Ducks snoozing in a row…..(Which will become tangentially relevant in a minute.)

Soon after Alma’s death, disaster struck Louise Lindloff’s occult practice. Seems police caught wind of Louisa’s work as a clairvoyant/medium/seer and shut her down. Though she skated through the encounter without her wrists being sullied by shackles, police made it abundantly clear Louisa could no longer contact those on the otherside of the veil for coin. Unable to groom clients for possible bequests or supplement her income with readings and unwilling to curb her spending or find honest employment — Louisa turned a gimlet-eye towards her remaining child for one last big score.

While her crystal ball grew cold, Louisa toured the local insurance agencies stockpiling policies on Arthur Alfred Graunke’s life: Three totaling $515 were secured. Another, purchased on September 13, 1911, was for $1,000 and the final one for $2,000 was obtained on March 26, 1912.

With all her ducks now in a row, Louisa started the clock.

Arthur Graunke

From the Office of Full Disclosure: Most newspaper reports agree Arthur fell ill on a Wednesday — though whether it was June 5 or June 12 is a tad murky. Whichever Wednesday it was, seventy-something days after securing the last bit of insurance on Arthur’s life, Louisa served her son a meal of cucumbers, canned salmon, and ice cream. (Hopefully, not all mixed together. However, as a kid who lived through the nineteen-seventies jello mold craze? Such a hideous combo cannot be ruled out.) In any case, shortly after ingesting said meal, Arthur fell desperately ill with stomach cramps, vomiting, backaches, and other debilitating symptoms.

Once again, Louisa sent for Dr. Augustus S. Warner.

Immediately after clamping eyes on Arthur, the third member of Louisa’s family to fall desperately ill in three years, Dr. Warner finally realized he was dealing with arsenic and a serial poisoner. After treating Arthur in the best way he knew how, and with all attempts to induce Louisa into sending her son to the hospital rebuffed, Dr. Warner made a tactical retreat from 2044 Ogden Avenue.

Well aware that accusations of poisoning were grave and making an erroneous allegation could open a whole world of hurt for himself — Dr. Warner contacted a colleague to consult (unbeknownst to Louisa). After reading and discussing not only Arthur’s case but Alma and William’s, Dr. Joseph Miller came to the same conclusion as Dr. Warner: all three showed the telltale symptoms of arsenical poisoning.

Returning to Louisa’s home on June 13, 1912, strategy in hand, the two doctors tag-teamed Louisa. Blaming the wallpaper affixed to the walls of Arthur’s sickroom (a classic scapegoat), the physicians told Louisa her son’s symptoms corresponded with a textbook case of arsenic poisoning. While they “believed” Louisa didn’t have a hand in Arthur’s current complaint, they pointed out that her consistent refusal to heed their recommendation to move Arthur to a proper medical facility could be construed by some as highly suspicious in light of their diagnosis.

Reluctantly, Louisa finally acquiesced. However, replicating the scheme she used when William (her second husband) entered a similar institution, Louisa removed Dr. Warner as Arthur’s primary physician. When Arthur died, Dr. John M. Berger of University Hospital, chalked Arthur’s cause of death down as pancreatitis. Later, he admitted he’d only seen the fifteen-year-old about five minutes before said event and knew next to nothing about his colleague’s misgivings — hence the unobjectionable cause of death.

Straightaway, after learning of Arthur’s passing, Louisa sent her boarder, Henry Kuby, to Prudential Insurance Company for a blank death certificate to start the ball rolling on her last big payday.

Meanwhile, despite being barred from Arthur’s sickroom, Dr. Warner and Dr. Miller were anything but idle. Together, they compiled their paperwork and theories and took them to the Cook County Coroner and Juvenile Court Authorities. Who, in turn, didn’t waste a single second securing the proper permissions and warrants. The day after Arthur’s untimely death, whilst Louisa was planning his funeral, Captain Bernard Baer of the Fillmore Street Police Station and his officers rocked up at 2044 Ogden Avenue.

Warrants in hand, the policemen began searching the house from pillar to post while their Captain questioned Louisa. (Now, I don’t know the order in which Captain Baer fired off these queries at Louisa, so I’ll put them in an order that feels logical to me.)

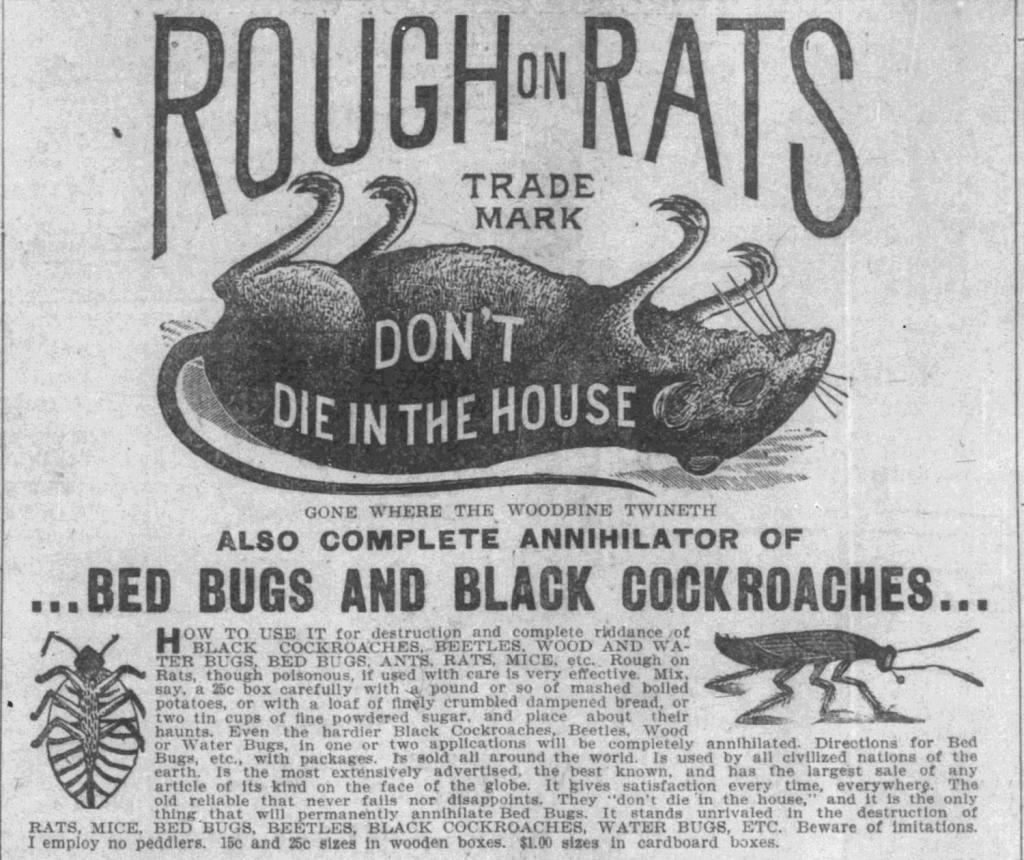

When told the reason for the search was due to Arthur being poisoned, Louisa replied: “…If he was, I know nothing of it; my hands and body are clean.” Next, when asked if she had any poison in the house, Louisa categorically denied owning any. This lie was immediately laid bare by Officer Anthony McSwiggin, who not only located a box of Rough on Rats missing about 1/3 of its contents, but some strychnine, a mercury based poison, some form of barium, and other bottles labeled poison on a pantry shelf.

Though I’ve no clue if Louisa actually owned ROR, it was such a popular and prevalent product, it would not surprise me if this was one of her sources of arsenic.

Next, investigators discovered a newly purchased grey wig (bought before Arthur’s death) and a trunk catalog. When Capt. Baer asked after these objects; Louisa admitted she planned on traveling (definitely not pulling a runner) that coming summer. An intention that did not jive with her bankbook, which showed Louisa only had $30 to her name. Furthermore, Louisa’s meticulous personal accounting showed a direct correlation betwixt the deaths of her nearest & dearest and when her bank balance dipped dangerous low.

Following these falsehoods, damning admissions, and deductions, Capt. Baer confronted Louisa with the collection of insurance policies she’d assembled on Arthur’s life. Her justification for having so many? Not only was it a German custom to heavily insure one’s immediate family members, but who would they leave such a large sum of money to, if not his mother?

Apparently, feeling this rationale wasn’t enough, Louisa explained that it seemed prudent to amass multiple policies on Arthur’s life due to the hazardous nature of his job at Commonwealth Edison Company. And faster than Jackie Robison could round the bases, Capt. Baer exposed the false underpinnings of this excuse as well. Turns out Arthur was, in fact, an office boy earning $20 a month from the electric company. What’s more, Capt. Baer discovered that Louisa deceived the insurance companies about Arthur’s age, listing it as 16 rather than 15, in order to obtain the last two high-dollar policies.

Despite all the circumstantial evidence accumulated and Capt. Baer arresting her on June 15, 1921; Louisa managed to retain her freedom until June 17, when she was formally charged with Arthur’s murder and remanded to a Cook County jail, her bid for bail denied. Though she was allowed to attend Arthur’s funeral the next day, Louisa was escorted by two city detectives and a police matron, then promptly shepherded back behind bars.

Finally, after seven years and at least eight murders, the long arm of the law caught up with Louisa. Now, the million-dollar question was: Would a Chicago jury convict her of murder?

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.