Amongst the treasure trove of Golden Age mysteries, we find Sherlock Holmes enjoying his seven percent solution, Philip Marlowe’s prodigious drinking makes the characters in Mad Men look like teetotalers, Elizabeth Daly pitted Henry Gamadge against a heroin addict in Somewhere In The House, and Dorothy L. Sayers engineered a plot where Lord Peter Wimsey broke up a cocaine ring in Murder Must Advertise…These and a title wave of like-minded plots prove Golden Age mystery writers (and those from the surrounding decades) didn’t shy away from including alcohol and/or illicit substances in their works.

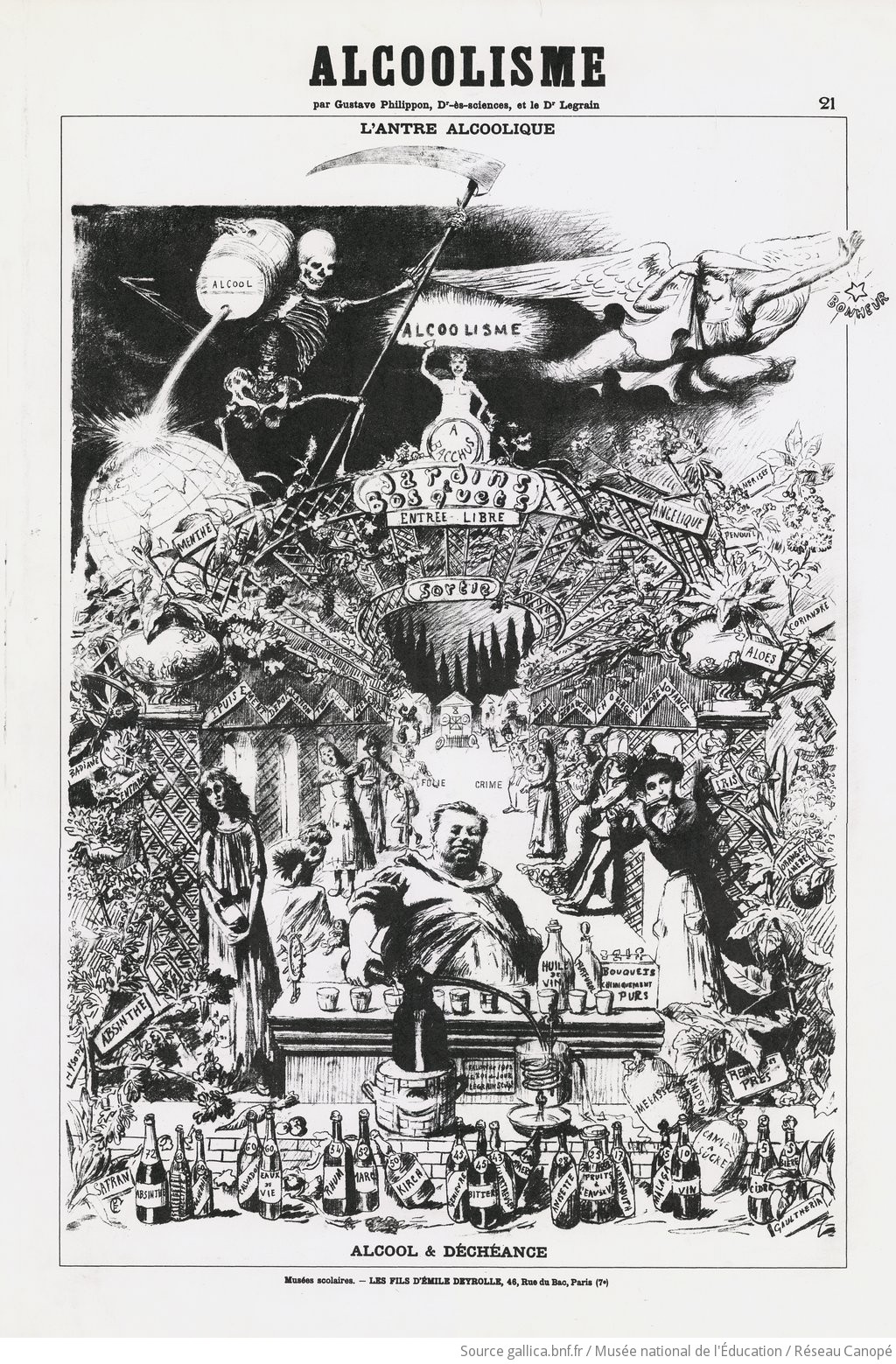

Yet absinthe, the purported creator of fiends and madmen, rarely gets mentioned.

Above and beyond the fact that the “Absinthe Defense” repeatedly fell short in courtrooms, thereby making it less appealing as a McGuffin for writers, I think there are a couple of other factors as to why “Absinthe made me do it!” never became a trope in mysteries. (Or at least not among the tomes I’ve helped collectors locate or in the reprints I’ve cracked the covers of.)

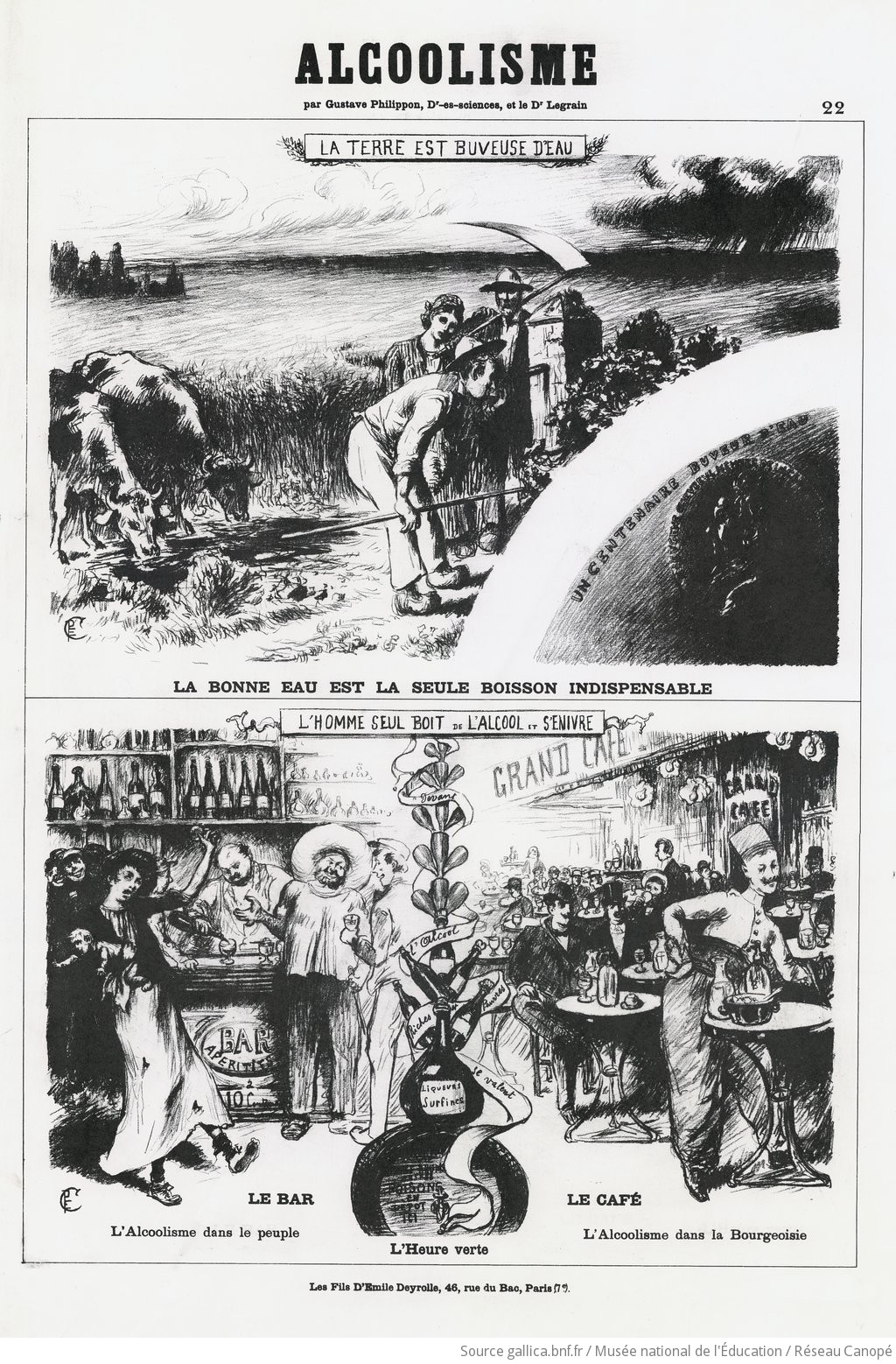

First and foremost, UK scientists and physicians gave Magnan’s 1869 paper detailing his flawed test findings, the stink eye. Pointing out the same problem I saw when first encountering Magnan’s experiment — i.e., using wormwood oil rather than absinthe effectively negates the test as the essential oil contains significantly higher thujone levels than absinthe. So while France, Switzerland, and the USA (amongst others) lost their shirt over absinthism (which Magnan believed his test conclusively proved as a separate and worse disease than standard alcoholism) and the fiends the green fairy purportedly created.…This scientific side-eye damped the alarm over absinthism in the UK and is considered one of the main reasons Parliament dismissed the idea of banning the Green Fairy out of hand.

It also doesn’t hurt that absinthe never came anywhere close to supplanting Gin, Irish Whiskey, Single Malt, or Welsh Whisky in the hearts of British Isles imbibers. Otherwise, British distillers might have found themselves tempted to join forces with French vintners in their smear campaign against absinthe.

In any case, while the UK never banned absinthe, it doesn’t mean those who enjoyed the odd Frappe or Corpse Reviver at their local pub could do so. Unfortunately, when the Swiss and French bans landed, distilleries in both countries either switched production to a less contentious product or closed up shop. So, whilst the UK patrons could order a Sazerac or a Death in the Afternoon, most bartenders couldn’t shake or stir one up due to the lack of the key imported ingredient (according to the sources I read).

(Unless said pub owner, or their supplier, navigated the red tape around importing absinthe directly from Pernod’s distillery in Catalonia, Spain (where the liquor was never prohibited) until it closed in the 1960s. Or someone working in this theoretical pub somehow cultivated a connection to a Swiss home brewer. Despite the ban, Swiss fans with home distilling skills still produced it — though many switched their recipes to the clear version so they could pass their homemade efforts off as some other liquor if lawmen came a knocking.)

Then came WWI and WWII.

Under the hail of bombs, bullets, fear, and rationing, together with battlefield atrocities grabbing headlines and bans stymieing absinthe sales — news stories focused on crimes committed by “absinthe fiends” by and large fell away and without new fuel, the hullaballoo around absinthe slowly extinguished. Moreover, with people focusing on just surviving the day, for so many years, absinthe & its sinister reputation largely passed into urban legend.

In my estimation, this exit from the public’s day-to-day consciousness further rendered the “Absinthe made me do it!” solution unappealing to mystery writers. Since younger authors and audiences probably never tasted the anise flavored liquor or knew much about the brouhaha it caused. While mature authors and their readers could recall the attached lousy science and the ineffectualness of the absinthe defense in courts across Europe and the Americas.

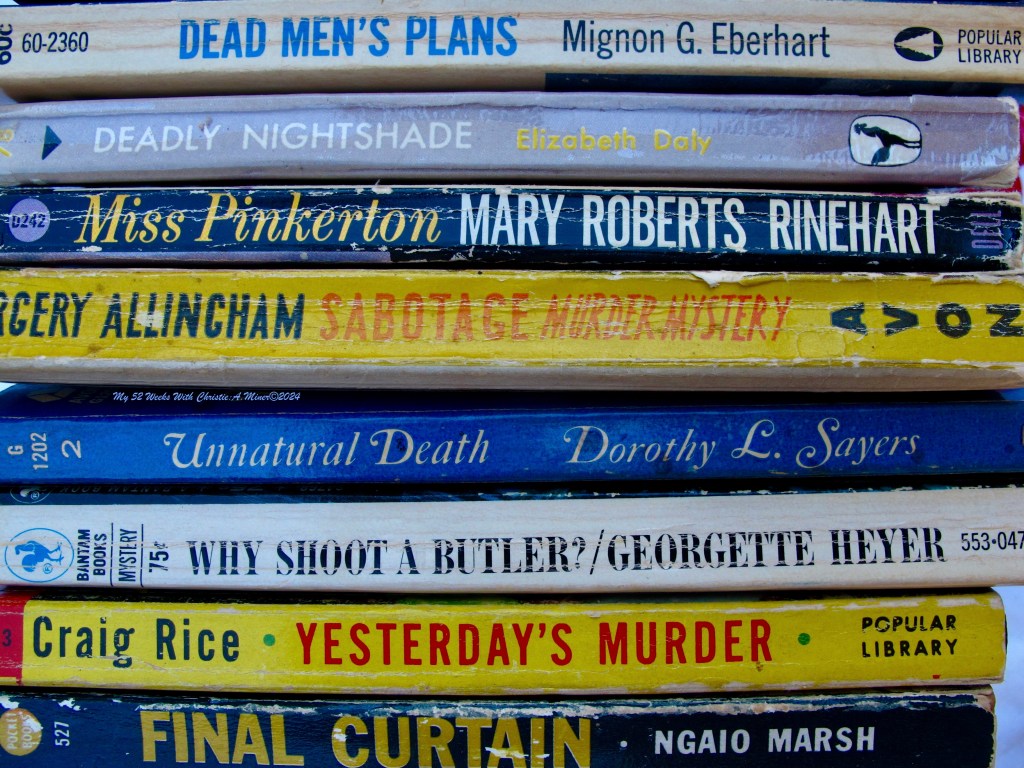

Okay, these titles probably don’t mention absinthe within…but it’s what I’ve got!

Perhaps all these aforementioned reasons account for the general absence of absinthe in mysteries penned by the Queens of Crime: Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh, and Dorothy L. Sayers; The American Queens of Crime: Elizabeth Daly, Craig Rice, Mary Roberts Rinehart, and Phoebe Atwood Taylor; Plus: Georgette Heyer, Josephine Tey, and Patricia Wentworth. In this pantheon of titans, only three (I can recall off the top of my head) chose to employ absinthe in any of their stories.

Agatha Christie used absinthe in the 1926 Mr. Harley Quin short story The Soul of the Croupier to quickly flesh out the deterioration of a promising future due in part to absinthe’s influence. Similarly, Georgette Heyer employed absinthe in her 1934 novel The Unfinished Clue. Evoking the memory of the hedonistic existence and excess of turn-of-the-century artists to quickly sketch out a similar sort of character. And Craig Rice mentions the liquor in Headed For A Hearse as one of her characters is battling an absinthe inspired hangover with a plate of eggs (I believe).*

The relegation of absinthe to a piffling plot device by these Mistresses of Mystery, I think, struck the death knell of the “Absinthe made me do it!” solution before it ever had a chance to take off as a trope. Furthermore, the sheer dominance of these women’s works during the Golden Age of Detective Fiction (together with the lasting influence they still enjoy within the genre) played a significant role in perpetuating absinthe’s role as a bit player in plots.

And with heat now wafting from each vent of our house, repairmen on their way, and our cash reserves depleted — I bid adieu to another home repair inspired question until next November.

(But hopefully not.)

*If I failed to mention a reference (as I am not infallible, nor have I read the complete bibliography of each authoress — yet), please be nice if you wish to point out an omission.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.