The Final Chapter: The Elephant in the Room

Much like Agatha Christie’s mysteries, I’m not going to give a play-by-play of Angele’s trial. Not only because it would take at least another four posts to do it justice (pun intended). But on account of the language ap I used to translate French newspapers, at one point, attempted to convince me an avocado played a critical role in Angele’s case.

An avocado.

I feel completely confident in stating Angele Laval’s case never hinged on a large green berry.

The alligator pear notwithstanding, I do know Mr. Victor Filliol, Angele’s lawyer, did his level best by her. Quickly realizing that Angele’s chances of receiving a fair trial in Tulle were narrower than the width of a hair, he looked into changing the trial’s venue. Unfortunately, there wasn’t a city, town, or hamlet in France untouched by the coverage of Tulle’s plague of poison pen letters. However, since she wouldn’t be facing a jury of Tulle citizens, he quietly abandoned this idea. Next, Mr. Filliol sought to bar the residents of Tulle from the courtroom, citing the fact the trial would necessitate the airing of sensitive material contained within the poison pen letters. The side benefits of this request are obvious: Not only would it mitigate, even if only slightly, the influence Tulle’s populace would enjoy on the officials deciding Angele’s fate. It would also spare Angele from facing a sea of openly hostile faces, day in and day out.

His request was denied.

On the opening day of her trial, December 4, 1922, the citizenry of Tulle demonstrated the wisdom of Mr. Filliol’s request. Masses of people gathered outside the courthouse. They packed staircases. Crowded the courtroom’s gallery. While generally making their belief in Angele’s guilt crystal clear.

For her part, Angele did her best to ignore the seething courtroom. The fact Angle wore the trappings of deep mourning — an ensemble of unrelieved black she augmented with a matching mantilla covering her hair and a dark fur muff that hid her hands — cut zero ice with the vocal throng scrutinizing her every move.

Angele Laval is the woman closest to the pic, her Aunt is next to her and sat with her throughout the trial. The other photos are of: The Courtroom, Tulle’s courthouse, and the people waiting outside.

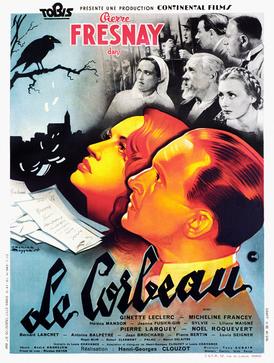

This habit of grief, which Angele wore for the whole of her trial, led a reporter from Le Matin (a newspaper) to describe Angele as — “….a poor bird that has folded its wings.” The reporter continued reinforcing this avian imagery throughout his coverage of Angele’s trial. His impression, repeated periodically in subsequent accounts, laid relatively dormant until 1943 — when Henri-Georges Clouzot’s movie Le Corbeau hit cinemas. Very loosely based on Tulle’s poison pen campaign twenty years earlier, the filmmaker expanded on the avian imagery by changing Angele’s nom de plume from Tiger’s Eye to The Raven — a purported harbinger of ill-tidings.

Now this association of ravens with poison pen letters & writers might have died on the vine if: A) The film wasn’t excellent. B) Experts didn’t consider Le Corbeau the first film noir film before film noir was actually a thing. And C) The film and its director didn’t cause such a lasting stir.

Apparently, Clouzot secured financing for Le Corbeau from a Nazi funded film company…….during WWII……while France was occupied by the Third Reich. Adding fuel to the fire, during France’s occupation, (apparently) it was common for people to write anonymous letters denouncing their neighbors (generally for helping or siding with the Nazis). So rather than seeing Le Corbeau as a true-crime-inspired story, the French Resistance saw it as a cautionary tale meant to frighten French citizens. Others saw the stark noir portrayal of a provincial town in the grips of hysteria as an unflattering portrait. Unsurprisingly, Le Corbeau was banned soon after its release (in point of fact, the film was officially suppressed until 1969) for “vilifying the French people”.

Despite this, the film was a hit.

After the liberation of France in 1944-1945, Clouzot was tried as a German collaborator — whereupon the courts imposed a lifetime ban from film sets and from owning a motion picture camera. However, thanks to several notable artists who spoke on his behalf (one of whom was Jean-Paul Sartre), his lifetime ban was reduced to two years (until 1947).

Fun Fact: Otto Preminger remade Le Corbeau for American audiences in 1951 and renamed the film The 13th Letter.

All of the above is a long-winded explanation of how, in France, poison pen writers came to be known as ravens, including Angele — who’s now referred to as The Raven of Tulle rather than by her chosen pen name, Tiger’s Eye.

Speaking of Angele, let’s get back to her trial.

Amongst the twenty-three witnesses called to testify — several were people who received, found, or saw the poison pen letters around Tulle. Whilst establishing that no one person could’ve left all the noxious notes all over Tulle — they also made it clear no one ever witnessed Angele delivering a single poison pen letter. As for the partially written letter the priest espied on a table during a visit with Angele and her mother Marie-Louise — Mr. Filliol didn’t deny what he saw. Instead, they claimed Angele occasionally drew wildly unflattering caricatures of her neighbors for her own enjoyment.

An explanation that sounds so ridiculous it might be true, but it’s hard to swallow.

Top Row: The comparison of letters from the Poison Pen Letters to Angele’s writing.

Bottom Row: The experts & Mr. Filliol debating if Angele wrote the letters.

The main event of Angele’s trial came when Mr. Filliol locked horns with Dr. Locard. The defense found not one but two graphologists willing to contradict Dr. Locard’s findings. Mr. Filliol then accused Dr. Locard of allowing the highly charged atmosphere of Tulle and Angele’s strange behavior at the time of her assessment to influence his conclusions. Angele’s defense contended that rather than carrying out a rigorous examination, using techniques he helped pioneer, Dr. Locard merely eyeballed Angele’s handwriting exemplar next to a Tiger’s Eye letter — then declared her guilt.

As tactics go, this was a sound strategy. Unfortunately, Mr. Filliol couldn’t present a convincing alternative explanation to account for Angele’s bizarre behavior during her handwriting examination.

A Feature of Interest: Thirty years after testifying in Angele Laval’s case, Dr. Locard abandoned graphology, citing its inexactness as a science. Apparently, in 1945 he attributed a series of anonymous letters to a woman, who was subsequently sentenced to a lifetime of hard labor, only to discover (in 1956) she was not the author.

Despite Mr. Filliol’s hard work, on December 20, 1922, the Judge delivered a sixty-page, scathing judgment against Angele….Though she wasn’t present to hear her fate firsthand. Someone sagely convinced Angele to stay away from the courthouse on the day of her sentencing. The move proved sound as a mob, several hundred strong, stood outside the building feverishly anticipating Angele’s trip to the guillotine for her role in August Gilbert’s death.

Sorta Fun Fact?: Before abolishing the death penalty in 1981, France was the last country to use a guillotine for a state-sanctioned murder. When in 1977, convicted murderer Hamida Djandoubi was executed in Marseille.

Whilst the residents of Tulle were ready to sentence her to death, those with the power to send Angele to meet her maker had other ideas.

Recall Angele’s enforced visit to Limoges’s lunatic asylum? During her eight months inside, alienists (an outdated term for psychiatrists) evaluated her mental health. They concluded that while Angele knew right from wrong and could be held responsible for her actions, she teetered on the brink of madness.

In point of fact, the alienists did not wish to release Angele from the asylum at all — citing, amongst other things, her frequently expressed desire to kill herself, the censure she suffered at the hands of Tulle citizens, and the resulting isolation. However, after Angele’s general practitioner testified that she’d never been prone to ‘hysterical’ behavior and Angele described the alienist’s multiple attempts to extract a confession via hypnotism as well as the numerous occasions they’d forced her to wear a straitjacket — the Judge ordered Angele’s immediate release (just a few days prior to the official start of her trial).

Though they lost that battle, the alienists won the war.

During their testimony, in which an alienist presented what he thought was tantamount to a confession from Angele (though to be clear, it was not an actual confession) — he also advocated treatment over incarceration in Angele’s case. The recommendation, when combined with the sentencing guidelines for public defamation and the first offender act — resulted in Angele receiving a suspended sentence of one month in prison, plus a one-hundred franc fine for defamation and another two hundred francs in compensation to her victims. Angele, who’d maintained her innocence before, during, and after her trial, paid little heed to the lenient sentence. She appealed the next year…..and lost.

The citizenry of Tulle, deprived of the justice and spectacle they thought they deserved, imposed their own life sentence on Angele. Not only did they continue to shun and shout curses at her whenever she dared to leave the house — they made it impossible for her to find work, marry, or make friends. Her notoriety, thanks to the press who splashed her face all over the papers, made it equally impossible for her to start over somewhere else in France. Angele spent the rest of her life as a recluse with the only people who believed in her — her brother Jean and his family.

Angele Laval died forty-four years after her appeal on November 16, 1967.

What of the other Poison Pen writers who rode Tiger’s Eye’s coattails? Despite delivering 100 to 200 noxious notes above and beyond the 110 attributed to Angele — no one else (so far as I can tell) was ever brought to account. The last known anonymous letter of this caustic campaign was delivered to Mr. Filliol. Slipped into his briefcase during Angele’s trial, he reported it immediately to the court — as most eyes were riveted on Angele and she sat in front of Mr. Filliol’s desk — he swore (and I believe him) that Angele never had the opportunity to place it inside.

Perhaps this factored into Angele’s overall light sentence.

The question is: Did everyone get it wrong? Was Angele really innocent?

Angele’s brother Jean is the gentleman with the x below his shoes.

Not only were there multiple other poison pen writers who got away scot-free. There was one person connected to the prefecture, Mouray, Angele, and Marie-Louise, who owned a genuine motive for starting a poison pen campaign — Angele’s brother Jean. According to all accounts, his professional envy of Mouray was well known within the prefecture, and if Dr. Locard’s report correctly attributed an undisclosed number of Tiger’s Eye letters to Marie-Louise….Could the two have worked together?

Did they start writing poison pen letters together, hoping to crush Angele’s infatuation with Mouray? Did they continue with the intention of pinning the blame on Marie-Antoinette and forcing Mouray to resign in disgrace? There was no love lost between the two men. Jean was perfectly positioned to hear salacious bits of gossip about the great and good of Tulle. As a Captain in the prefecture, Jean could’ve easily planted the early letters inside the prefecture, and his mother had plenty of time to sprinkle the later letters all around Tulle.

Did Dr. Locard mistake Marie- Louise’s hand for Angele’s?

When she realized Angele would shoulder the blame instead of her, did Marie-Louise convince Angele to commit suicide rather than admit to what she’d done? Is that why Jean supported and sheltered his sister for the rest of her life? Guilt?

Convoluted as it sounds, it’s possible — just not probable. Like everyone else one hundred years ago, I cannot overlook Angele’s peculiar behavior during Dr. Locard’s writing examination. Why take so much time writing one line? Why repeatedly retouch them if you don’t have something to hide?

Plus, much like Miss Marple in The Moving Finger — I find love, even frustrated love, a much stronger motive than envy.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.