanating from above.

I am not kidding.

Apparently, the stationary nature of the cage/bars surrounding the movable cells meant if a prisoner dangled a finger, foot, arm, or other appendage through the motionless bars when the floor started rotating and wasn’t fast enough pulling their limb back within the cell — said extremity would be crushed at best and amputated at worst.

What’s even more grim? Depending on the limb caught in the bars, it could cause the mechanism to seize up until removed. Leaving a prisoner with a horrific injury and unable to receive medical attention.

Speaking of the rotation mechanism, it’s what signed the death warrant on William H. Brown’s design. As every single one failed within the first few years of being constructed. Despite extensive remodeling and retrofitting (which usually saw the mechanism permanently disabled and the addition of doors to every cell), all the rotary jails were condemned by 1939.

Save for Pottawattamie County Jail.

A pic of the jail in Council Bluffs from the Des Moines Register in 1972.

Its rotation mechanism limped along until the mid-nineteen-sixties, when it too was sabotaged by city employees after the jailers were unable to retrieve an inmate’s corpse for two days after he passed away of natural causes in his cell. Despite overcoming this nightmarish event and the twenty-two other times one official or another condemned it — the last working rotary jail in the country was finally closed in December 1969…..

…..And in steps Elizabeth Dean, the mystery writer behind Murder is a Collector’s Item. An avid and active member in the Historical Society of Pottawattamie County, Elizabeth helped convince town officials the “Squirrel County Jail” (as it was known by the locals) would be a good tourist draw due to its uniqueness.

After she (and others) saved it from the wrecking ball, Elizabeth converted the jail’s pantry into an exhibit area and added some of her own antiques to fill out the display. Elizabeth then ensured its popularity by booking tours and selling tickets!

My 52 weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024