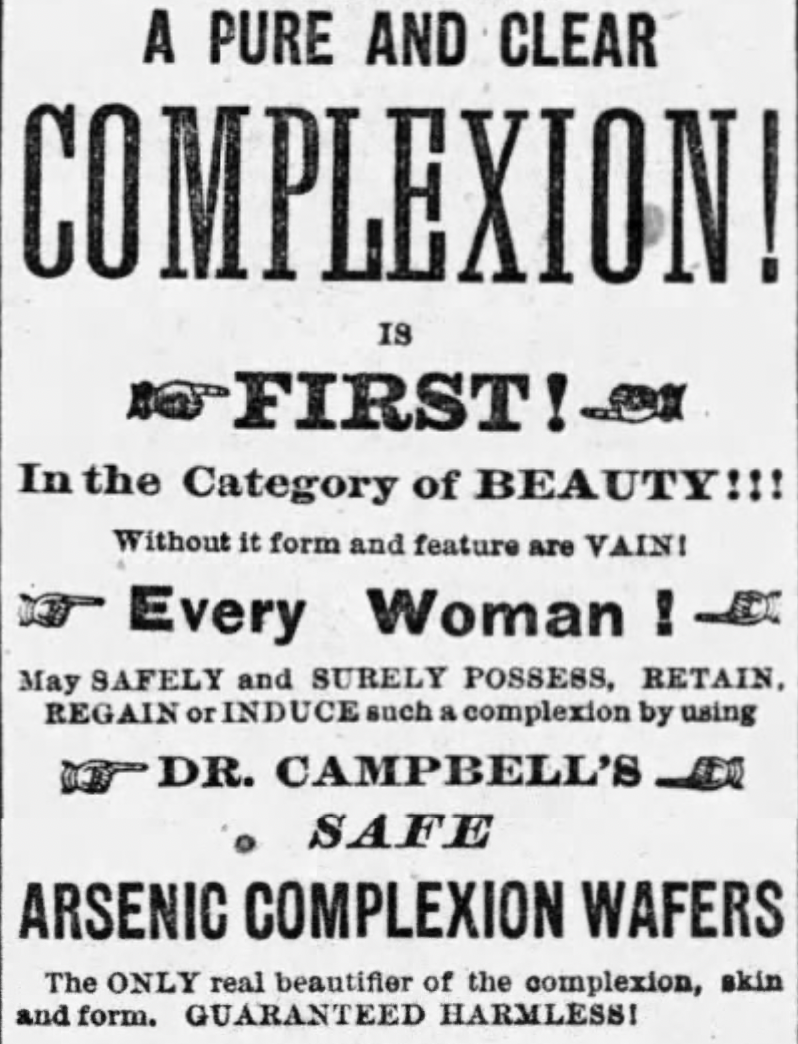

After the state recalled Dr. Miller and a Coroner’s physician to the stand, both of whom swore neither Alma nor Arthur suffered from any disease that would require treatment from an arsenic based medicine (endeavoring to rebut Sadie Ray and Louisa Lindloff’s insistence that the pair had), the state and defense made their closing arguments then rested their collective cases.

At 3:45 pm, on November 5, 1912, the jury started deliberating Louisa Lindloff’s future.

Whilst they did so, Louisa laughed and gossiped with Sadie Ray and other friends in the vacated jury box. Reporters sat in the gallery and started writing yet more copy about how a woman, even a mass murderer, couldn’t get convicted by a Cook County jury. A sentiment most spectators still sitting in the courtroom echoed, much to the despair of the Assistant States Attorneys.

Though the jury created a stir when the bailiffs escorted them to dinner at the Alexandra Hotel and again when they returned at 7:30pm — it wasn’t until a knock sounded on the jury room door at 9:15pm that the butterflies in everyone’s stomachs took flight. After shuffling back into their seats, the jury foreman rose and declared Louisa Lindloff guilty of murdering her son, Arthur Graunke, and sentenced her to twenty-five years in prison.

Seems the jury unanimously agreed on Louisa’s guilt straight away. What took the next five-ish hours to settle was Louisa’s punishment: On the jury’s first ballot – 5 wanted life in prison and 7 wanted Louisa to hang. On the second ballot – 5 voted for life in prison and 7 switched to a term of 40 years. Finally, on the third ballot – the twelve men compromised and settled on 25 years.

The resulting headlines touted Louisa as the first woman convicted by a Cook County jury in three years.

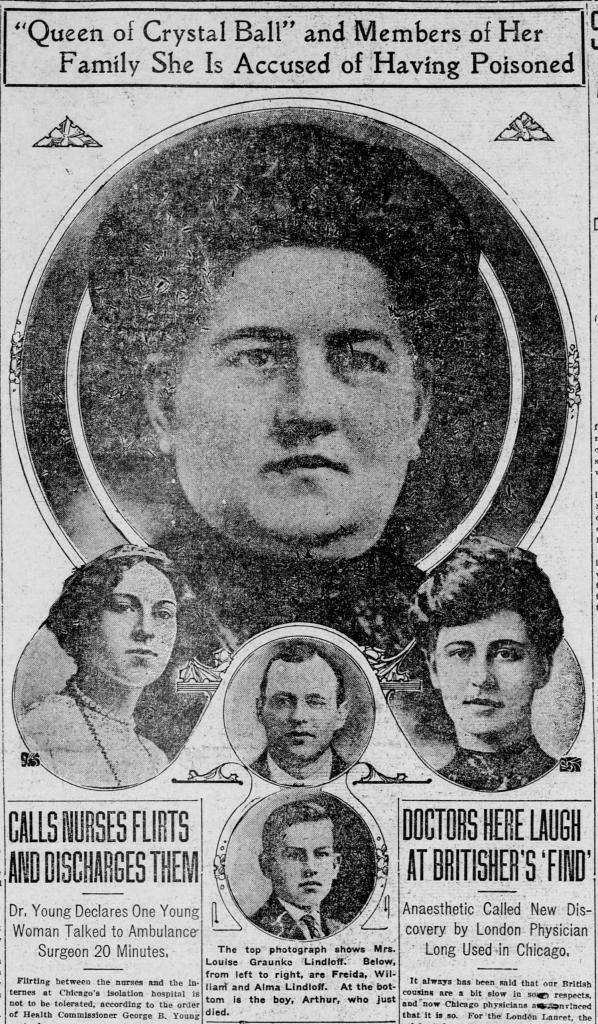

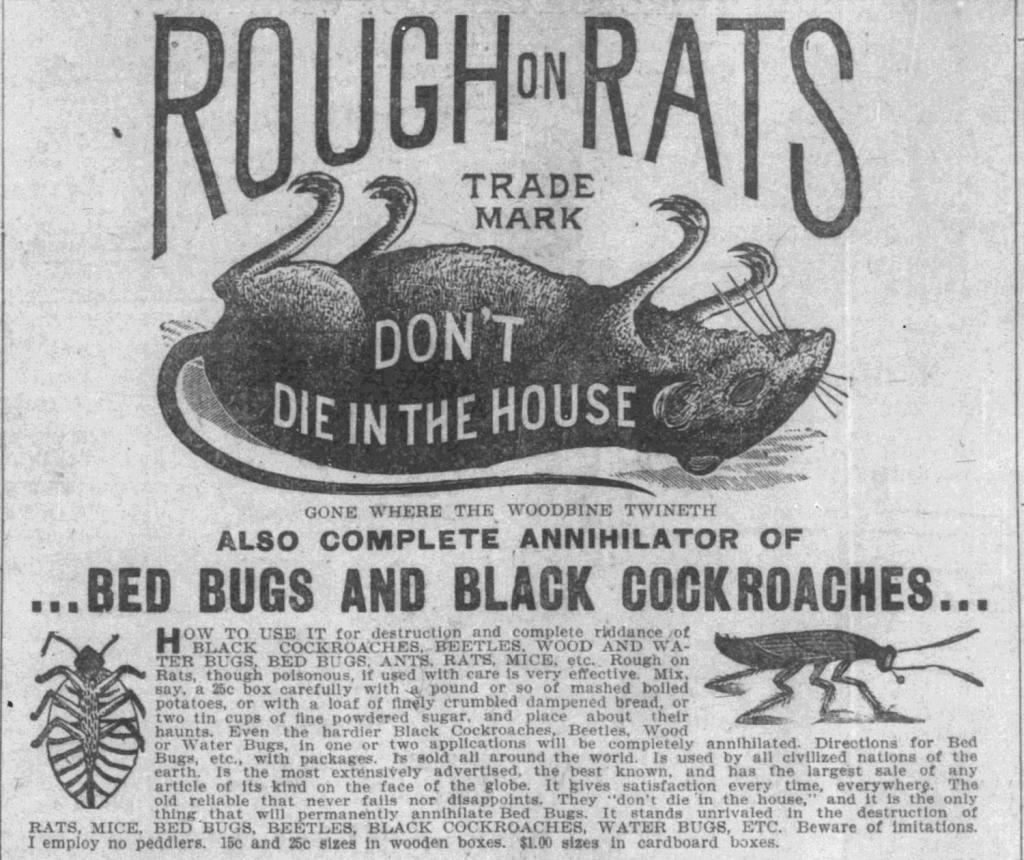

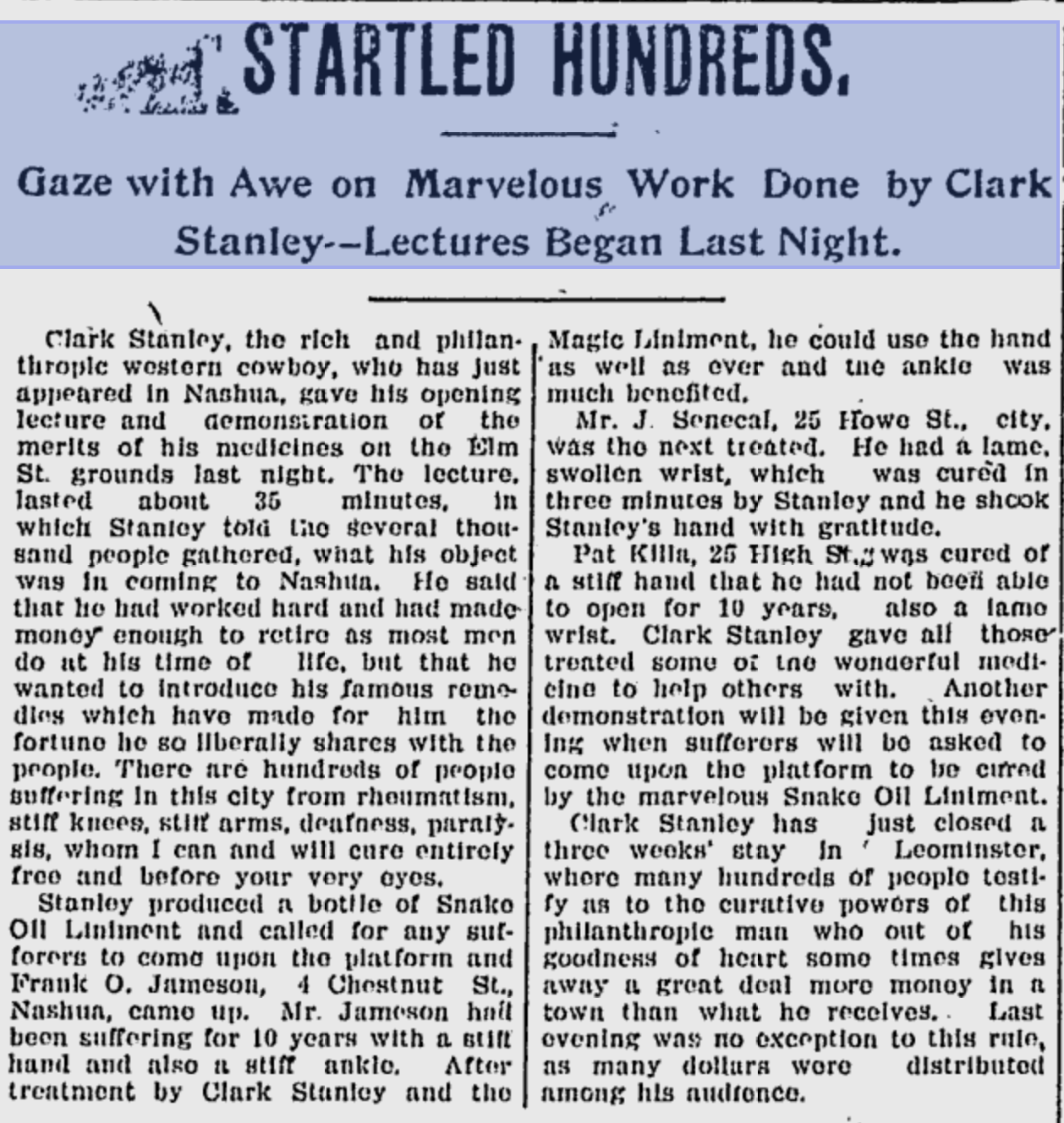

A typical article about Lulu’s crime.

A bulletin that highlights the casual racism of the day.

For you see, only one month before, in the very same judge’s courtroom, Lulu Blackwell was sentenced to thirty-five years in prison for manslaughter. The only difference? Both the Lulu and the victim, Charles Vaughn, were black. A fact which apparently made a difference to the white newspaper editors of Chicago. As not only was there significantly less coverage of Lulu’s crime and trial (in the papers I’ve got access to), when her name was mentioned either during the scant trial coverage or on the lists of women arrested for murder, most papers felt the need to point out Lulu’s skin color, and none (I found) mentioned Lulu’s stretch inside Joliet Prison being longer than Louisa’s — for a lesser charge.

Although there’s a distinct lack of copy on both the murders committed by black women and the subsequent acquittals they won during this stretch of time in Cook County, I did find a few — like Belle Beasley. Who, after five minutes of deliberation, was acquitted. Despite being found standing over her dead husband with a literal smoking gun in one hand and newspaper clippings of other women cleared of murder by Cook County juries clutched in the other.

All that being said, one of the biggest issues for Lulu’s defense was she brought a gun with her to 3212 Dearborn Street. Beyond all the typical problems associated with shooting someone in a fit of jealousy, before their house, on a public sidewalk, in front of witnesses. (Charles was planning to marry another.) By lugging the firearm to the confrontation, Lulu gave the impression, real or not, that some level of plotting went into the act. Making it that much more challenging to convince a jury that Lulu acted in either ‘the heat of the moment,’ self-defense, or needed protection under Chicago’s ‘unwritten law.’

An identical whisper of premeditation would haunt and ultimately help convict Vera Trepagnier at trial seven years later.

Then, there were the barks of laughter Lulu reportedly let loose during the testimony of the witnesses called against her. Remember, the men called to serve on Cook County juries only wanted to see overt displays of contrition, regret, and/or remorse on the faces of the women they were judging. Hence why, Billy Flynn became annoyed with Roxie (in the 2002 film adaptation of Chicago) when reporters asked during We Both Reached for the Gun if she was sorry for murdering her boyfriend and she replied, “Are you kidding?” Had Roxie continued to appear unrepentant, as she nearly did, until a state-sanctioned murder radically changed her tune — ten-to-one, she would’ve found herself facing a length of rope.

This lack of visible contrition also damned Katherine Baluk (aka Kitty Malm, aka Tiger Girl) to life in prison in 1924, for possibly shooting a security guard to death. She was also the real life inspiration for the character Go-to-Hell-Kitty in Chicago (the musical).

Though the reasons behind the jury’s decision to find Lulu guilty are only educated guesses — what isn’t — is the utter shock she displayed upon hearing the word ‘guilty’ ring out in the courtroom. An emotion Louisa would mirror thirty days later after the same exact verdict reached her ears.

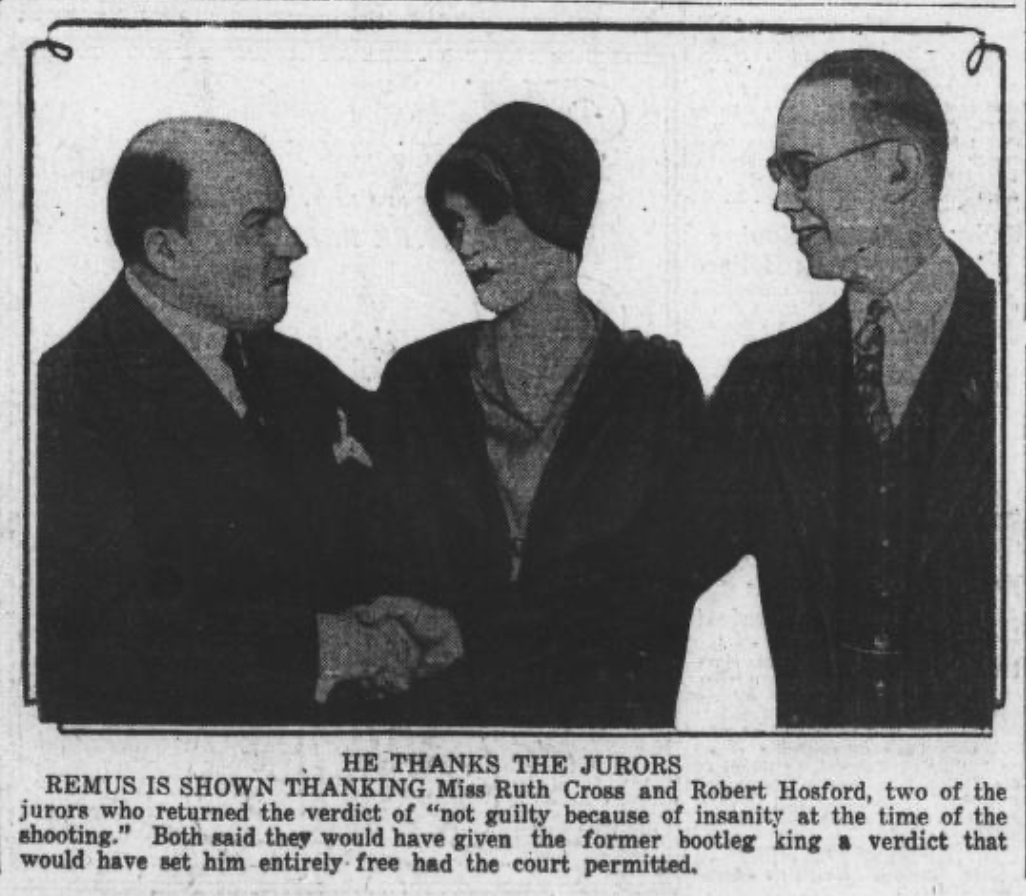

While George Remus lept to his feet and motioned for a new trial — Louisa sat stock still. Only after she was led from the courtroom did she break down. After recovering from a fainting spell, Louisa wept and gave reporters this quote: “There is no justice here…Those that are guilty are turned loose and those who are innocent get the worst of it. I will show my innocence before I am through. It will only be a question of time. I did not kill my boy or any others. I am innocent, as God is my witness.”

Interestingly enough, unlike Isabella Nitti and Hilda Exlund, who blamed their conviction on their looks, Louisa didn’t. She blamed a different source: “The spirits lied to me—they lied—they told me I would be acquitted. They promised I should be free—and here I am, convicted. Why have I believed the spirits—they lie.” Though Louisa’s disillusionment in the spirit world quickly faded and new predictions of her imminent release followed — the press, her fellow spiritualists, and the public had already moved on.

Judge Windes presided over Hilda Exlund, Lulu Blackwell, & Louisa Lindloff’s trials. All of whom bucked the trend and were convicted of murder or manslaughter.

A circumstance that may have changed if Louisa’s appeal for a new trial came to fruition. And thanks to Judge Windes’ decision to allow the introduction of Julius, John Otto, Frieda, William, and Alma’s deaths into evidence — there was an excellent chance the Illinois Supreme Court would’ve approved this appeal.

Granted, the other deaths and their connected life insurance policies/payouts created a compelling pattern. However, Louisa was never formally accused of, arrested for, or tried for any death other than Arthur’s. Meaning they shouldn’t have been presented as evidence to the jury. An argument Chief Justice Carter of the Illinois Supreme Court seemed to nominally agree with, as on March 15, 1913, he issued a ‘writ of supersedeas.’ Allowing Louisa to move back to Cook County Jail’s Murderess Row while waiting for the Supreme Court to hear her appeal.

However, we will never know how the Justices would’ve ultimately ruled.

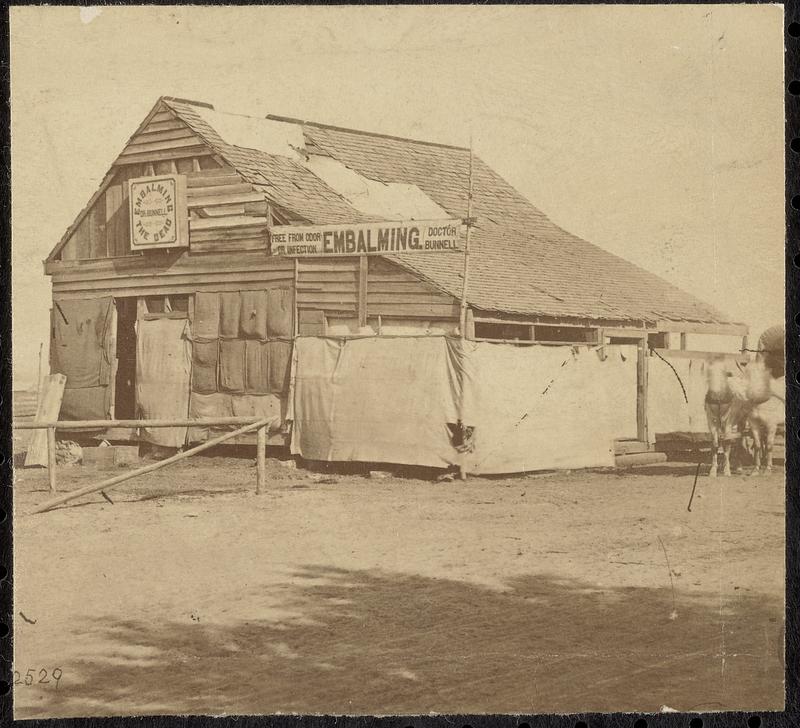

From L to R : A) The entrance to the Woman’s Prison at Joliet B) Women’s Prison Cell Block C) Two inmates making rugs D) Woman’s Dining Hall E) Female prisoners did all the laundry for themselves & the men’s prison here E) Prison Cemetery, though Louisa wasn’t buried here Lulu may have — though its unclear if the female & male inmates were buried together

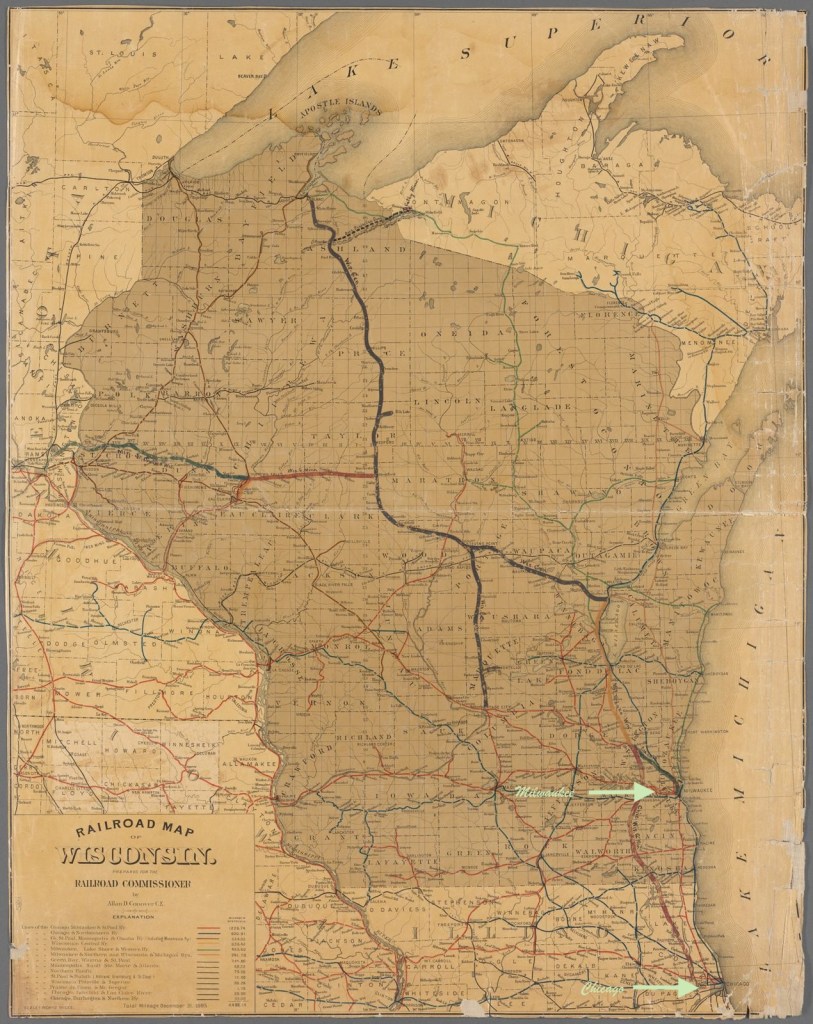

On March 15, 1914, Louisa Lindloff died of intestinal cancer while waiting for her date with the Supreme Court. One of her last published quotes was, “I have nothing to say — I am happy to die.” (Sadly, Lulu Blackwell preceded Louisa beyond the pearly gates by eight months, dying of septicemia inside Joliet State Prison on July 13, 1913. The only note of her death I found was a single line in an annual report published by the Illinois prison system.)

Supreme Court appeal and protestations notwithstanding — what do I think? “There was Mrs. Green, you know, she buried five children — and every one of them insured. Well, naturally, one began to get suspicious.” Though this Miss Marple quote from The Bloodstained Pavement was written about sixteen years after Louisa Lindloff’s 1912 conviction and undoubtedly about a different poisoner, I think it neatly sums up the spirit behind Louisa’s crimes.

IMHO, it feels far too coincidental that: A) Julius Graunke & Charles Lipchow died in August, a year and three days apart from one another. B) William Lindloff & Alma Graunke also died in August, a year and a day apart from one another C) Frieda & Arthur Graunke died four years and two days apart from each other in June. John Otto Lindloff, who died in October, is the only outlier to this pattern. However, if Louisa worried he and Frieda would move beyond the easy reach of her box of Rough on Rats after they married — this might explain why she didn’t wait.

Together with the thousands of dollars, Louisa earned each time she buried someone? Plus, the lies she told the police upon discovering the insurance policies on Arthur’s life? It’s compelling, even without Sadie Ray’s uneven account of Louisa trying to slot her death into the timeline. Over and above that, Louisa’s excuse that cucumbers led to Arthur’s death is just flat ridiculous.

In other words, yes, I think she did it.

On the topic of Louisa’s Victims: After the trial concluded, Chicago Police Captain Baer went on record with his belief that on top of murdering Arthur, the rest of her immediate family, Charles Lipchow, and Eugenie Clavett — he’d uncovered evidence that Louisa had murdered fifteen more people, including a five-month-old infant. (Not to mention the countless animals witnesses swore Louisa killed while experimenting with different poisons.)

Assuming his intelligence was correct, that would bring the grand total of murders ascribed to Louisa to 23.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.