Now, you’d think arsenic poisoning wouldn’t really square with Chicago’s Murderess Acquittal Formula. Not only because the administration of poison is (predominantly) a covert and (on the whole) premeditated act but on account of the sheer absurdity of translating the foundation of this Formula from “they both reached for the gun” — to — “they both reached for the box of Rough on Rats.”

And yet, a handful of women still turned to this ancient element.

The most notorious of the lot, who spent their fair share of time in Cook County’s Murderess Row, were the serial poisoners Tillie Klimek and Louise Vermilya. However, there is a third, lesser-known member of these ‘Sisters in Bane’ — Louise Lindloff. Who’s life and crimes and subsequent trial had it all — spiritualists, allegations of witness tampering, startling admissions, and a literal crystal ball. So, of course, that’s whose misdeeds we will explore next!

Now that we’ve mastered that portion of the name game let’s examine Louisa Lindloff’s life and multifarious crimes.

Originally, Louisa was born Louise Darkone in Colmar, Germany, on February 4, 1871. Seventeen years later, in March 1888, Louisa married Julius Graunke, who was about two years her senior. Approximately two years later, in April 1890, Louisa and Julius welcomed their first child, a girl they named Frieda, into the world.

Here’s The Deal: In researching the piece, I discovered that while Louise was her legal name, she also went by Lizzie and Louisa. Since Louisa is the name inscribed on her headstone, I will use it from here on out since it seems (if I’m inferring correctly) to be the name she preferred.

Following this joyous event, sometime between 1889 and 1891, Julius crossed the Atlantic Ocean, settled in Milwaukee (Wisconsin), and found work as a driver for the Fitzner & Thompson Commission House before sending for his wife and baby daughter. In short order, the couple expanded their family with a second daughter, Alma, born on December 18, 1891. Finally, Julius and Louisa completed their familial unit with son Arthur Alfred Otto, born on May 19, 1897.

Sadly, misfortune in the form of an undefined, debilitating illness struck Julius around late April or early May of 1905. During his three-month downward spiral, a neighbor, Mrs. Martha Greiner, heard Julius complain: “Louisa, there was something in my last medicine.” Louisa also confided in Martha: “Julius will only live a few days and when he is dead I’ll get $2,600. I’m going to open a saloon and buy a horse and buggy and have a good time.” This prediction came about, just as Louisa foretold, on August 12, 1905.

The death certificate put the cause of death down as sunstroke, and Louisa promptly collected on Julius’s hefty insurance policy.

Surprisingly, Louisa’s prophecy and tawdry comments failed to ring the necessary number of alarm bells within Martha to prompt a visit to the authorities, especially when combined with the sudden death of the Graunke family dog and the baffling death of a flock of chickens on an adjoining property around this period.

Perhaps Martha didn’t want to believe someone she knew was a killer? (Which, in fairness, would slow me down as well. Despite this blog and the sheer quantity of mysteries I’ve read.) Or, more likely, Martha bought (to some degree) into Louisa’s claim of being blessed with second sight since the age of eight. Which would “explain” how she was granted the foreknowledge of the date of her husband’s death. Either way, Martha and the other neighbors remained silent about what they’d seen and heard in the Graunke household.

Even when the thirty-four-year-old mother of three followed up on her promise of ‘having a good time’ and started kicking up her heels with her boarder Charles Lipchow. Who’d not only lived with the Graunke’s for a period before Julius’s death but whose recently deceased mother (or Auntie, I’ve read conflicting newspaper reports) bequeathed him a legacy somewhere between $5,000 and $15,000 (again, there are conflicting amounts). Who, in turn, lavished the bulk of his inheritance upon Louisa.

But, alas, all good things must come to an end.

On August 17, 1906, nearly a year to the day after Julius passed away, Louisa lost her good time Charlie. However, in a stroke of good fortune, before his death, Charles assigned Louisa as the beneficiary of his $550 life insurance policy provided by a cigar maker’s union (of which $116 went towards his funeral in Lincoln Memorial Cemetery).

Whereupon Louisa assuaged her grief by becoming a bride (again) and married William Lindloff on November 7, 1906.

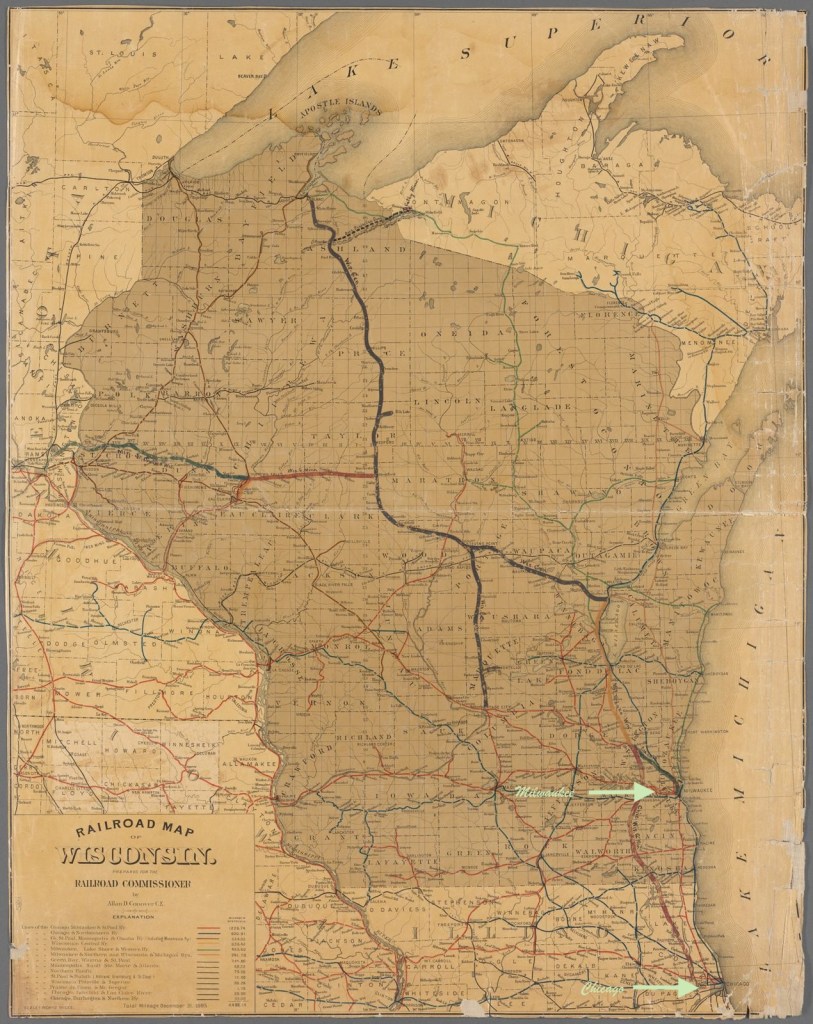

An 1885 railroad map with Milwaukee & Chicago highlighted.

From the Office of Full Disclosure: It’s unclear, exactly when Louisa and her kids moved to 2044 Ogden Avenue in Chicago, Illinois. One account places the move just after Julius’s death in 1905. This would make sense if Louisa was trying to avoid the side-eye and whispers of her neighbors. And Charles’s hefty inheritance would’ve made the move from Milwaukee to Chicago, with three kids in tow, a great deal easier. What muddles the timing of Louisa’s out-of-state move is that Charles died in Wisconsin, not Chicago. So either Louisa moved after Charles’s death, Charles returned to Milwaukee with a belly full of poison and succumbed there or she poisoned him on a return visit?

Compounding my confusion is the fact that Louisa’s second husband worked for the McCormick Harvester Company, which was founded and operated out of Chicago. However, in 1902, McCormick merged with several similar manufacturers to form the International Harvester Company, which operated out of both Illinois and Wisconsin (amongst other states). So did the two meet, court, and marry in Milwaukee, Chicago, or some combination thereof? I’ve not found a copy of their marriage certificate, so I’m unsure.

Then there’s William’s brother, John Otto Lindloff, who resided with the newlyweds. One report I read stated that John Otto’s new sister-in-law absolutely detested the sight of him. Not only because he was courting her eldest daughter Frieda, but on account of the fact he became suspicious of Louisa after drinks and food she’d prepared made him ill immediately afterward. Then, on October 12, 1907, at the age of 24, John Otto died after suffering, for a short period, from dizziness, vomiting, stomach cramps, and other violent symptoms. According to his death certificate he died of apoplexy in Milwaukee, where he was subsequently buried.

Hence why, I lean towards Louisa still living in Milwaukee, at least until 1907. It’s far simpler to slip a little something into someone’s food if you live in the same city, street, and home than Louisa traveling the hundred or so miles up the coast of Lake Michigan from Chicago to Milwaukee in order to perform the deadly deed.

That being said, the distance would provide Louisa with a nice buffer after collecting John Otto’s $2,000 life insurance policy.

Frieda Graunke

In any case, what I do know for certain is that Louisa, William, and the kids were in Chicago by June 11, 1908. As that’s the day Louisa’s eldest daughter, Frieda, unexpectedly passed away at the age of eighteen from typhoid fever and was later laid to rest in Oak Ridge (aka Glen Oak) Cemetery in Cook County, Illinois. It will surprise no one that the young laundress named her mother as the sole beneficiary of a Prudential life insurance policy in the amount of $1,350 before her death.

The reason why I find these timeline and geography questions so frustratingly fascinating is that I’ve no clue if Louisa possessed enough cunning to purposely tango to and fro over state lines in order to obscure her string of murders and subsequent insurance fraud or if it was just coincidence. Nor is it clear if Louisa used nicknames and shiny new surname to further distance herself from her earlier crimes. Either way, by happenstance or design, it worked. Despite four deaths in four years, all of which benefitted Louisa financially, no one questioned her run of bad luck.

Yet.

My 52 Weeks of Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.