Admittedly, unlike the painting in Agatha Christie’s short story The Bloodstained Pavement, which tangentially helped solve a murder, the Trumbull portrait clearly caused one. Nor did the Chicago police need Miss Marple’s hard-won acumen to solve Paul F. Volland’s murder. Yet there’s one question I still haven’t found a definitive answer to: Did Vera Trepagnier’s looks play a substantial role in her conviction?

In a similar vein to “Can A Beauty Be Convicted?” — this headline pits the three most “beautiful” murderesses in Chicago against Mrs. Malm and Mrs. Nitti-Crudelle who were judged as sullen, ugly, and “animal like” by newspapers of the day.

According to the 1923 headline, “Can A Beauty Be Convicted?” which featured a photo of Vera amongst others below the headline, it did. Yet, as I (hopefully) showed in the previous posts, Vera’s conviction owed little to her looks and more to her own behavior, together with her lawyer’s failure to address the unique features of her crime in their efforts to shim her case down to fit the Murderess Acquittal Formula. More importantly, Vera herself never mentioned this line of reasoning (at least in the articles I read) in the interviews given after her conviction. Nor did the papers harp on about her features during her trial, focusing instead on her “gentle spiral” into poverty and the prominence of the late Paul F. Volland.

But what of the other handful of convicted murderesses during this period? Did their looks play a role?

Hilda Exlund, a Swedish immigrant, certainly thought so: “If I had been young and pretty I suppose I’d have been turned loose just as the other women who have been tried for killing their husbands.” In fairness, Hilda’s lack of good looks did draw comment by the press. However, they weren’t harped on in any of the stories I read. Moreover, prior to her conviction, Hilda drew very little attention from Cook County’s press core. Meaning their news articles neither helped soften the potential jury pool leading up to the trial nor hurt Hilda’s chances for an acquittal. To my mind, what actually foiled Hilda’s acquittal prospects lay in the same realm as what sunk Vera Trepagnier’s bid for freedom seven months(ish) later.

The only pic I could locate of Mrs. Exlund

According to Hilda: On the evening of October 16, 1918, whilst standing in the kitchen chopping a cabbage up for dinner, her husband Frank attacked her. In the ensuing struggle over the butcher knife, Hilda stabbed Frank repeatedly and killed him.

A clear case of self-defense, right?

The hitch in the giddy-up here was, after speaking with friends and neighbors, police quickly uncovered a pattern of violence within the Exlund household perpetrated not by Frank against his wife — but by Hilda against her husband. According to their acquaintances and next-door neighbors, Hilda routinely abused her husband: Some spoke of Hilda’s habit of belittling, cursing, and beating Frank. Another relayed an episode where Hilda poured a pot of boiling hot water over Frank. Others spoke of an incident occurring a few weeks before his death, when Frank beat feet from his house while holding a bloodied handkerchief to his face, whereupon he told multiple people, “She tried to kill me.” Tallied together, these stories painted Hilda as the aggressor while reframing Frank’s possible motivation for striking first. More importantly — they negated Hilda’s claim to the “unwritten law.”

During the ensuing trial in January 1919, Assistant State’s Attorney Edward Prindiville drew the jury’s attention to Hilda’s form by highlighting the disparity between Hilda’s “powerful physique” and her husband’s slim frame. Thus validating Hilda’s belief her looks played a role in her murder conviction and subsequent sentence of 14 years inside Joliet Prison — though not quite in the way the headline above insinuates. All that being said, the fact Hilda’s jury was comprised exclusively of married men or the fact she was tried in Judge Windes’ court (who presided over two other successfully prosecuted cases we’ll explore later) could’ve influenced the outcome as well.

Weirdly, while studying Hilda’s crime — Chicago’s ‘Cell Block Tango’ kept echoing through my brain. Specifically, June’s portion of the song designated ‘Squish’, where she describes how her husband “ran into her knife ten times” during a fight that kicked off while she was “carving a chicken for dinner”. I do not know if Hilda inspired the third member of the “six merry murderesses” — but I do know who provided the inspiration for Katalin ‘Hunyak’ Helinszki. The Hungarian woman who sang the fourth refrain, ‘Uh-Uh’ during the aforementioned song and was hung later on in the musical.

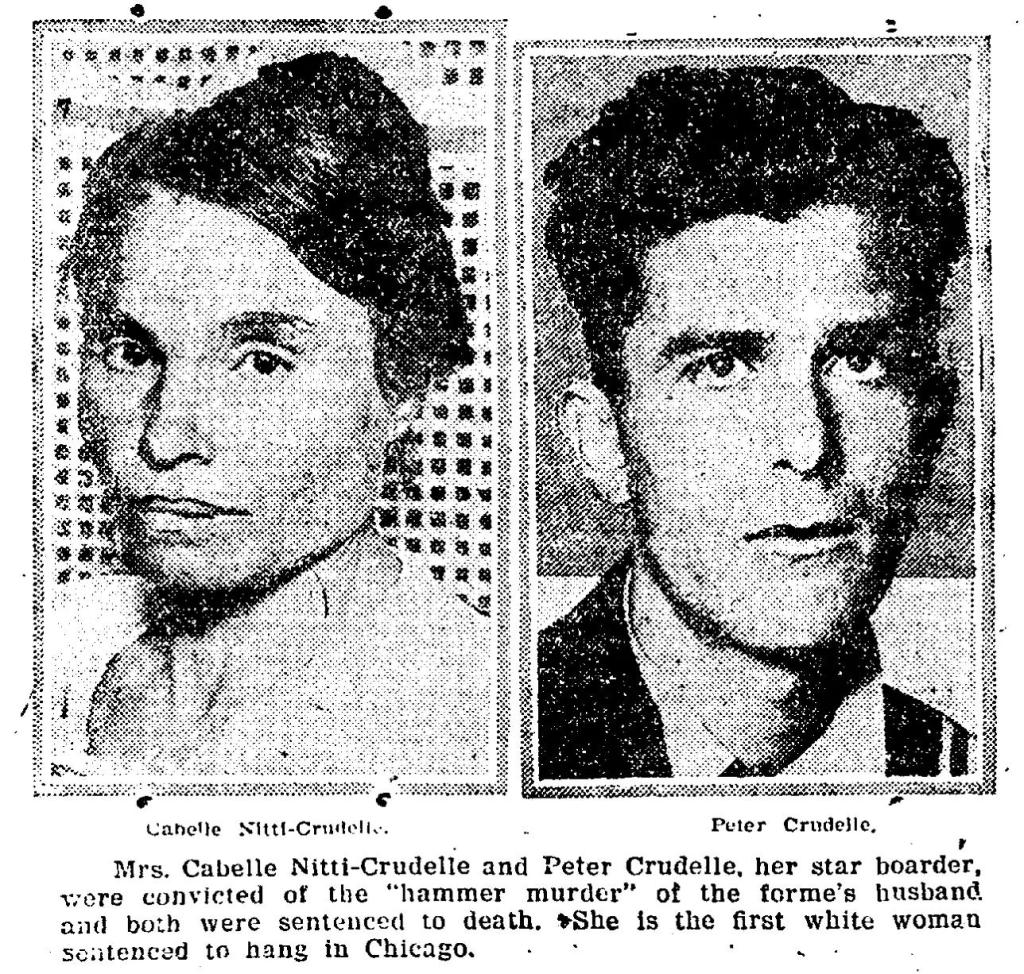

Her name was Isabella Nitti Crudelle* — and her looks alternately condemned and saved her from a trip to the scaffold.

Isabella’s ordeal began on July 29, 1922, when her husband, Frank Nitti, disappeared from their farm. Unsurprisingly, Isabella, with the aid of one of her sons, as she knew very little English at this point, reported him missing the next day. During the subsequent investigation, Isabella’s sixteen year old son Charles confessed to helping, under duress, Peter Crudelle (the Nitti’s farmhand/boarder) dispose of his father’s body in the Des Plaines River. After witnessing Isabella pinning down Frank’s hands while Peter repeatedly struck him in the head with a hammer while Frank slept under a cart. Unfortunately for the police, they had zero luck locating Frank’s corpse downriver, and without a body, the indictment against the pair was dismissed.

Endeavoring to break the case, in late September 1922, the police arrested and charged Peter and Isabella for adultery. However, whatever confession they’d hoped to extract from the couple failed to materialize and they were released. The couple would marry soon(ish) after, thus thwarting a repeat of this particular stratagem.

Fast forward to May 9, 1923: When a body was discovered in a nearby catch basin. James Nitti positively identified it as that of his brother Frank — based on a ring found on (or near, I’m not quite sure) the body. And despite Charles’s story not quite aligning (i.e., the body being found in a catch basin instead of on the banks of the Des Plaines River), the prosecutors decided to charge Peter with first-degree murder and Isabella as an accessory before and after the fact. Initially, Isabella’s son Charles was charged as an accessory after the fact, but turned state’s evidence to get out of trouble.

*I’m using Isabelle versus Sabella (the nickname used in the newspapers of the time), as it’s the name used on her headstone and two notes I’ve seen where she signed her name.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.