“He doctored the hundreds and thousands…”

Upon encountering this solution for the first time in the Miss Marple short story, The Tuesday Night Club, I was left baffled. Why? Because up until that moment, I’d never encountered hundred-and-thousands before.

Or so I thought.

Turns out I knew exactly what they were only by a different name: Sprinkles.

Since that day, I’ve learned these tiny confections are much like Shakespearian roses — tasting just as sweet whether they are called hundreds-and-thousands, jimmies, jazzies, vermicelli, nonpareils, pearls, shots, or snowies. Though there are minor variations amongst them, to my mind, they all fall under the broad umbrella of sprinkles.

Okay, fine.

Satisfied with finding the answer to my question, I moved on to the next Miss Marple mystery. Yet, upon subsequent reads, beyond making me giggle at my younger self, something about “He doctored the hundreds and thousands…” still nagged me. Something I couldn’t quite put my finger on until I started baking cookies every Thursday to share with Seattle Mystery Bookshop patrons on Fridays.

How did this nefarious fictional husband manage to “doctor” those hundreds-and-thousands?

At first, I theorized he shook them in a jar with the poisonous powder. The only problem? The baddie intended to do away with his wife straightaway, and I’m not so sure this dusting would impart enough arsenic to achieve his hideous objective. (Nor is this something I am going to fiddle around with to find out. There’s a limit to my dedication to this blog.)

Moreover, simply tossing the sprinkles around in an arsenic based powder (like so much lettuce in dressing) would leave behind a visual clue. Which could be mistaken for some sort of spoilage. Leading the victim to leave her desert uneaten and her husband’s wicked plan unfulfilled.

Neither could this villain simply soak the sprinkles in an arsenic solution to impart the element’s death-dealing properties. As sprinkles, being composed primarily of sugar, would melt. Knowledge my much shorter self acquired by watching a generous measure of nonpareils melt into my ice cream nearly every Saturday evening at my grandparents’ house.

So, how did the murderer do it?

Since I’ve never lived in a world where sprinkles, snowies, hundreds-and-thousands, jimmies, jazzies, and nonpareils haven’t been available on grocery store shelves in tubs, tubes, and cartons. It took me far longer than it should’ve to arrive at a solution.

Or, at least, an answer that makes sense to me.

Then, a few months back, during a commercial break in The Great Canadian Baking Show, several of the former popular/winning contestants popped back onto the screen, extolling the virtues of a particular food product by demonstrating its versatility. Witnessing one of the former bakers piping tidy rows of raw sprinkles onto baking sheets caused my little grey cells to sit up and sing.

This was how the foul spouse “…doctored the hundreds and thousands…”

He made his own.

Theory firmly lodged amongst the folds of my brain, I did a bit of sleuthing to see if this idea was even remotely possible. Whereupon I learned the machine-made sprinkles I love to put on anything, and everything are just over one hundred years old.

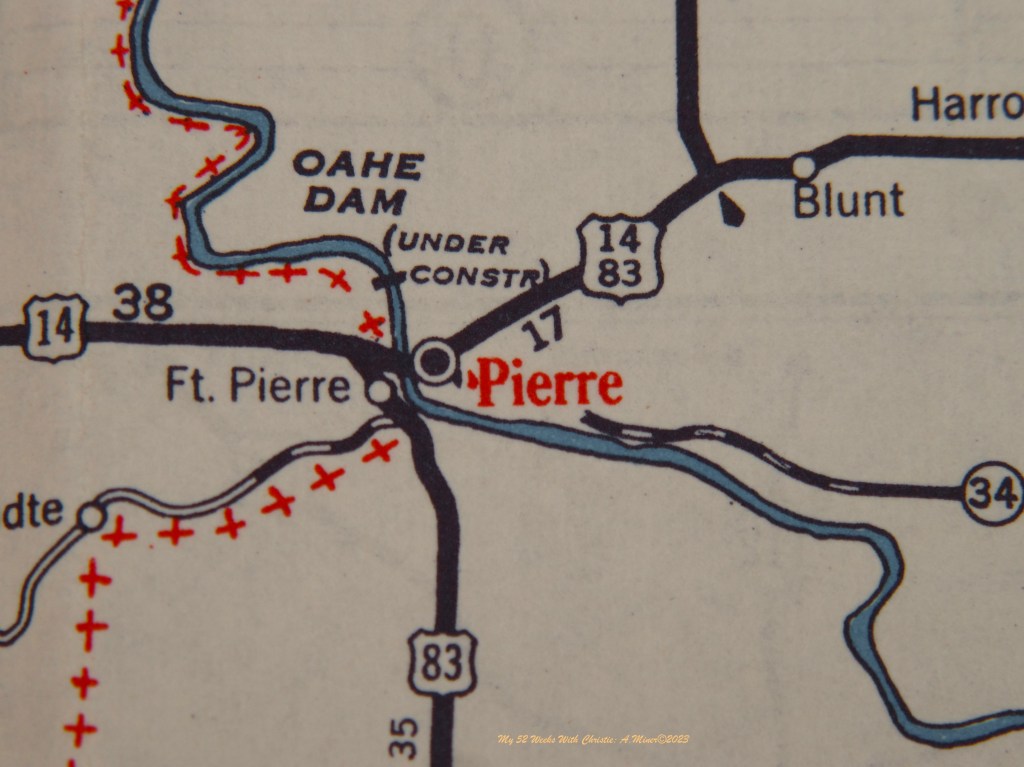

Newspaper adverts from 1921-1923 for sprinkles.

According to Wikipedia and corroborated by advertisements I located, chocolate sprinkles started becoming commercially available across the U.S. around 1921. Seven years after, a pair of Dutch candy companies pioneered a similar product. Which, unlike many of their American counterparts, actually contained real chocolate. (Though how fast these manufactured petite sweets traveled across the English Channel and into the UK, I don’t know.)

Although this technological advent is fairly new (in geologic terms), homemade sprinkles date back several centuries. Apparently, there’s several French pastry recipe going back to the seventeenth century which gives bakers the option of topping their treats with nonpareils or sanding sugar. Even more exciting, thanks to Michigan State University’s Feeding America: The Historic American Cookbook Project, there’s an indexable cookbook with a recipe for nonpareils dating back to 1864!

This quick and dirty timeline, when paired with the fact that Agatha Christie published The Tuesday Night Club in 1927, shows us that Agatha Christie, Miss Marple, and the killer all inhabited a world before mass-produced sprinkles stepped into the limelight. More importantly, the knowledge of how to make snowies at home hadn’t been shunted off to the periphery of baking — yet. (Where these recipes lingered for nearly a century until Covid lockdowns gave people time to explore the margins of baking again.)

A modern take of a traditional trifle. The photo’s from Unsplash.

Okay, fine, he made his own sprinkles.

But how did this villain ensure his unsuspecting wife would eat a lethal amount of arsenic via these crunchy bits of formed sugar? Mind you, this is only an educated guess, but I suspect he substituted rat poison for a portion of the powdered sugar and swapped the clean water for some he’d adulterated with flypaper. Then, he instructed his accomplice to use a heavy hand when applying the poisoned pearls to the top of the trifle.

(Please, don’t do this.)

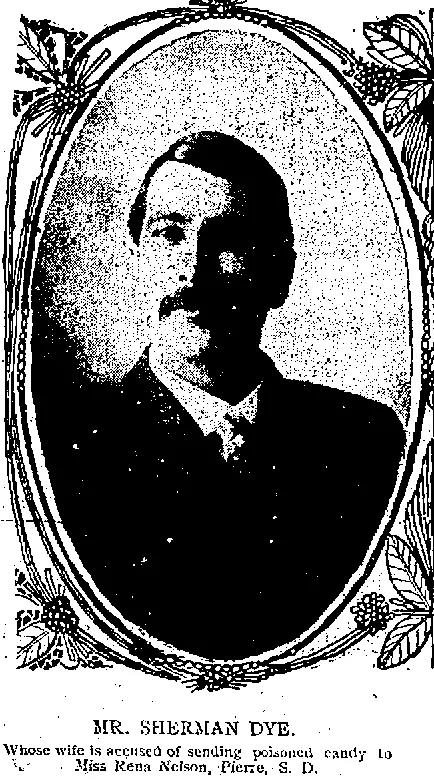

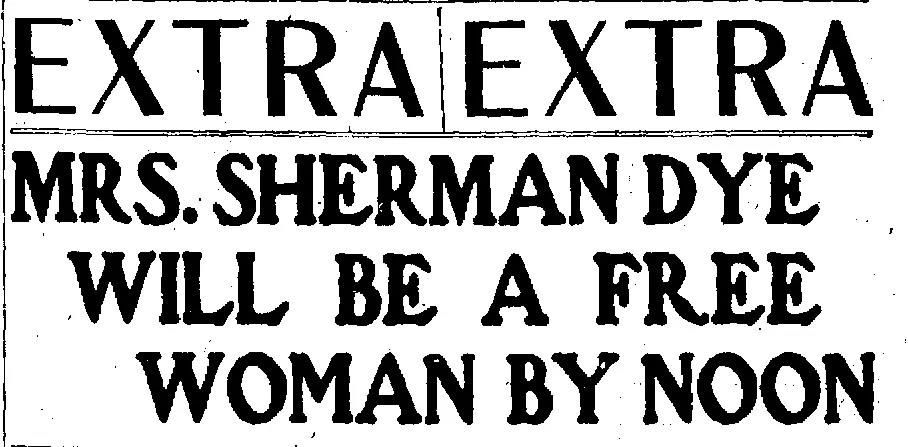

A Rough on Rats advert which gives instructions on how to kill rats that, sadly, work equally well on humans.

Remember, this murder took place in 1926-1927 when manufacturers of rodenticides and insecticides happily embraced arsenic as their active ingredient. Despite the colorants producers added to their products, endeavoring to dissuade people from administering rat poison to their nearest and dearest, this fail-safe often fell short. In this fictional instance, so long as this diabolical husband stuck to making chocolate sprinkles, this “safety feature” was easily circumvented.

Above and beyond ensuring his wife’s untimely death, this murder-minded spouse accomplished several other feats by making his own hundreds-and-thousands. Recall that aforementioned accomplice? The effort this man took to “doctor” these sprinkles, more than likely, allowed him to manipulate his desperate (according to the text) younger lover/accomplice into carrying his heinous plan over the finish line.

In a — I did my part, now it’s your turn — kind of scenario.

Though I wonder: Did his female accomplice realize he was setting her up to take the fall? Because I bet dollars to doughnuts, this crooked husband could prove he never set foot in the kitchen the day that terrible trifle was served (and probably most others). Why would he? He had both a wife and a maid to take care of the canning, candy-making, and meals for him.

Next, by partaking of the tainted treat with his wife, he misdirected attention away from the nefariously designed arsenic ladened sprinkles and himself. A calculated risk that bought him a breath of deniability should his wife’s murder and its method come to light:

OMG, if I hadn’t scraped those hundreds-and-thousands of my portion, I would’ve followed my wife to the grave!/ I don’t care for their texture./ They were contaminated with arsenic, you say? How can that be? My wife always bought XYZ brand. Oh no! Has someone else died?/ They were handmade? You don’t say./ She said what? She‘s crazy! I never did anything to encourage her affections. I was a happily married man./ She says I made those hundred-and-thousands? How? I can’t even boil water!

And so on and so forth. Until…

It wasn’t I who sprinkled the hundreds-and-thousands on that damned trifle.

At least that’s how I imagine the murderer might have used the era’s everyday sexism as a smokescreen, why I believe he made chocolate sprinkles to complete his evil deed, and the method he used to “doctor” the hundreds and thousands in this classic Miss Marple mystery.

TO BE CLEAR: I’m not advocating weaponizing sprinkles. Murder is illegal, immoral, unethical, and frankly, a d**k move. So, please, please choose kindness over violence.

My 52 weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2025

You must be logged in to post a comment.