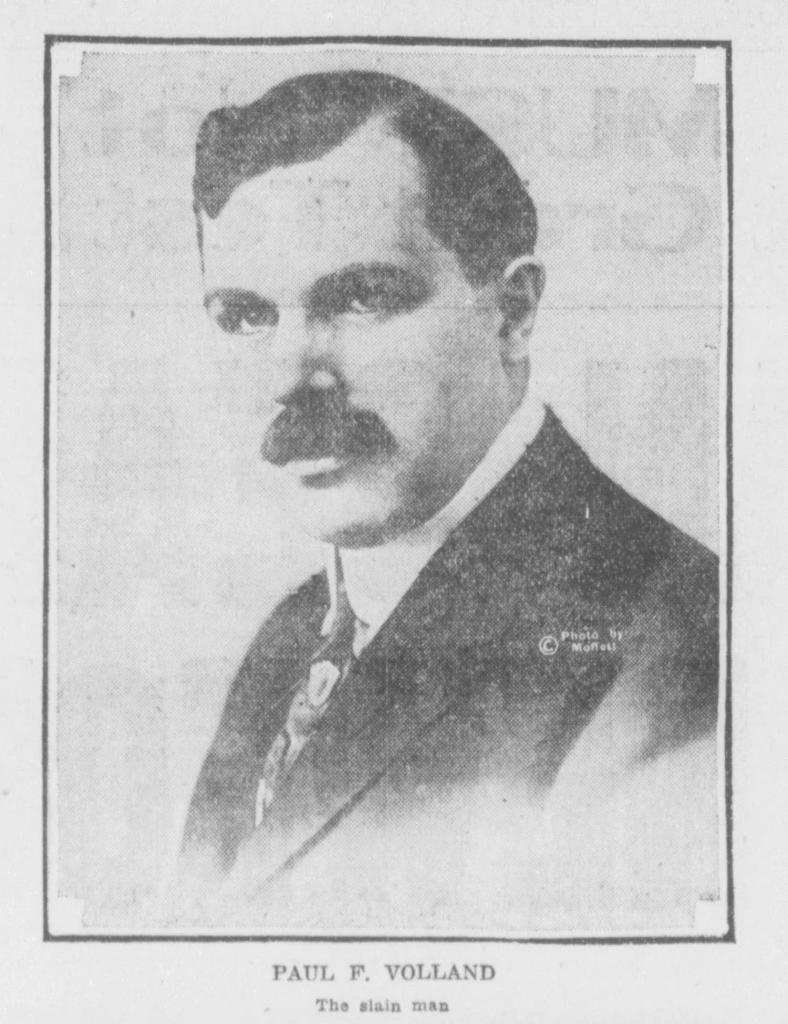

On May 6, 1919, the day after slaying Paul F. Volland, a Grand Jury charged Vera Trepagnier with his murder. What’s more, the twelve men refused to set bail, thereby sending sixty-year-old Vera off to the Cook County Jail to join the other women awaiting trial on its infamous Murderess Row. Nevertheless — despite the charge, the multiple witnesses placing her in the room when Volland died, handing Patrolman Patrick Durkin the murder weapon, and confessing to the crime — Vera wasn’t without a heaping helping of hope that she’d get away with murder.

Sounds mind-boggling, right? Hope, in the face of an apparent prosecutorial slam dunk.

Lists like this one, printed in 1914, were printed fairly frequently in papers across the country.

However, in the 12 years leading up to Paul F. Volland’s death, Cook County prosecutors only managed to convict 3 out of the 29 women put on trial for murder or manslaughter (according to the tallies routinely published in the papers). Which begs the question: How? Well, in studying Vera’s case, as well as yards and yards of newspaper columns covering the 29 women who preceded Vera into the courtroom (and a number who came after), a familiar refrain kept repeating itself.

And They Both Reached For The Gun

Variants of this line kept creeping up, pinging a distant and dormant earworm in the back of my brain. Unable to recall why it sounded so very, very familiar, I tapped the phrase into a search engine and immediately learned why it resonated.

Did you know the musical Chicago is loosely based on real murders and murderesses? Maurine Dallas Watkins, the play’s original author, based Chicago on two (in)famous criminal cases she covered during her eight-month stint with the Chicago Tribune in 1924. Beulah Annan, who shot her married lover in the back, served as the inspiration for Roxie Hart. Belva Gaertner, the muse for Velma Kelly, claimed to have no memory of shooting her married lover in her car after they’d spent several hours visiting bars, drinking, and listening to jazz. You will be unsurprised to learn both women were acquitted of the crimes.

The musical, created after Watkins’ death in 1969, does a great job of exposing the formula defense lawyers (generally, though not exclusively) followed to obtain acquittals for their female clients.

These were just some of the “glamorous” newspaper photos of the women who were eventually acquitted for murder/manslaughter in Cook County.

Step One: After committing the crime (of course), feed the media. Recall the newspaper headline that started me down this odd and twisting path: “Can A Beauty Be Convicted?” Admittedly, owning youth, good looks, and manners didn’t hurt their cause. However, what this story conveniently ignores (though the musical shows in aces) is the symbiotic relationship enjoyed with many, though not all, of these female killers and the press.

By answering questions shouted at them on the courthouse steps and granting interviews, these women helped improve the paper’s circulation numbers whilst priming potential members of their juries before ever stepping into the courtroom.

Thereby explaining why Vera, who declined to testify before the Grand Jury in her own defense, gave a series of interviews to reporters hours after joining Murderess Row. By laying out her slow spiral into poverty after losing her fortune, home, and husband while making sure to mention her altruistic plans for the $5,000 and/or the painting, Vera noticeably softened the tone of the subsequent coverage.

More importantly, by concentrating on her life story and the lopsided deal she unwittingly struck, Vera could obliquely portray Paul F. Volland as a rich man willing to use his power and position to swindle an older, desperate woman out of the last remaining vestige of her salad days without rousing other influential Chicagoans into defending the dead man’s memory — which would prove catastrophic for Vera’s defense.

Speaking of Vera’s story, sifting through Vera’s interviews and testimony, the bare bones of her version of events goes like this: After Paul F. Volland closed his office doors, she reiterated her demand for either $5,000 or the Trumbull miniature.

Volland’s response: “I’m tired of looking at you and of listening to you. I haven’t got anymore time to waste. Now, will you get out?”

Unaccustomed to such rudeness but unwilling to leave without at least one of her requests being met, Vera stood her ground. Whereupon, according to Vera, “…{Paul F. Volland} leaped at me. I felt his fingers touching at my throat. He pushed me towards the door. I could stand it no longer. I opened my purse, grasped the pistol and pointed it at him. He leaped at me again and I fired. He dropped in a heap at my feet, gasping: ‘I am shot, I am shot.’ That is all I remember.”

With the potential jury pool now prepped to think Volland attacked first and his death a mere accident, it’s time to cue the next essential element of an acquittal…

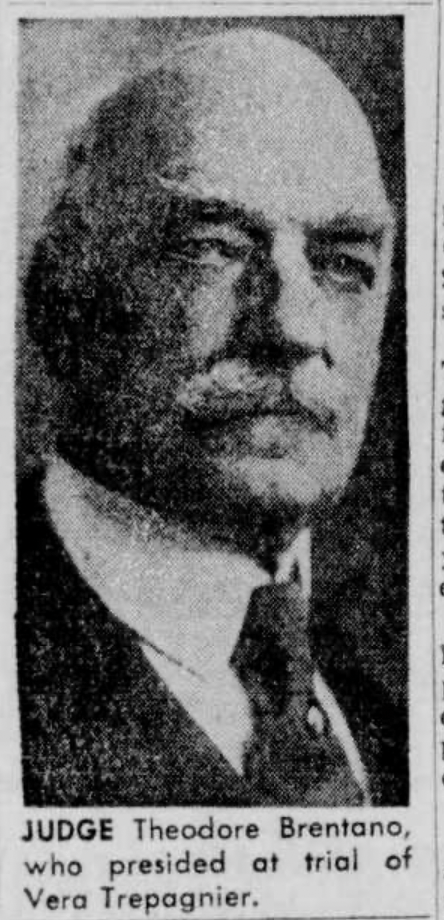

Some of the other players in Vera’s trial.

Step Two: Razzle-dazzle them, or in other words, create a spectacle evocative enough to bamboozle the 12 men of the jury into finding reasonable doubt, whether it’s there or not. This was usually accomplished through effusive weeping, fainting bouts, and statements of abject regret, remorse, and sorrow by the accused in court.

However, these over-the-top demonstrations of contrition didn’t really suit Vera’s case. Seems prior to sinking their teeth into Vera’s tales of woe, the papers reported on her absolutely serene demeanor at the crime scene. According to their words, Vera showed no signs of distress over what she’d done — no shaking hands or voice, no apologies, no tears. In point of fact (and I’m not sure how accurate this is), the papers made it sound as if Vera stepped over Volland as he lay dying on the floor in order to peer out his office windows while waiting for the police.

With standard razzmatazz measures rendered useless, Vera’s lawyers turned to plan B — during her six straight hours on the stand (the only person her defense team called to testify), Vera dramatically reenacted her and Volland’s struggle over the gun. The exhibition highlighted the physical disparity between 44-year-old Paul F. Volland and 60-year-old Vera while attempting to refute the prosecution’s expert witness, who declared it impossible for Vera’s revolver to accidentally discharge in the way Vera claimed. “My {Vera’s} finger was on the trigger. His hand closed over mine, pressed my finger and exploded the weapon. He really shot himself.”

The theatrics didn’t end there.

Endeavoring to bolster Vera’s claim: That Volland attacked first and without provocation thus rendering Vera’s actions understandable. In his opening remarks, Leo Lebosky (one of Vera’s lawyers) attacked Volland’s reputation. Calling Volland a “woman-hater” and “woman-beater” — then claimed Volland’s second ex-wife sought a divorce on the grounds of cruelty. These remarks instantly provoked Assistant State’s Attorney Dwight to raise strenuous objections and Judge Brentano to remind Lebosky that claims along these lines would not be admitted into evidence. This led Lebosky to confidently counter, “…it would be.” (They weren’t, btw.)

In July 1919, with the formula now complete: Crime, sob story, razzle-dazzle, and blaming the victim for their own death (i.e., the killing was accidental), a Cook County jury withdrew from the courtroom to deliberate on Vera’s fate.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.