About the time Constance and Gwenyth fade from sight, their youngest sibling comes into view.

While included in a couple of U.S. censuses and passenger records in various ports of call, the youngest of the Little’s brood, Iris, doesn’t really come into focus until becoming the 1934 Women’s Table Tennis Champion. At this tournament, or perhaps the one the year before, Iris met her future husband Sydney Heitner (who’d won the men’s single division in 1933 and the mixed doubles in 1935). The two would marry sometime around 1935 (and definitely before 1938, as her father’s obituary uses her married name).

Fast forward to 1950.

Iris and Sydney are living at 32 Stephen Oval in Glen Cove, NY, with their two daughters — Jessie (age 9) and Sheryl (age 7), with a third baby (a boy later named Robert) on the way. Now 39 and an insurance broker, Sydney still participated in table tennis tournaments. One such contest drew him to New York City on March 30, 1950.

He never came home.

Detective John Quinn (of the Nassau County Missing Persons Squad), who’d been assigned the case, pinned down Sydney’s last confirmed sighting to a bar on 15th Street and Fifth in NYC. At first, Detective Quinn thought foul play of one kind or another occurred; however, as days passed, he found no evidence one way to the other. With all the available clues rapidly run to ground and the case growing colder by the day, the detective turned to the public for help.

On May 19, nearly three weeks after Sydney vanished into thin air, newspapers started running pieces citing the bare bones of the case and Sydney’s vital statistics.

Iris, undoubtedly warned of the impending publicity, “prostrate” at the disappearance of her husband, and pregnant — took herself and her daughters to Maplewood (New Jersey) to stay with one of her brothers. A move which not only spared Iris from answering the standard battery of intrusive questions from reporters — it also protected her from addressing the gossip her next-door neighbors were more than willing to dish about the couple.

Seems they told reporters Sydney and Iris recently “had a falling out”. Though the papers didn’t report what the pair argued over, Max Heitner (Sydney’s brother) refuted their claims by going on the record: “They have been married for 15 years and always appeared very happy.”

Speaking of Max, with Iris out of reach in New Jersey, her brother-in-law stepped into the informational breach. Supplying one reporter with Sydney’s photo and quote defending his sister-in-law in one breath…..…..And in the next, he provided the possible reason for such a marital clash to a different reporter.

According to the Brooklynn resident, he was the last friend or family member to see Sydney in the flesh. Admitting Sydney asked him to drop himself and a “beautiful tall” lady-friend off at the 69th Regiment Armory to watch a roller derby bout. Though he couldn’t recall her name, Max did say this unknown woman disclosed a love of rollerskating and the ownership of a black four-door Oldsmobile.

(BTW: From what I can suss out, the building hosting the roller derby is within walking distance from the bar where Detective Quinn said Sydney was last seen. So Max’s story could be true.)

Odder still, this wasn’t Max’s only conflicting account.

After declaring his brother without a single enemy in the world….Max admitted he could not entirely brush aside the notion Sydney was kidnapped. Nor could Max discount the idea of murder, theorizing some hitherto unknown professional rival could’ve done away with his brother over a deal Sydney was due to broker (the day after he melted into the ether) that would’ve netted him a million-and-a-half-dollar commission.

The only explanation Max summarily dismissed was the suggestion Sydney was off somewhere suffering from amnesia, saying, “…it had never occurred in his family.”

From the Office of Fairness: It’s more than likely Max was beside himself with worry over his brother’s unknown fate. I know I would be if a sibling of mine vanished with only the clothes on their back and the change in their pockets. Moreover, I could totally see myself struck with a case of verbal diarrhea, which inevitably would lead me to spout off every theory and bit of info, no matter how trivial, to reporters, hoping it would lead to a breakthrough in the case…..Even the stuff which might place an unflattering light upon them.

However, the Miss Marple living within my brain wonders if the variety pack of mismatched details Max flung like confetti at reporters was really meant to muddy the waters while his brother fled to a new life, possibly in Austria, where Max and Sydney’s family originally hailed from — or — according to a rumor printed in Table Tennis Magazine 45 years later, to Florida “…to risk being a freedom-minded cab driver. Later he died under strange circumstances. Or someone had heard.” (BTW: I have not been able to verify a word of this rumor.)

In any case, while not probable, it is just possible Max Heitner possessed the correct connections to hook Sydney up with forged documents, which allowed him to vanish without a trace……Seems, in the summer of 1940, Max Heitner and his wife met one Benjamin Tannenbaum while on vacation. Apparently, Benjamin and Max hit it off so well that by the time winter of 1941 rolled around, Tannenbaum was renting a room in Max’s apartment when he wasn’t on the road for work. Even better, Tannenbaum was an accountant and helped Max with the books for the apartment building he managed (and lived in) for his brother-in-law.

Everything was hunky-dory until 9:30pm on February 6, 1941.

That’s when Bertha Lipzitz heard a commotion coming from the Heitner’s apartment….followed by five gunshots. Waiting until she heard footsteps receding down the hallway, Bertha scurried down to the building’s super, who in turn called the police.

Entering Heitner’s home through an open window on the fire escape, police discovered signs of a struggle, a discarded blackjack, and Benjamin Tannenbaum’s dead body (with two bullet holes) in the apartment’s hallway and four-month-old Paulette Heitner, who Tannenbaum had been babysitting, asleep in her crib.

Police detectives thought the baby, who remained sound asleep under the watchful eye of a detective for the majority of their crime scene search, was the biggest surprise the night would hold….until the fingerprints of the dead man came back.

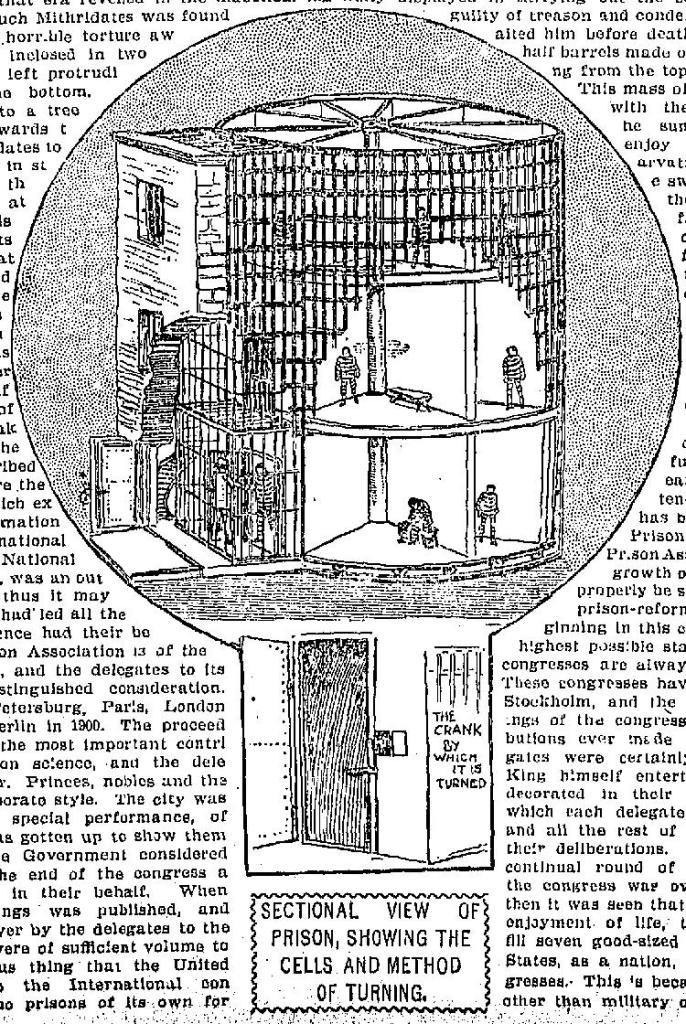

Pics of Louis “Lepke” Buchalter and Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro

It turns out the nice, polite, and respectable accountant was none other than Benjamin “Benny The Boss” Tannenbaum — the notorious strong-arm man and accountant for Louis “Lepke” Buchalter and Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro. A duo responsible for all kinds of crimes — including prostitution, racketeering, and the creation of Murder, Inc. (An enterprise that insulated organized crime families from the murders they wanted done by providing a fleet of unconnected contract killers, and zero paper trail.)

On the other side of the law at this point in time was Thomas E. Dewy. A special prosecutor for New York County whose sole job was to pursue, prosecute, and convict every member of the organized crime families operating in New York.

Apparently, Dewey was very good at his job.

Of course, this led to no small amount of paranoia amongst the upper echelons of these crime syndicates. Anyone whom the bosses even suspected might’ve spoken to Dewey (or a member of his crew) or was targetted by the lawyer for grooming as an informant was summarily executed.

Hence the fatal visit to Heitner’s apartment. (It’s unclear if any of the aforementioned particulars applied to Tannenbaum, but apparently, no one wanted to take the chance.)

By the time Max Heitner and his wife returned home to 40 Featherbed Lane in the Bronx, shortly before 2am (she from a visit with a friend and Max from the movies), their apartment, the building, and the surrounding neighborhood were crawling with police.

Unfortunately for Max, he’d been convicted on September 10, 1936, for “possession of policy slips” (basically, he was caught gambling and was given a $50 fine for it). This conviction allowed the police to arrest Max after they found two loaded revolvers in his apartment. An arrest that feels more than a little like a pretext so Dewey’s task force could tighten the screws on Max over his relationship with Tannenbaum, whom they thought “…had never been known to engage in any legitimate business unconnected with racketeering.”

And whilst I believe Max’s courtroom denial of being clueless about the loaded firearms in his home. I am highly skeptical of Max’s claim he’d no inkling of Tannenbaum’s employment or employers. (BTW: I don’t know if Max Heitner was convicted on the weapon’s charge or not. After reporting he made it out of police custody on February 9th or 10th on $2,500 bail, there’s nothing. At least that I could find.)

Hence, I think it’s possible but not probable Max had the connections to secure the fake papers Sydney would need to vanish without a trace nine years later.

Or maybe Sydney just walked out on his life — without anyone’s assistance. He wouldn’t be the first husband to abandon his family for a fresh start. Or maybe this unidentified “beautiful tall” woman overheard Sydney speaking to Max about the massive lumpsum he was coming into, missed the part where he said the deal was on the morrow, and lured Sydney away from the bar on 15th and 5th to a location where some less-than-savory confederates jumped him and, in the scuffle, accidentally killed him.

Ultimately, Sydney Heitner’s fate remains unknown.

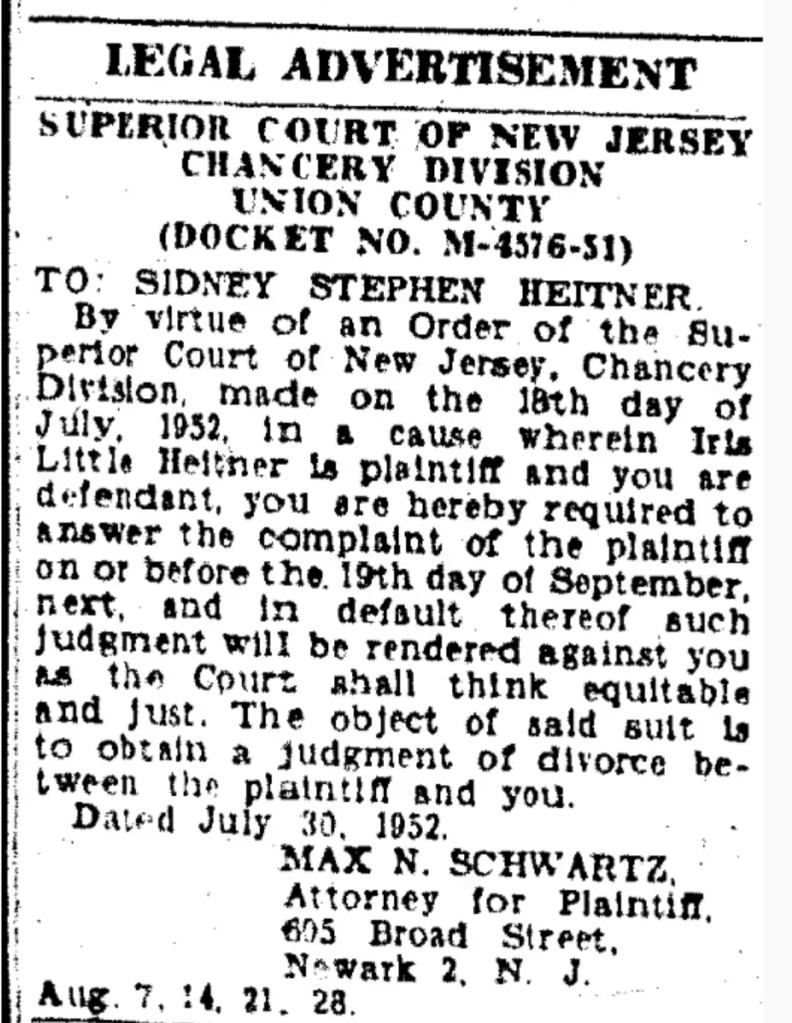

At least to the public at large. Interestingly, on July 30, 1952 — Iris Heitner started divorce proceedings against Sydney, which suggests she believed Sydney was still alive somewhere since she didn’t simply wait a bit longer and have him declared legally dead. (Though that could’ve been due to family politics.)

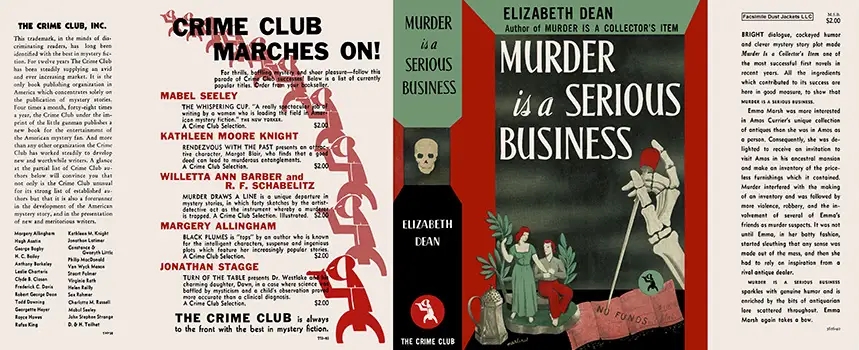

And it’s within this unsettling interim period (1951 & 1952), Iris published her only two mysteries, Board Stiff and Death Wears Pink Shoes.

And just like that — Iris Little Heitner, Constance & Gwenyth Little, and all their mysteries faded from the public eye.

My 52 weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.