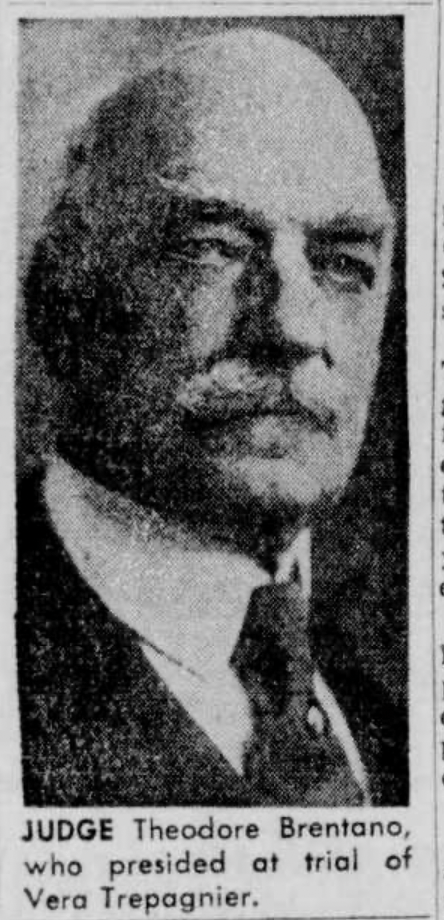

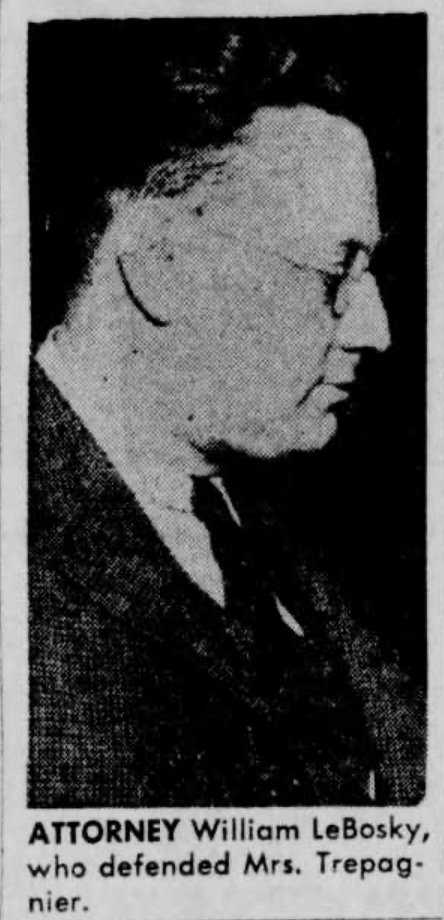

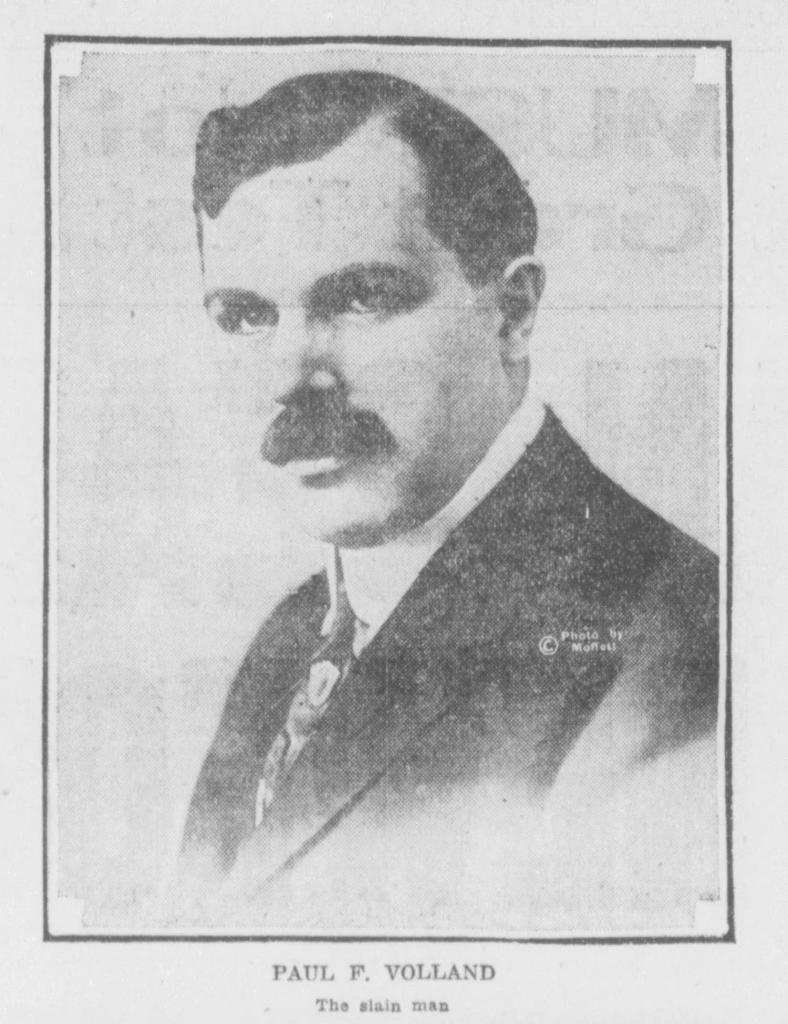

On July 15, 1919, at 5:50 pm, after three ballots — the jury found Vera Trepagnier guilty of manslaughter and fixed a sentence of one year to life in prison. Paul F. Volland’s second ex-wife, Gladys Couch Volland, and his son, Gordon B. Volland, were both in court when the verdict was announced and applauded (metaphorically) the jury for holding Vera accountable for her actions. Unsurprisingly, State’s Attorney Hoyne lauded the victory of ASA Dwight and the jury’s decision.

So what went wrong? Why did the jury find Vera guilty of manslaughter despite her lawyers following the formula that got 26 other women acquitted?

Vera blamed the loss on another attorney, Frances E. Spooner — the only lawyer she’d found who agreed to fight the unbalanced contract she’d signed with Paul F. Volland in civil court. In an interview given shortly after her conviction, Vera claimed Spooner hamstrung her defense because she “…had all my papers about the case that led up to the killing, and she left town.” Which could be true? The one and only time I found Spooner’s name linked with Vera’s occurred the day after Vera’s bid for a new trial was denied, on August 16, 1919: When the papers reported Spooner was suing her former client for breach of contract, “…by killing Volland, she brought an end to the case and threw the plaintiff out of a job.” (I’ve no clue how this case ultimately panned out.)

However, it’s equally possible Vera’s all-male defense team used Spooner as a convenient scapegoat to cover the collective backsides with their client after their loss. Spooner, one of the rare female attorneys in Chicago during this period, would make an easy target in any post-trial blame game.

Weighing in, over 100 years later, I see the scales of recrimination tipping ever so slightly in the direction of Vera’s cadre of lawyers and their decision to rely solely on Vera’s testimony.

Why? First and foremost, Vera’s account doesn’t quite add up, in my estimation.

While it’s possible Vera’s version of events unfolded exactly as she said……Why would Volland start strangling her for simply refusing to leave his office? Granted, Vera had become a thorn in Volland’s paw. However, until that afternoon, he’d successfully kept her at arm’s length for years through a lack of communication, lawyers, and by using layers of security/secretaries/doormen as a shield. Moreover, if Vera failed to leave Volland’s office because he murdered her (worst case scenario) or she exited under her own power with hand-shaped bruises around her neck, disheveled from a struggle, and gasping — it would’ve been noticed by the office full of people working away in the middle of the day.

Speaking of people, while there weren’t any eyewitnesses other than Vera who saw what happened in Volland’s office, two individuals were close enough to hear some of what was happening inside. Both women spoke of hearing Vera’s voice growing louder and shriller as the interview went on while Volland’s remained low and even. Suggesting it was she, not him, who grew furious as the conversation continued.

Mrs. Gladys Crouch Volland

The defense, in an attempt to shore up Vera’s assertion Volland struck first, claimed Volland was a “wife beater” and “woman-hater” which led to the dissolution of his second marriage. The only problem? Said second wife, Gladys Crouch Volland, still resided in Chicago and was more than willing to testify that her ex-husband never abused her or their daughters, nor was cruelty the reason why she sued for divorce. While it’s possible Gladys was lying, the fact she wasn’t called to the stand or her divorce decree read aloud by the defense — who’d subpoenaed her — suggests they couldn’t scrounge up enough proof that Volland abused his ex-wife to convince the presiding Judge to allow it into evidence. Making it likely that Vera’s attorneys simply spliced the idea into their opening remarks in the hopes that the jury would consider the unsubstantiated claim during their deliberations.

Furthermore, I found an announcement for Volland’s 1904 divorce from Laura Gordon Volland, his first ex-wife. While one of the gossipy articles alluded to money at the root of the marriage’s dissolution, none mentioned cruelty. (And the fact Laura remarried mere days after the finalization of the divorce decree hints at a different set of problems within the union.)

In my humble opinion? Upon realizing Volland wasn’t going to willingly hand back her miniature or write a check for five grand, Vera pulled a revolver on him and that’s when Volland “lept at her” — not the other way around.

This fine — yet important distinction — is why Billy Flynn, in the musical Chicago, worked so hard to make sure the newspapers reported that Roxie Hart and her lover both reached for the gun. If it came out that Roxie pulled the gun on her boyfriend first, in a fit of rage rather than in self-defense, it would’ve negated her claim to the “unwritten law.”

After her arrest, in an effort to invoke said statute for herself, Vera neatly summed up the “unwritten law” as this: “In my State men may lie, gamble, cheat in business, but they do not lay hands on a woman.” As I understand it, this tacit law allowed judges and juries to protect abused women who either snapped or needed to defend themselves at a point in time when domestic violence laws were nearly nonexistent. More importantly, it’s part of the foundation on which the murderess acquittal formula rested — hence why, in my opinion, it’s more than likely Vera swapped up the order of events to save her own skin.

Unfortunately for Vera, her uneven account wasn’t the only problem.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.