Genevieve Forbes did some great writing, but when it came to Isabella? To put it nicely, which is more than she did for Isabella, Genevieve was a sourpuss (as my grandmother would say).

In early July 1923, Isabella Nitti-Crudelle and Peter Crudelle went on trial — pleading not guilty. Whereupon, Isabella drew some singularly harsh criticism from Genevieve Forbes, a prominent female reporter who covered the crime beat for the Chicago Tribune.

Forbes took exception to basically everything about Isabella, calling her: “…dumb, crouching, animal-like Italian peasant” and “…dirty, disheveled woman…” amongst other derogatory terms. Other reporters picked up this language, calling Isabella: “Dumpy and squat and with no redeeming gift of grace, the dumb-like little peasant woman….creature of primitive physical instincts…mussy twisted hair and swarthy brow so seamed and crinkled with premature marks of age….leathery face and warped figure…”

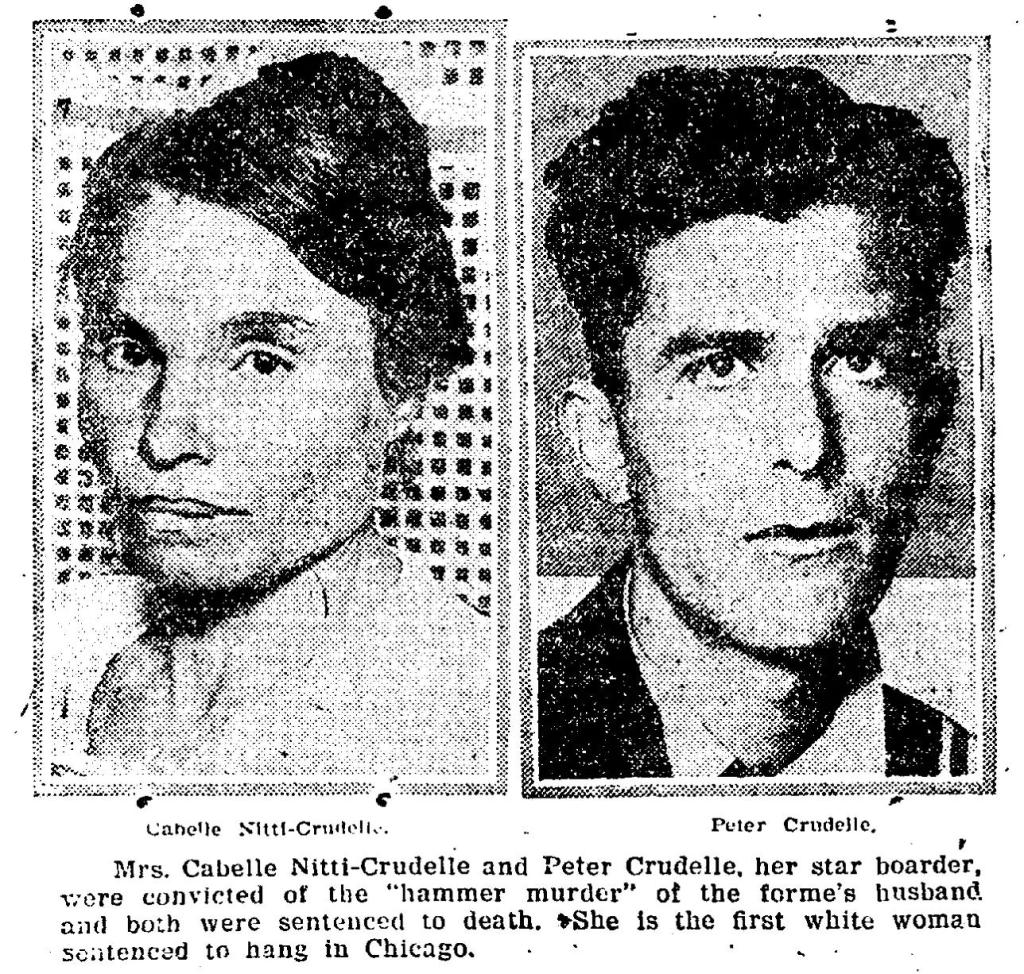

A couple of the unflattering photos & drawings of Isabella used by a NUMBER of papers – and – a blurb “explaining” why the jury ruled the way they did.

These dehumanizing descriptions go on and on and on.

By referring to Isabella in such terms, Forbes and the others of her ilk painted Isabella as subhuman and undeserving of compassion, sympathy, or mercy from their readers or the jury. Moreover, by focusing on Isabella’s southern Italian heritage, language, and mannerisms — Forbes tapped into the anti-immigrant sentiment of the day (as exemplified by the Immigration Act of 1924, crafted by a fan of eugenics and a man who thought the US needed a Mussolini type leader to pull the country out of the Great Depression). Which only increased Isabella’s status as unworthy of the leniency shown to the bevy of other accused murderesses who’d come before her.

Unsurprisingly, Isabella and Peter (who’d practically become a footnote in the newspaper coverage of the crime) were convicted of Frank’s murder and sentenced to hang on October 12, 1923. A punishment that caused a sensation across the country, as Isabella was only the fourth woman ever to receive a death sentence in Illinois.

While most believed Illinois’s Governor Len Small would commute Isabella’s death sentence to life in prison, which had been done for the two other women before Isabella — it wasn’t a sure thing. In 1845, Illinois’s Governor Thomas Ford failed to intervene on behalf of Elizabeth Reed, who’d hung after being convicted of poisoning her husband. Above and beyond Illinois’s single female execution seventy-eight years earlier, there’d been an uptick around the world of female death sentences being carried out: Dora Wright (1903 Oklahoma), Mary Rogers (1905 Vermont), Mary Farmer (1909 New York), Virginia Christian (1912 Virginia), Pattie Perdue (1922 Mississippi), and, across the pond in England, another cause célèbre murder case resulted in the hanging of Edith Thompson on January 9, 1923.

Even more worrisome, Isabella’s conviction failed to stem the flow of dehumanizing remarks. Many of the reports after Isabella’s date with the hangman was announced made it sound as if Isabella was grateful for her confinement on Murderess Row: “….she seems thankful for the better jail fare with occasional time for play, recreation, and with no worry now for poverty nor endurance of bitter cold.” Whether these comments were meant to assuage the public’s guilt over the state’s mandate of death or to make her execution sound akin to mercy is unclear. What we do know is Isabella was terrified. Alongside these reports of Isabella’s “gratefulness” were stories of her enduring panic attacks, obsessive cleaning & singing (undoubtedly done to try to keep her mind occupied), and at least two suicide attempts.

Thankfully, not everyone shared Genevieve Forbes’s point of view.

After the death sentence was handed down, one juror’s wife threatened to leave him if Isabella hanged. Another group of women bent on obtaining Isabella’s freedom took Forbes to task for her attacks on Isabella’s appearance and character. Unsurprisingly, Forbes mocked their rebuke in print and labeled their efforts to free Isabella as: “…women’s primitive loyalty to a forlorn sister, down and out, and homely.”

Crucially, besides gaining the sympathy of women around the city and the support of those opposed to the death penalty under any circumstance — Forbes’s inhuman rhetoric and reports of the trial itself inspired five Italian American lawyers (Swanson, De Stefano, Bonilli, Mirabella, and Helen Cirese) to step in and take Isabella’s (and Peter’s) appeal on pro bono.

First, the legal team took aim at the circumstantial evidence used to convict: Identification of the body — which rested on a single ring, the inconsistencies between Charles Nitti’s confession and the state’s evidence (where he said the body was dumped in a river, yet the body identified as Frank’s was found in a catch basin), and the fact there was another suspect with plenty of motive whose identity was deemed inadmissible during the trial.

However, the main thrust of the quintet of lawyers’ appeal rested on the absolutely abysmal defense mounted by Isabella and Peter’s former trial lawyer, Eugene A. Moran who, the Illinois Supreme Court would later say, “….It is quite clear from an examination of the record that the defendants’ interest would have been much better served with no counsel at all than with the one they had.”

For example: Despite securing a translator who spoke Barese, the Italian dialect Isabella spoke, Moran exchanged very few words with her prior to stepping into the courtroom — so how could she aid in her own defense? Moreover, during Moran’s cross-examination of Isabella and Peter, he repeatedly asked them questions that could’ve led them to incriminate themselves on the stand. Apparently, it got so bad that at one point, the trial judge stepped in, warning Moran he was harming his client’s defense. (A caution which didn’t alter Moran’s behavior a whit.)

(BTW: Before we paint Moran in villainous colors, according to a couple of recent articles/blog posts, he’d started suffering from some sort of mental health problems around this time. Which could account for this subpar court performance. Though I’ve been unable to verify this information, I thought it worth mentioning.)

Taking all these legal points under consideration, on September 26, 1923, Justice Orrin N. Carr stayed Isabella and Peter’s execution until their appeal could be presented to the Illinois Supreme Court in February 1924.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

This Week’s Recipe: Blueberry Hand Pies

I love a handpie. Even better? Recently, I learned how to make pie dough via a food processor, which utterly changed and simultaneously upped my pie game! Turns out, I wasn’t adding enough water and my hands were entirely too warm to work with such a temperature-sensitive mixture, hence, why the food processor was such a game changer.

So when I found this recipe for blueberry hand pies, I was excited to try it! Even better? They turned out beautifully the very first time.

The reason my pies are circular rather than square is on account of my kitchen’s lack of a pastry wheel and a reluctance to cut my silicone baking mat to ribbons made me avoid using a knife or a pizza cutter. Then I recalled purchasing, forever and a day ago, a pastry cutter (think cookie cutter but bigger) the approximate size called for in the recipe.

(And because I’m me, I also added a pinch of cinnamon to the filling.)

Agatha Christie: I can see Captain Hasting sinking his teeth happily into one of these pies on a summer’s day during a picnic he arranged with one lady or another!

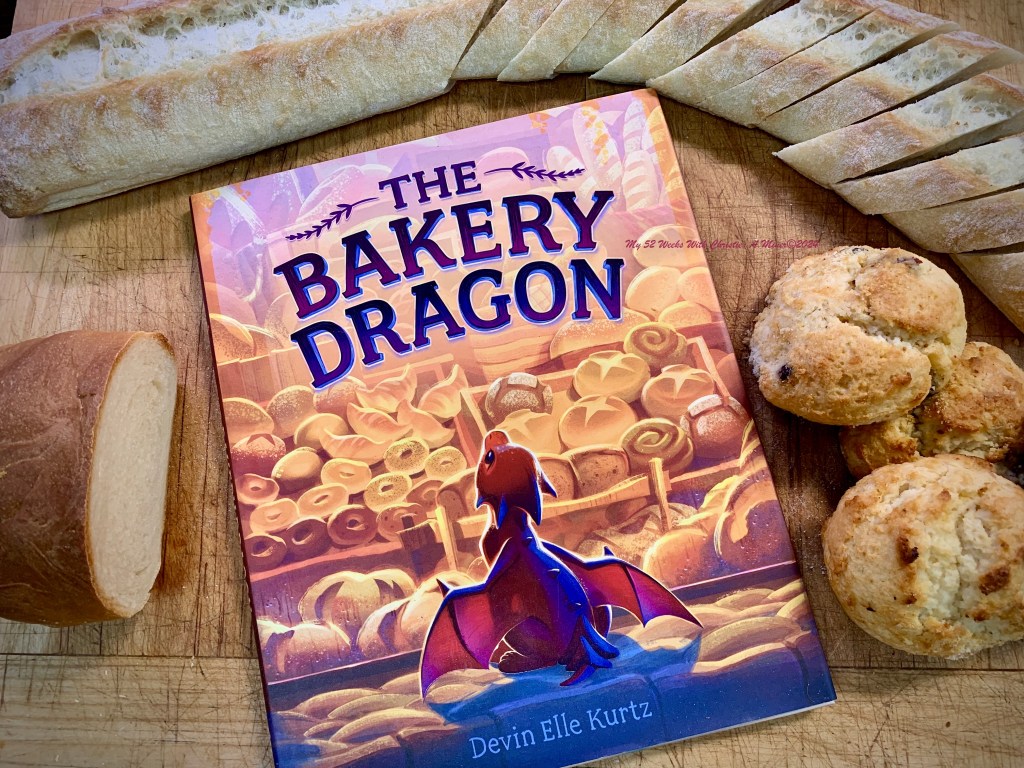

Okay, so I am not exactly the target audience for this….this picture book.

There, I said it. I bought myself a picture book.

But how could I not?

After seeing the magnificent art Devin Elle Kurtz posted on Tumblr about a little dragon in a bakery, I couldn’t resist.

And The Bakery Dragon didn’t disappoint.

(I mean, just look at the art on the dust jacket and cover!)

Not only are the drawings wonderfully rendered, but the story itself does an excellent job of showing how to be kind, forgiving, and sharing without becoming a stilted ‘message’ story. (A particular pet peeve of mine in children’s literature from my time as a bookseller.)

In any case, for those of you looking for a superb kid’s book (for ages 4-8, or for those who love a good book regardless of its intended audience) this holiday season, I highly recommend The Bakery Dragon!

Admittedly, unlike the painting in Agatha Christie’s short story The Bloodstained Pavement, which tangentially helped solve a murder, the Trumbull portrait clearly caused one. Nor did the Chicago police need Miss Marple’s hard-won acumen to solve Paul F. Volland’s murder. Yet there’s one question I still haven’t found a definitive answer to: Did Vera Trepagnier’s looks play a substantial role in her conviction?

In a similar vein to “Can A Beauty Be Convicted?” — this headline pits the three most “beautiful” murderesses in Chicago against Mrs. Malm and Mrs. Nitti-Crudelle who were judged as sullen, ugly, and “animal like” by newspapers of the day.

According to the 1923 headline, “Can A Beauty Be Convicted?” which featured a photo of Vera amongst others below the headline, it did. Yet, as I (hopefully) showed in the previous posts, Vera’s conviction owed little to her looks and more to her own behavior, together with her lawyer’s failure to address the unique features of her crime in their efforts to shim her case down to fit the Murderess Acquittal Formula. More importantly, Vera herself never mentioned this line of reasoning (at least in the articles I read) in the interviews given after her conviction. Nor did the papers harp on about her features during her trial, focusing instead on her “gentle spiral” into poverty and the prominence of the late Paul F. Volland.

But what of the other handful of convicted murderesses during this period? Did their looks play a role?

Hilda Exlund, a Swedish immigrant, certainly thought so: “If I had been young and pretty I suppose I’d have been turned loose just as the other women who have been tried for killing their husbands.” In fairness, Hilda’s lack of good looks did draw comment by the press. However, they weren’t harped on in any of the stories I read. Moreover, prior to her conviction, Hilda drew very little attention from Cook County’s press core. Meaning their news articles neither helped soften the potential jury pool leading up to the trial nor hurt Hilda’s chances for an acquittal. To my mind, what actually foiled Hilda’s acquittal prospects lay in the same realm as what sunk Vera Trepagnier’s bid for freedom seven months(ish) later.

The only pic I could locate of Mrs. Exlund

According to Hilda: On the evening of October 16, 1918, whilst standing in the kitchen chopping a cabbage up for dinner, her husband Frank attacked her. In the ensuing struggle over the butcher knife, Hilda stabbed Frank repeatedly and killed him.

A clear case of self-defense, right?

The hitch in the giddy-up here was, after speaking with friends and neighbors, police quickly uncovered a pattern of violence within the Exlund household perpetrated not by Frank against his wife — but by Hilda against her husband. According to their acquaintances and next-door neighbors, Hilda routinely abused her husband: Some spoke of Hilda’s habit of belittling, cursing, and beating Frank. Another relayed an episode where Hilda poured a pot of boiling hot water over Frank. Others spoke of an incident occurring a few weeks before his death, when Frank beat feet from his house while holding a bloodied handkerchief to his face, whereupon he told multiple people, “She tried to kill me.” Tallied together, these stories painted Hilda as the aggressor while reframing Frank’s possible motivation for striking first. More importantly — they negated Hilda’s claim to the “unwritten law.”

During the ensuing trial in January 1919, Assistant State’s Attorney Edward Prindiville drew the jury’s attention to Hilda’s form by highlighting the disparity between Hilda’s “powerful physique” and her husband’s slim frame. Thus validating Hilda’s belief her looks played a role in her murder conviction and subsequent sentence of 14 years inside Joliet Prison — though not quite in the way the headline above insinuates. All that being said, the fact Hilda’s jury was comprised exclusively of married men or the fact she was tried in Judge Windes’ court (who presided over two other successfully prosecuted cases we’ll explore later) could’ve influenced the outcome as well.

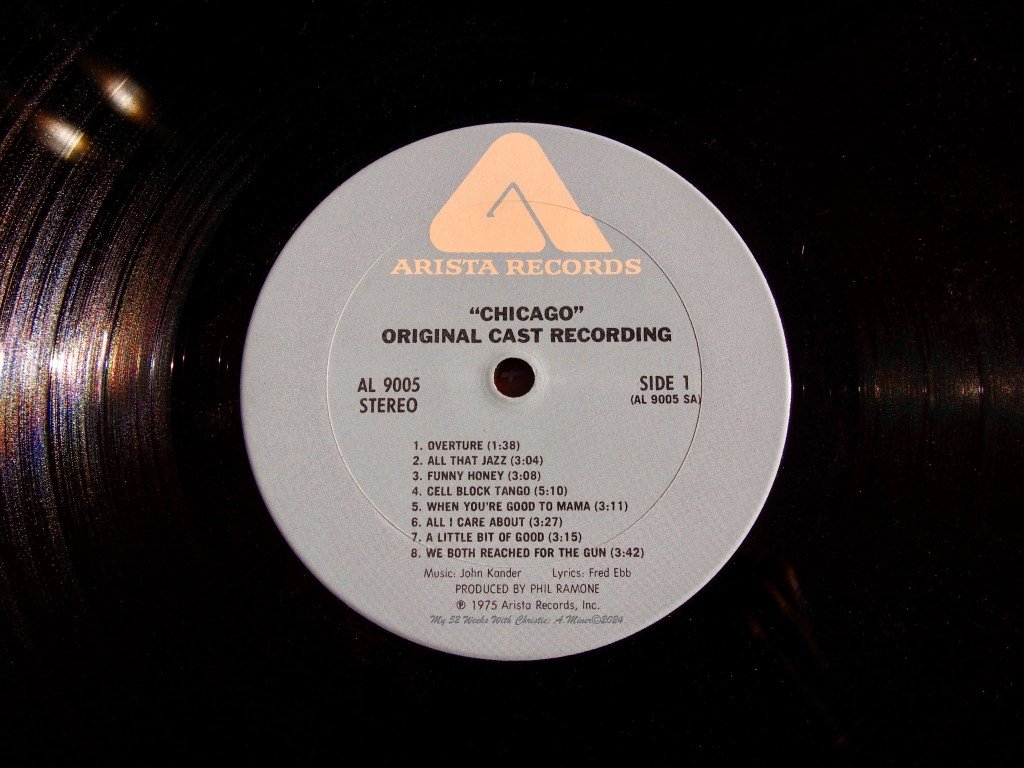

Weirdly, while studying Hilda’s crime — Chicago’s ‘Cell Block Tango’ kept echoing through my brain. Specifically, June’s portion of the song designated ‘Squish’, where she describes how her husband “ran into her knife ten times” during a fight that kicked off while she was “carving a chicken for dinner”. I do not know if Hilda inspired the third member of the “six merry murderesses” — but I do know who provided the inspiration for Katalin ‘Hunyak’ Helinszki. The Hungarian woman who sang the fourth refrain, ‘Uh-Uh’ during the aforementioned song and was hung later on in the musical.

Her name was Isabella Nitti Crudelle* — and her looks alternately condemned and saved her from a trip to the scaffold.

Isabella’s ordeal began on July 29, 1922, when her husband, Frank Nitti, disappeared from their farm. Unsurprisingly, Isabella, with the aid of one of her sons, as she knew very little English at this point, reported him missing the next day. During the subsequent investigation, Isabella’s sixteen year old son Charles confessed to helping, under duress, Peter Crudelle (the Nitti’s farmhand/boarder) dispose of his father’s body in the Des Plaines River. After witnessing Isabella pinning down Frank’s hands while Peter repeatedly struck him in the head with a hammer while Frank slept under a cart. Unfortunately for the police, they had zero luck locating Frank’s corpse downriver, and without a body, the indictment against the pair was dismissed.

Endeavoring to break the case, in late September 1922, the police arrested and charged Peter and Isabella for adultery. However, whatever confession they’d hoped to extract from the couple failed to materialize and they were released. The couple would marry soon(ish) after, thus thwarting a repeat of this particular stratagem.

Fast forward to May 9, 1923: When a body was discovered in a nearby catch basin. James Nitti positively identified it as that of his brother Frank — based on a ring found on (or near, I’m not quite sure) the body. And despite Charles’s story not quite aligning (i.e., the body being found in a catch basin instead of on the banks of the Des Plaines River), the prosecutors decided to charge Peter with first-degree murder and Isabella as an accessory before and after the fact. Initially, Isabella’s son Charles was charged as an accessory after the fact, but turned state’s evidence to get out of trouble.

*I’m using Isabelle versus Sabella (the nickname used in the newspapers of the time), as it’s the name used on her headstone and two notes I’ve seen where she signed her name.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

This Week’s Recipe: Protein Pancake Bites

In a quest to use up a whole mess of blueberries whilst on the lookout for new breakfast/snack ideas, I came across this intriguing recipe. Opting, obviously, for the blueberry version, I set to work.

And they turned out….okay. They were perfectly edible, but flavor wise? I found them a touch boring.

Not willing to let this pancake bite idea go and more than willing to futz with a recipe, I made a second batch. Only this time, I added the zest of one lemon, a teaspoon of vanilla, and a teaspoon of cinnamon to the base batter…Which bumped up the flavor nicely.

Agatha Christie: I can totally see Miss Marple messing around with a recipe until it’s exactly how she wants it, too! Though I’m not sure she’d ever make pancake bites.

Can’t Spell Treason Without Tea — Rebecca Thorne

If one chucked a Harlequin Romance novel, a D&D campaign, tasty pastries, and gallons of tea into a cauldron — you might end up with Can’t Spell Treason Without Tea.

Initially, the story is about Reyna, a private royal guard, who’s fed up with serving the world’s worst boss — aka the Queen. The problem is quitting isn’t exactly an option, as she thoroughly enjoys having her head attached to her shoulders.

But sometimes, you just can’t take it anymore.

Running away into the mountains Renya, with all-powerful mage girlfriend Kianthe by her side (well, actually flying her griffon), the pair open a bookshop/teahouse/bakery in a small mountain hamlet on the cusp of dragon country.

And this is where the mystery starts.

For you see, the dragons are pissed. Someone stole a clutch of their eggs and they want them back….And Kianthe gets tasked/cursed/bespelled (depending on your view) to locate and return them.

I really enjoyed reading this book and cannot wait until the second book in the Tomes & Tea series arrives at my house later today! Perhaps not what people would snobbily call “high fantasy”. Can’t Spell Treason Without Tea is fun, funny, entertaining, and intriguing. Basically, everything I’m looking for in a book, especially during the cozy autumn season.

I would recommend this book to anyone looking for a light fantasy novel with snarky humor, action, magic, and dragons.

BTW: Whilst the book has a punny title, don’t let that fool you. The Tomes & Tea are the background setting for the main plot, not the plot itself. So they never distract from what our two heroines are trying to accomplish.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

The Paul F. Volland Company published some Raggedy Ann stories, as well as, the New Adventures of “Alice” based on Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

Let’s be clear: I believe Paul F. Volland pulled a bait-and-switch on Vera Trepagnier. I think he used his position as President of the P. F. Volland Company, his business acumen, and knowledge of Vera’s strained circumstances to his advantage in order to obtain and keep the Trumbull portrait of George Washington. By dangling the promise of $5,000 before Vera, Volland gained possession of the painting. Next, by carefully wording the contract, he — not his company — secured ownership of the diminutive object if sales of the reproduction reached the 5k mark. If said sales didn’t pan out, which he was in the perfect position to ensure, Volland could point at the $500 advance and issue an ultimatum — either accept it as payment or repay the shortfall in a lump sum. Secure in the knowledge she couldn’t.

The fact he didn’t maintain contact with Vera, nor had his lawyers issue said ultimatum until Vera made it patently clear she would continue to pester him for forever and a day, is why I’m inclined to view his actions under a crooked light. Because without that $5,000 promise, I don’t think Volland could’ve pried that painting out of Vera’s hands. (And I don’t see him giving Vera $500 as a charitable act.)

Examples of the fancy postcards printed by the P.F. Volland Company.

The question is, why would a wealthy man bilk a widow? The only concrete reason I found that might, and I mean might, explain such behavior occurred a few years before Volland’s death: When he nearly declared bankruptcy. Ultimately, Volland didn’t. But perhaps after skating so close to financial ruin, it invoked an unscrupulous or miserly side to his nature? Or maybe he grew up unable to rub two nickels together, which left him unwilling to pay a penny more for anything when he didn’t have to. Or perhaps he was just crafty.

It’s unclear.

Interestingly, Vera’s charge of sharp business practices against Volland wasn’t the only one I found. A female musician contracted to write some sheet music for the P. F. Volland Company claimed that after Volland rejected her song, he later published it under someone else’s name without her permission or paying her for the work. What’s more, the day after Volland’s death, Chicago artists announced their intention to raise funds for Vera’s defense…..Again, this makes me wonder how fair Volland played with others when wheeling and dealing.

Unfortunately for Vera, partaking in dodgy business practices doesn’t automatically translate into owning a violent streak. (Nor does it mean he deserved to die.)

Other than stating she used a revolver, I’ve no clue the type of firearm Vera used, so here’s a gun advert from 1913. (And yes I know this is not an ad for a revolver.)

This begs the question: Why did Vera feel the need to bring a gun with her to discuss a dispute over a contract? According to the woman herself, “I took the revolver along to scare him. I had no intention of killing him, but that was done when he tried to take the weapon away from me.” An explanation I find believable. What I find harder to swallow is Vera’s claim the one and only day she packed the piece in her purse was the afternoon she accidentally shot Volland.

As I see it, either the stars aligned and allowed Vera to seize an unexpected opportunity to lie her way into Volland’s presence — OR — Vera stalked Volland long enough to know he’d be in his office that particular day. If Vera relied on the ‘universe’ to provide her with an opportunity to enact her desperate plan, then it stands to reason she’d bring the gun along with her daily. Otherwise, how would she have it on hand precisely when she needed it? The latter stalking explanation, which Vera admitted doing, is the only way I see the ‘I only brought the gun with me once’ course of events as plausible. The problem there is it smacks of premeditation.

Either way, neither version of events paints Vera in glory.

More importantly, by bringing the firearm with her, Vera cast herself into the role of instigator, severely undermining any claim of self-defense, crime of passion, or the ‘unwritten law.’ The prosecution weakened Vera’s claim further when they labeled her a blackmailer, presenting at least one nasty letter Vera wrote threatening to ruin Volland’s reputation by exposing his manipulative business practices — lest he make good on their deal.

Without any other testimony (from, for instance, another firearms expert to refute the prosecution’s, a psychiatrist willing to declare Vera mentally unsound at the time of the murder, or anyone who could attest to Vera’s erratic behavior) to mitigate the prosecution’s arguments, Vera’s lawyers only managed to convince one juror out of twelve to find Vera not-guilty. (And he changed his mind by the second ballot.)

Hence why, I feel Vera’s lawyers did her a disservice.

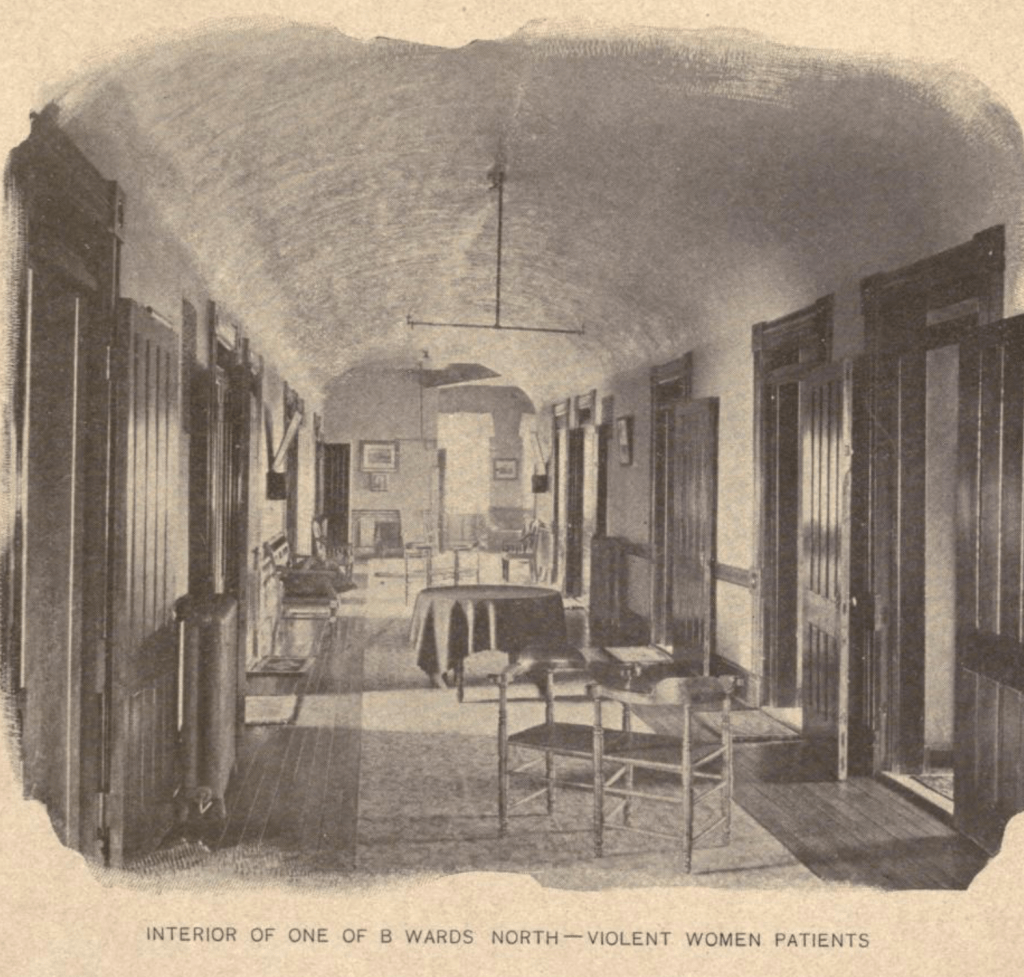

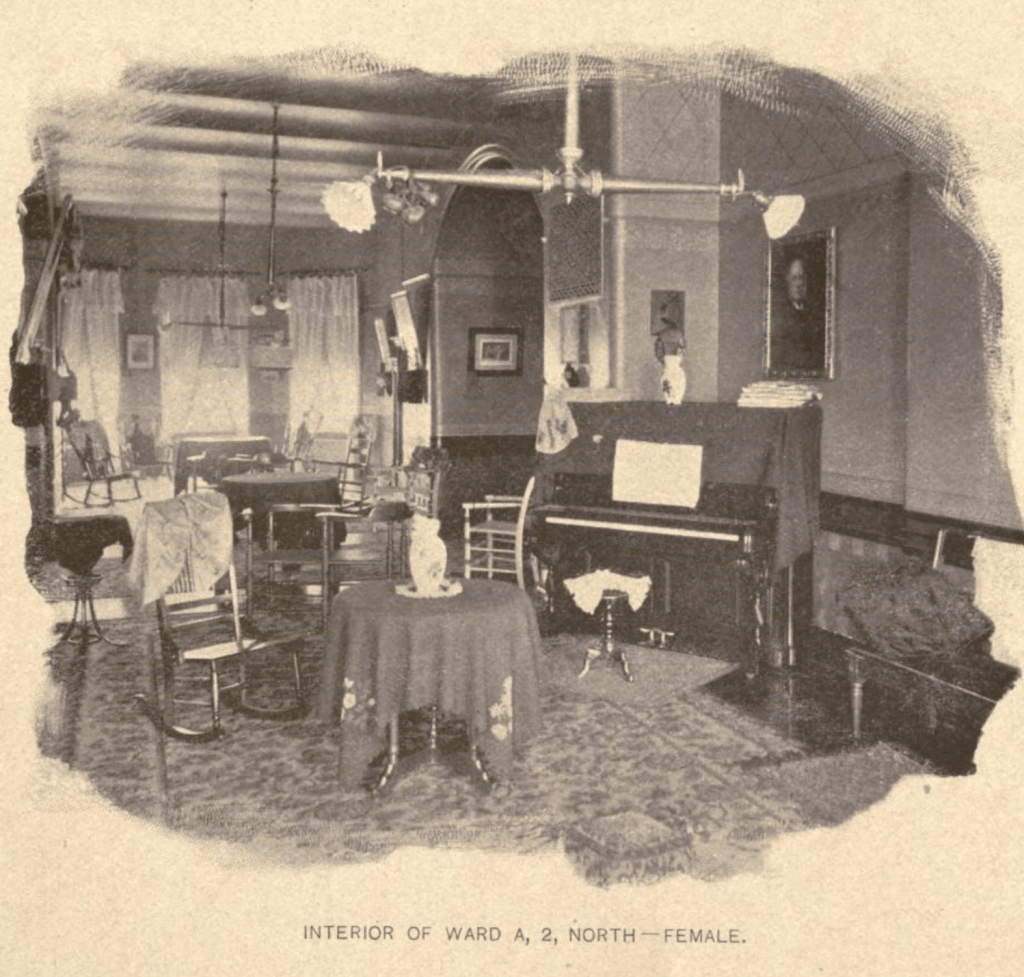

Interior photos of the women’s spaced at Kankakee State Hospital from sometime around 1900.

What happened after the guilty verdict? After Vera’s appeal for a new trial was denied in August 1919, she was transferred to Joliet State Prison to serve her sentence of one year to life. Sadly, at some point after September 1, 1920, Vera was transferred to Kankakee Insane Asylum. According to prison officials, the loss of the Trumbull’s portrait of George Washington (and probably the stress of the trial and incarceration) “unhinged” her mind — causing Vera to speak dreamily of nothing but her former prized possession to anyone willing to listen.

Vera would die within the asylum walls on August 19, 1921.

In her will, Vera left several tracts of land in Maryland, a vase, and the Trumbull miniature to her grandson. Sadly, Vera forgot the vase had already been donated to a museum in New Orleans, so it wasn’t hers to give. And Vera’s only son sold the tracts of land to cover an overdue mortgage.

As for the Trumbull miniature, an attorney by the name of Michael F. Looby was assigned by a probate court to sell it — which made quite a splash in the papers. Assured by art experts, museums, and collectors that ‘Exhibit A’ would fetch anywhere between $5,000 and $30,000, it went to auction. On September 23, 1922, Looby returned to Judge Horner’s courtroom and reported that due to the unpleasant notoriety attached to the painting, the highest bid received was $325.

Whereupon Judge Horner approved the sale — to persons unknown and it disappeared from public view.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.