After the state recalled Dr. Miller and a Coroner’s physician to the stand, both of whom swore neither Alma nor Arthur suffered from any disease that would require treatment from an arsenic based medicine (endeavoring to rebut Sadie Ray and Louisa Lindloff’s insistence that the pair had), the state and defense made their closing arguments then rested their collective cases.

At 3:45 pm, on November 5, 1912, the jury started deliberating Louisa Lindloff’s future.

Whilst they did so, Louisa laughed and gossiped with Sadie Ray and other friends in the vacated jury box. Reporters sat in the gallery and started writing yet more copy about how a woman, even a mass murderer, couldn’t get convicted by a Cook County jury. A sentiment most spectators still sitting in the courtroom echoed, much to the despair of the Assistant States Attorneys.

Though the jury created a stir when the bailiffs escorted them to dinner at the Alexandra Hotel and again when they returned at 7:30pm — it wasn’t until a knock sounded on the jury room door at 9:15pm that the butterflies in everyone’s stomachs took flight. After shuffling back into their seats, the jury foreman rose and declared Louisa Lindloff guilty of murdering her son, Arthur Graunke, and sentenced her to twenty-five years in prison.

Seems the jury unanimously agreed on Louisa’s guilt straight away. What took the next five-ish hours to settle was Louisa’s punishment: On the jury’s first ballot – 5 wanted life in prison and 7 wanted Louisa to hang. On the second ballot – 5 voted for life in prison and 7 switched to a term of 40 years. Finally, on the third ballot – the twelve men compromised and settled on 25 years.

The resulting headlines touted Louisa as the first woman convicted by a Cook County jury in three years.

A typical article about Lulu’s crime.

A bulletin that highlights the casual racism of the day.

For you see, only one month before, in the very same judge’s courtroom, Lulu Blackwell was sentenced to thirty-five years in prison for manslaughter. The only difference? Both the Lulu and the victim, Charles Vaughn, were black. A fact which apparently made a difference to the white newspaper editors of Chicago. As not only was there significantly less coverage of Lulu’s crime and trial (in the papers I’ve got access to), when her name was mentioned either during the scant trial coverage or on the lists of women arrested for murder, most papers felt the need to point out Lulu’s skin color, and none (I found) mentioned Lulu’s stretch inside Joliet Prison being longer than Louisa’s — for a lesser charge.

Although there’s a distinct lack of copy on both the murders committed by black women and the subsequent acquittals they won during this stretch of time in Cook County, I did find a few — like Belle Beasley. Who, after five minutes of deliberation, was acquitted. Despite being found standing over her dead husband with a literal smoking gun in one hand and newspaper clippings of other women cleared of murder by Cook County juries clutched in the other.

All that being said, one of the biggest issues for Lulu’s defense was she brought a gun with her to 3212 Dearborn Street. Beyond all the typical problems associated with shooting someone in a fit of jealousy, before their house, on a public sidewalk, in front of witnesses. (Charles was planning to marry another.) By lugging the firearm to the confrontation, Lulu gave the impression, real or not, that some level of plotting went into the act. Making it that much more challenging to convince a jury that Lulu acted in either ‘the heat of the moment,’ self-defense, or needed protection under Chicago’s ‘unwritten law.’

An identical whisper of premeditation would haunt and ultimately help convict Vera Trepagnier at trial seven years later.

Then, there were the barks of laughter Lulu reportedly let loose during the testimony of the witnesses called against her. Remember, the men called to serve on Cook County juries only wanted to see overt displays of contrition, regret, and/or remorse on the faces of the women they were judging. Hence why, Billy Flynn became annoyed with Roxie (in the 2002 film adaptation of Chicago) when reporters asked during We Both Reached for the Gun if she was sorry for murdering her boyfriend and she replied, “Are you kidding?” Had Roxie continued to appear unrepentant, as she nearly did, until a state-sanctioned murder radically changed her tune — ten-to-one, she would’ve found herself facing a length of rope.

This lack of visible contrition also damned Katherine Baluk (aka Kitty Malm, aka Tiger Girl) to life in prison in 1924, for possibly shooting a security guard to death. She was also the real life inspiration for the character Go-to-Hell-Kitty in Chicago (the musical).

Though the reasons behind the jury’s decision to find Lulu guilty are only educated guesses — what isn’t — is the utter shock she displayed upon hearing the word ‘guilty’ ring out in the courtroom. An emotion Louisa would mirror thirty days later after the same exact verdict reached her ears.

While George Remus lept to his feet and motioned for a new trial — Louisa sat stock still. Only after she was led from the courtroom did she break down. After recovering from a fainting spell, Louisa wept and gave reporters this quote: “There is no justice here…Those that are guilty are turned loose and those who are innocent get the worst of it. I will show my innocence before I am through. It will only be a question of time. I did not kill my boy or any others. I am innocent, as God is my witness.”

Interestingly enough, unlike Isabella Nitti and Hilda Exlund, who blamed their conviction on their looks, Louisa didn’t. She blamed a different source: “The spirits lied to me—they lied—they told me I would be acquitted. They promised I should be free—and here I am, convicted. Why have I believed the spirits—they lie.” Though Louisa’s disillusionment in the spirit world quickly faded and new predictions of her imminent release followed — the press, her fellow spiritualists, and the public had already moved on.

Judge Windes presided over Hilda Exlund, Lulu Blackwell, & Louisa Lindloff’s trials. All of whom bucked the trend and were convicted of murder or manslaughter.

A circumstance that may have changed if Louisa’s appeal for a new trial came to fruition. And thanks to Judge Windes’ decision to allow the introduction of Julius, John Otto, Frieda, William, and Alma’s deaths into evidence — there was an excellent chance the Illinois Supreme Court would’ve approved this appeal.

Granted, the other deaths and their connected life insurance policies/payouts created a compelling pattern. However, Louisa was never formally accused of, arrested for, or tried for any death other than Arthur’s. Meaning they shouldn’t have been presented as evidence to the jury. An argument Chief Justice Carter of the Illinois Supreme Court seemed to nominally agree with, as on March 15, 1913, he issued a ‘writ of supersedeas.’ Allowing Louisa to move back to Cook County Jail’s Murderess Row while waiting for the Supreme Court to hear her appeal.

However, we will never know how the Justices would’ve ultimately ruled.

From L to R : A) The entrance to the Woman’s Prison at Joliet B) Women’s Prison Cell Block C) Two inmates making rugs D) Woman’s Dining Hall E) Female prisoners did all the laundry for themselves & the men’s prison here E) Prison Cemetery, though Louisa wasn’t buried here Lulu may have — though its unclear if the female & male inmates were buried together

On March 15, 1914, Louisa Lindloff died of intestinal cancer while waiting for her date with the Supreme Court. One of her last published quotes was, “I have nothing to say — I am happy to die.” (Sadly, Lulu Blackwell preceded Louisa beyond the pearly gates by eight months, dying of septicemia inside Joliet State Prison on July 13, 1913. The only note of her death I found was a single line in an annual report published by the Illinois prison system.)

Supreme Court appeal and protestations notwithstanding — what do I think? “There was Mrs. Green, you know, she buried five children — and every one of them insured. Well, naturally, one began to get suspicious.” Though this Miss Marple quote from The Bloodstained Pavement was written about sixteen years after Louisa Lindloff’s 1912 conviction and undoubtedly about a different poisoner, I think it neatly sums up the spirit behind Louisa’s crimes.

IMHO, it feels far too coincidental that: A) Julius Graunke & Charles Lipchow died in August, a year and three days apart from one another. B) William Lindloff & Alma Graunke also died in August, a year and a day apart from one another C) Frieda & Arthur Graunke died four years and two days apart from each other in June. John Otto Lindloff, who died in October, is the only outlier to this pattern. However, if Louisa worried he and Frieda would move beyond the easy reach of her box of Rough on Rats after they married — this might explain why she didn’t wait.

Together with the thousands of dollars, Louisa earned each time she buried someone? Plus, the lies she told the police upon discovering the insurance policies on Arthur’s life? It’s compelling, even without Sadie Ray’s uneven account of Louisa trying to slot her death into the timeline. Over and above that, Louisa’s excuse that cucumbers led to Arthur’s death is just flat ridiculous.

In other words, yes, I think she did it.

On the topic of Louisa’s Victims: After the trial concluded, Chicago Police Captain Baer went on record with his belief that on top of murdering Arthur, the rest of her immediate family, Charles Lipchow, and Eugenie Clavett — he’d uncovered evidence that Louisa had murdered fifteen more people, including a five-month-old infant. (Not to mention the countless animals witnesses swore Louisa killed while experimenting with different poisons.)

Assuming his intelligence was correct, that would bring the grand total of murders ascribed to Louisa to 23.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

Okay, so here’s the thing, before I go into the last feature of interest of Louisa Lindloff’s murder trial, we need to take a closer look at her lawyer, George Remus.

About seven after Louisa Lindloff’s trial: George relocated to Ohio and remade himself into a Prohibition-era rum-runner — after realizing how much more money he could make being a bootlegger versus defending them in court. Using his skills as a former pharmacist whilst applying his law degree, Remus found/utilized a loophole in the Volstead Act to make millions from both legitimate and illicit whiskey sales.

Predictably, the King of Bootleggers’ business plan rapidly pinged the police’s radar.

On May 17, 1922: George was found guilty of violating the aforementioned Act and sentenced to two years in Atlanta’s federal prison.

Now, according to George Remus, this is what went down next: While serving his sentence, Franklin L. Dodge Jr., an undercover prohibition agent, managed to prise from George the information that he’d given his second wife, Imogene Holmes, power of attorney over his dream home, vast fortune, and bootlegging operation. (George’s first wife divorced him after discovering he was carrying on with Imogene on the side.) However, rather than reporting this juice tidbit to his superiors, Franklin supposedly resigned his post and promptly seduced Imogene.

At this point, the pair proceeded to liquidate George’s personal and professional assets. Secreting away the resulting money from both the government and George.

Understandably fearful of retribution, Imogene and Franklin began plotting. First, Franklin attempted to persuade his former colleagues to deport George back to Germany, where he originally hailed from. When that scheme crashed and burned, the two turned to violence and hired a hitman. However, said assassin, apparently afraid of being double-crossed, kept the $15,000 fee and briefed Remus about the plan instead.

Fully aware of George’s mounting fury and at wit’s end, Imogene and Franklin went into hiding. Unfortunately, this strategy conflicted with the divorce proceedings Imogene initially filed for on August 25, 1925 (two days before George was released from Federal Prison). Due to several lengthy delays, the dissolution date was finally set for October 6, 1927.

A few hours before she was due in court, Imogene and her teenage daughter (not fathered by George) left their Cincinnati Hotel and hailed a cab. On her way to her lawyer’s office, Imogene spotted George and his chauffeur following them.

When traffic unexpectedly slowed to a crawl around Eden Park and/or George’s chauffeur forced the cab into the parking lane (it’s unclear from what I read which way it happened), Imogene panicked. Leaving her daughter in the relative safety of the cab, Imogene hopped out and fled into the public park. Unwilling to let his quarry flee, George flew from his ride whilst shouting four-letter epithets at Imogene’s retreating form.

In short order, George caught up with his estranged wife and, before anyone could intervene, George shot Imogene in the abdomen. A wound she would die from the same day, despite being rushed to hospital by good Samaritans and surgeons doing their level best to save her.

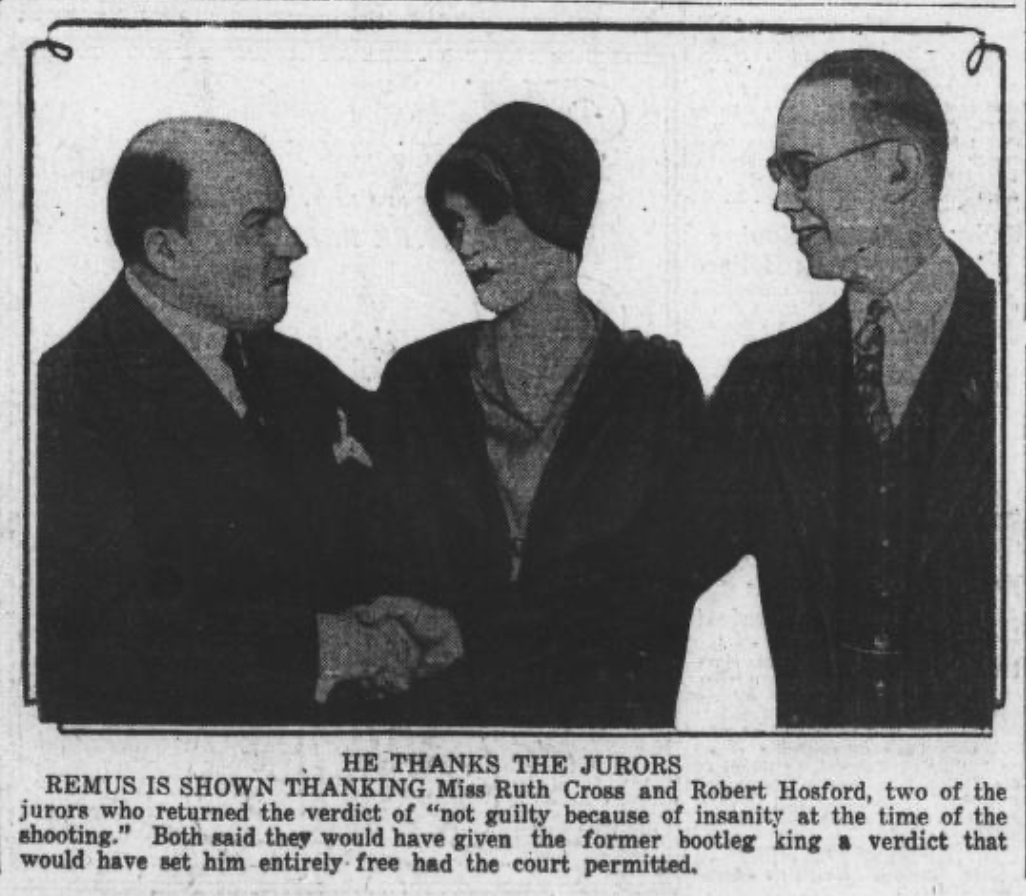

Obviously, George went on trial for Imogene’s murder.

Using ‘temporary insanity’, a defense George helped pioneer, he and his lawyer managed to secure a not-guilty by reason of insanity verdict. Though Ohio authorities committed him to a state-sanctioned asylum afterwards, George would only stay within its walls for a few months before being released. And, due to the ASA’s arguments during his trial, the courts would not allow the state to retry George for Imogene’s murder — leaving him free as a proverbial bird. (George would later go into real estate, marry his secretary, and die in 1952.)

Now, what does George’s sins have to do with the price of maple syrup in Canada?

Well, in my estimation, it shows a degree of ethical elasticity. An understatement in light of Imogene’s murder, I know, but up until that point, it seems George was content following the same crooked path as Aristide Leonides.

Aristide Leonides being the pivotal character in Agatha Christie’s Crooked House. Who, amongst other things, habitually twisted the law to suit his needs. Thus allowing him to skate just this side of trouble as he never technically broke the law. A tactic George successfully employed whilst setting up and administering his rum-running racket.

That being said, an unscrupulous streak that eventually grows wide enough to condone murder needs to start somewhere — generally, with minor misdeeds. Which you can find in George’s history. While still in Chicago, in April of 1913, George was officially charged of trying to bribe a witness during a divorce case, and in 1917, he was accused of conspiring to extort $15,000 from a prominent banker for breach of promise.

Though neither episode, as far as I can tell, resulted in any disciplinary action — the Illinois Supreme Court did disbar George on October 6, 1922 after his bootlegging conviction.

This moral malleability, I believe, reared its ugly head during Louisa Lindloff’s trial in October/November of 1912. For you see, until the morning of October 26, Assistant States Attorneys Lowe & Smith considered Ms. Sadie Ray their star witness. As Louisa’s housekeeper from approximately November of 1911 until Louisa’s arrest in June of 1912 — Sadie was on hand during Alma and Arthur’s last days.

Though she didn’t testify before the Grand Jury, since the ASAs wanted some of their evidence to stay secret until trial, ASA Smith & Lowe did interview Sadie extensively behind closed doors. Where she told them, during her time at 2044 Ogden Avenue, that Louisa had not only predicted the date she would die — but advised Sadie to take out a life insurance policy naming Louisa as the beneficiary. After this conversation, which occurred only weeks before Arthur’s death, Sadie became seriously ill after eating a meal prepared by Louisa. Moreover, Sadie told the ASAs about the glasses of water Louisa gave Arthur, who in turn routinely complained about them being “sandy” and burning his throat. (FYI: Arsenic does not dissolve well in cold water, hence why the “sandiness” was so important.)

On October 26, 1912: However, when Sadie climbed into the witness chair, her testimony for the prosecution was lackluster at best.

Though she confirmed becoming sick after a meal at Louisa’s house and the insurance policy request, Sadie now recalled that Louisa only put the finishing touches on the dishes and that she’d actually prepared the bulk of the food. Sadie dulled her testimony about Arthur’s “sandy water” by tacking on that he was always “kicking off” about one thing or another during his final illness. When asked if she’d seen Louisa adding strange substances to Arthur’s food or refused to administer the medicine prescribed by his doctor, information the ASA’s seemed to expect affirmations of — Sadie replied, “I don’t remember.”

Let down by her information and suspecting undue influence, someone (apparently) put Sadie under surveillance.

October 29, 1912: This scrutiny that quickly bore fruit. When not only did one of Captain Baer’s men observe George Remus driving Sadie to court in his car, but (on another occasion) witnessed Sadie attempting to induce another state’s witness into accompanying her inside George Remus’s office building. When she refused, Sadie dashed into the building, returning minutes later with Remus in tow. Whereupon the legal professional began pressuring the witness to agree to testify that Louisa “had always been good to her family.”

When Capt. Baer confronted Sadie in a courthouse hallway with this intelligence and threatened to arrest her — she was defiant. “I’m a poor girl…Why shouldn’t I take an automobile ride when I have the chance?…I haven’t tried to influence anybody. And nobody has tried to influence me.” As for George, he claimed Sadie was a family friend, and the ride to the courthouse was just a simple “courtesy.”

The next day, George attempted to have Capt. Baer cited for contempt of court for trying to “intimidate” a witness. Although this gambit didn’t work, it did result in all the other state witnesses being put under police protection (as Sadie had been seen approaching others).

October 31, 1912: In a move that startled everyone present, George Remus recalled Sadie to the stand. During this second session of questioning — Sadie gave testimony that blatantly contradicted several remarks she’d made on the state’s behalf while calling Louisa a caring mother and corroborating Louisa’s assertion that both Alma & Arthur took patent medicine for a skin complaint that ran in the family.

Granted, it’s within the realm of possibility that Sadie’s memory grew a tad fuzzy in the three months before Louisa’s trial, and what Capt. Baer’s men witnessed was completely innocent — however, I don’t buy it. I think George either paid Sadie in cash or favor to tank her testimony for the prosecution and/or played on Sadie’s loyalty to Louisa to do the same.

Moreover, I don’t think this was the only testimonial U-turn George managed to buy.

November 2, 1912: When Mrs. Alvina Rabe (John Otto and William Lindloff’s mother) testified before a packed Chicago courtroom — she told the jury how kind Louisa was to John Otto, a good wife to William, and her belief that both her sons had died from natural causes. A stark contrast to her words during the Coroner’s Inquest in Milwaukee, when she called Louisa a murderer.

While no one, as far as I can tell, was ever charged with perjury, contempt, or witness tampering after Louisa’s trial. I find it difficult to believe that not one but two star witnesses for the prosecution serendipitously switched sides at the eleventh hour. Especially since we know from ensuing events that George wasn’t above bending/breaking the law when it suited his purposes. Whether by using a portion of the $59,000 (in today’s money) that Louisa’s supporters raised on her behalf or his silver tongue — I don’t know.

However, as Agatha Christie (might’ve) said: “One coincidence is just a coincidence, two coincidences are a clue, three coincidences are proof.” Though I don’t see a third (that doesn’t mean it isn’t there), I believe George Remus attempted to stack the deck in Louisa’s favor upon realizing how deep the waters against her were.

Not that it mattered.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

Possible tools of Louisa’s trade.

Now that Louisa Lindloff’s lawyer, George Remus, dealt with the arsenic hued elephant in the (court)room, it was time to address a far more problematic aspect of the case — Louisa’s pinpoint prophesies of death. Obviously, correctly predicting the exact expiration date for (at least) seven separate people is a tough mountain for any defense to climb. Yet, this peak wasn’t insurmountable, thanks to the mercurial nature of Chicago juries and the well-established Murderess Acquittal Formula.

However, the climb did prove far more treacherous than first anticipated after Judge Thomas G. Windes allowed Assistant State’s Attorneys Smith & Lowe to introduce the deaths of Julius Graunke, John Otto Lindloff, William Lindloff, Frieda Graunke, and Alma Graunke as well as, the corresponding life insurance payouts into evidence. These deaths, when taken in conjunction with Arthur’s (the only family member Louisa was actually on trial for murdering) and the ledger found secreted away beneath a floorboard in Louisa’s wardrobe (which demonstrated the correlation between Louisa’s dipping bank balance and the alleged murders) made the pattern crystal clear.

Though this judicial decision was problematic, it didn’t seem to alter the razzle-dazzle strategy Louisa and her legal team set in motion in the run-up to her trial in November 1912.

Now, you need to understand that by the time Louisa’s alleged crimes came to light, Spiritualism was simultaneously flourishing and floundering in the United States. Spurred on by grieving families who lost fathers, husbands, brothers, and other relatives in brutal battles during the Civil War (forty-seven years before), this idea that the spirit remained intact after death and could be contacted brought genuine solace to those in mourning. (Spiritualism saw a similar uptick in popularity after WWI as well. Hence its inclusion in so many golden age mystery stories, including a Miss Marple short story, Motive v. Opportunity.)

Unfortunately, it didn’t take long for those with an eye for the main chance to start taking advantage. Now, to be fair, some spiritualists sincerely wanted to help the bereaved and those searching for answers. However, a far greater number chose to twist Spiritualism for their own gain.

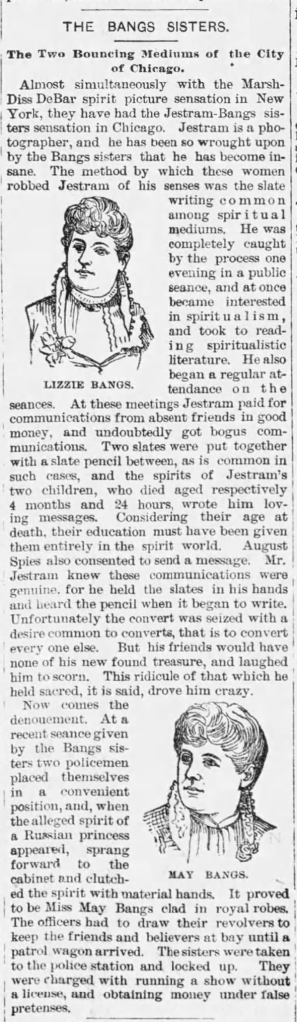

Like Chicago’s own Bangs Sisters.

Operating out of their parlor, May and Lizzie conducted seances during which the spirits sometimes “created” either writings or portraits for their still-living loved ones — for a hefty fee.

The first article about how the Bangs Sisters drove a prominent Chicago photographer, Henry Jestram, insane with messages from the dead. Many in Chicago blamed the pair for Jestram’s commitment and subsequent death inside an insane asylum. The second photo is (obviously) of Mary “May” Bangs and her ex-husband – who married her because his dead mother “told” him to do so.

However, by the time Louisa’s trial came around in 1912, a massive number of mediums, fortunetellers, and their ilk had been publicly unmasked as frauds. (Including the Bangs Sisters, who had their deceit exposed once in 1901, again in 1909, and finally sometime before 1913.)

Yet, despite the growing body of evidence compiled by scientists, magicians, and authorities demonstrating the literal tricks of the trade — people still wanted to believe.

Just some of the coverage Spiritualism received back in the day. From L to R: A) When one did not own a crystal ball, a glass of water would work equally well for seeing into the future. B) Spirit boards were often employed by mediums. C) An “authentic” spirit drawing. D) Sir Arthur Conan Doyle being photo bombed by fairies, now debunked. E) An advertisement/bio of a clairvoyant. E) A “ghost” appearing during a seance.

Whether Louisa counted herself as a true believer or amongst the double dealers hardly matters.

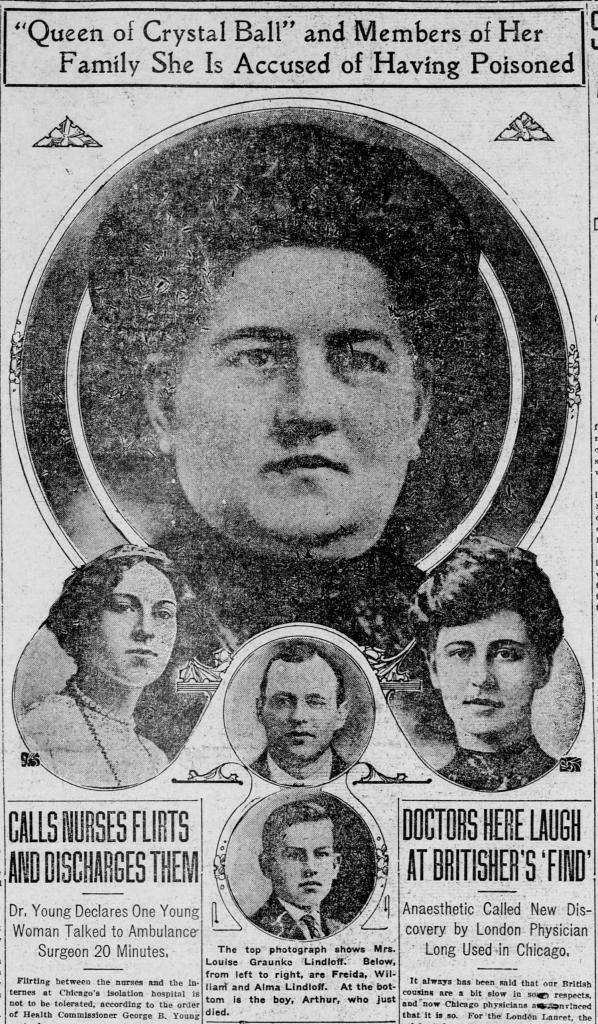

What does signify is the fact that within short order upon arriving at Cook County’s Murderess Row, Louisa leaned heavily into her advertised occupation of spiritualist medium. To this end, Louisa installed her favorite crystal ball within her jail cell. When reporters asked about the clear sphere, Louisa proudly boasted she’d paid $500 for the instrument, which contained a single tear shed by Cleopatra over Marc Anthony’s resting place within its heart. When used with her own second sight, this extraordinarily powerful reagent would swell and stretch beneath her gaze until images from the future filled her vision and/or she contacted someone across the River Styx.

Unsurprisingly, Louisa used the crystalline orb to contact the son she was accused of murdering: “She says that she has communicated thus with Arthur, and that he tells her she will be exonerated, but that she is unable to get in touch with her late husband Wm. Lindloff. However, she is assured that Arthur will look him up.” This prediction, made just eleven days after Arthur’s death, was one of the first in a lengthy string of prophesies Louisa would deliver to anyone and everyone in earshot.

And many were listening.

Amongst Louisa’s most vocal supporters were her fellow mediums, necromancers, and the like. During Louisa’s many and varied court appearances, these spiritualists routinely relayed their visions and spirit guide messages to reporters — all of which confirmed Louisa’s gifts, innocence, and imminent acquittal. Moreover, they and sympathetic members of the public contributed to Louisa’s defense fund, raising well over $1,800.

The close ups of her mouth and nose were trying to show the paper’s readers how Louisa’s features identified her as a murderer.

Although the state’s tests and investigation of Louisa’s crystal ball revealed it to be nothing more than a fifty-cent orb of glass, this information did not (seemingly) affect Louisa’s clients’ faith. Although ASA Smith & Lowe compelled a few to corroborate that Louisa had predicted the exact dates of several familial deaths (which Louisa later denied doing). They also testified to numerous predictions Louisa made that came about, which she couldn’t possibly have influenced the outcome of. (Louisa also made similar death day prophecies to Dr. Warner for Alma and Arthur’s death and predicted Arthur’s death at Alma’s funeral to her favorite Undertaker.)

(BTW: The loss of access to said sphere for police testing did not stem the tide of Louisa’s predictions. Instead, she would perform long, complicated divination rituals before an altar constructed from a framed photograph of Arthur and gifts he’d given her to achieve the same results.)

To the jaded eye, this spiritualist angle appears to be nothing but a bunch of balderdash meant to feed the press and distract the public from the correlation between death and benefits. If it also happened to plant the idea Louisa was far too silly to commit such ruthless acts, so much the better.

Another headline of Louisa’s alleged crimes.

Next, George Remus attempted to fashion Louisa into a sympathetic figure caught in a web of circumstances far beyond her control.

To this end, and to the complete surprise of everyone, Louisa included a hitherto unmentioned death while testifying in her own defense. Fourteen years before Julius’s death in 1905, Louisa and Julius’s infant son, Erick Graunke, died unexpectedly in 1891. In the article I read, there wasn’t a clear reason why Louisa brought Erick and his death up….Other than trying to garner sympathy from the jury? And/or hoping to get remains tested for arsenic, knowing none would be found, thereby breaking the pattern? I know it sounds unkind to intimate Louisa used her baby’s death for her own ends, but up until this point, he’d not come up once. So why now? It just seems…..well…..slightly shady that she would bring up his death at this point in time when no one in either Wisconsin or Illinois had once questioned it.

(And this wasn’t the only time Louisa might’ve used an infant for her own ends. According to Captain Baer and Milwaukee prosecutors, there was a fair chance Louisa experimented with arsenic or other substances on a five-month-old infant she helped care for, leading to their death in 1907.)

Next, during her nearly two hours on the stand, Louisa elaborated on several tidbits she had shared with the press earlier in her incarceration. First, she painted her first husband, Julius Graunke, as a serial adulterer. Who passed a STD to her, and she unsuspectingly gave her children and second husband. Moreover, after mustering the courage to leave him, Julius tricked her into a reconciliation three months later. (BTW: While her neighbors in Milwaukee neither confirmed nor denied Louisa’s account in the articles I read, MANY testified to the fact they suspected she was carrying on with another man before, during, and after Julius’s last illness.)

Following her harsh account of Julius, Louisa portrayed John Otto Lindloff as a drunk whom neither she nor his brother/her future husband wanted marrying Frieda (Louisa’s eldest daughter).

At this point, Louisa donned the mantle of a long-suffering mother whose other daughter (Alma) routinely stayed out all night drinking and dancing. Utterly undeterred by Louisa’s warnings about her frail health or “whippings” she received, Alma continued to do as she pleased until her fast lifestyle caught up with her. (Whether these “whippings” were physical or verbal is unclear). Finally, Louisa painted herself and Arthur as victims. He, being a “good boy”, was forced to endure an STD he’d done nothing to earn. While she helplessly watched everyone she loved fall like dominoes due to the unexpected consequences of the arsenic laced medicines they all were compelled to take due to Julius’s infidelity.

Now, with the arsenic accounted for, circumstances sufficiently muddied, and a sympathetic tale on record, George Remus turned his sights on the last problem sticking in the proverbial craw of his defense — a one Miss Sadie Ray.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

Okay, not all photos can be winners….

Tomatoes are so much fun to cook with….

You must be logged in to post a comment.