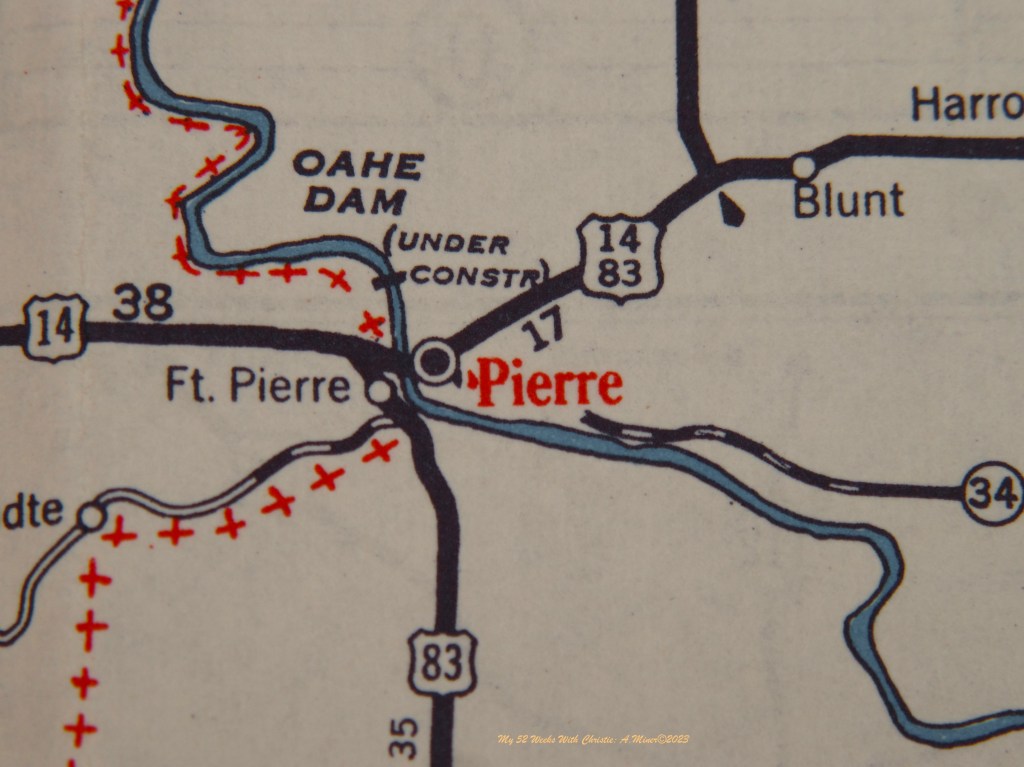

In our last case of Caustic Candy, we will travel roughly three-hundred-and-thirty-seven miles north and slightly west from Hastings, Nebraska, to Pierre, South Dakota, to meet a love-struck woman who nearly managed to send another to prison for a murder she didn’t commit.

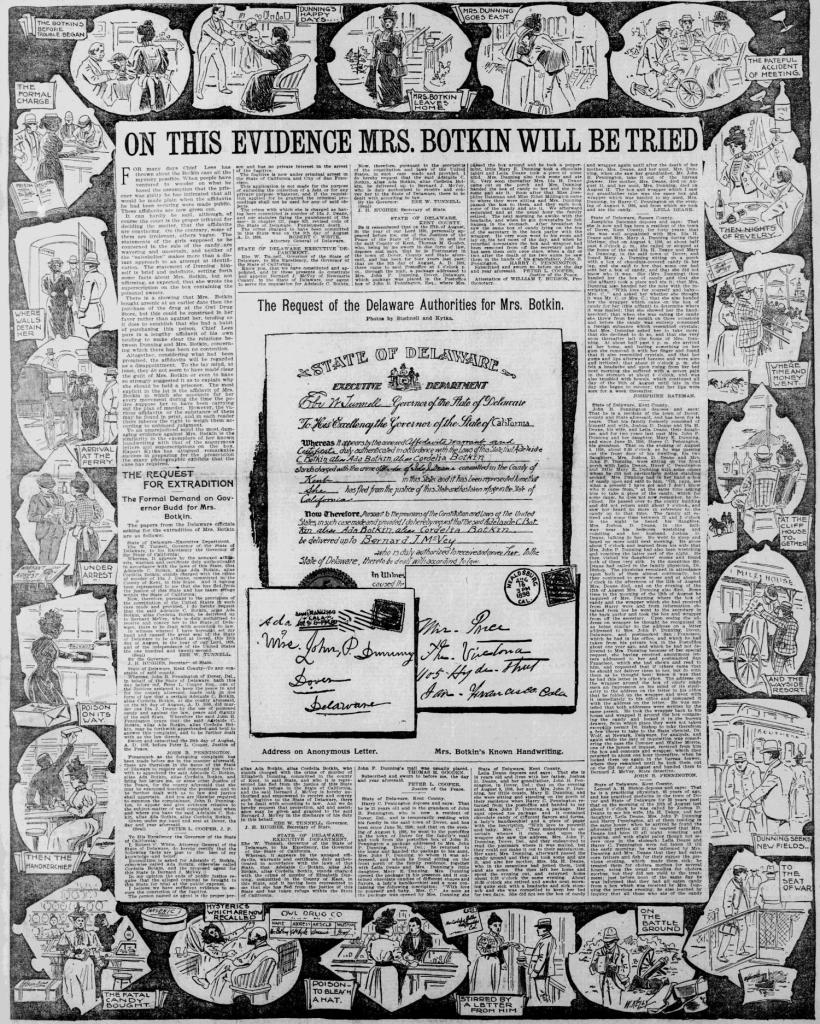

In the years leading up to February 27, 1904 — Cordelia Botkin and her infamous cross-country murders continued to make headlines. (Due in no small part to the upcoming retrial Botkin managed to secure for herself — which would ultimately fail.) Despite the police catching and the prosecutors convicting Cordelia Botkin, her evil exploits still inspired/tempted people across the country into trying to rid themselves of an unwanted lover, rival, enemy, or annoying neighbor by sending said person a box of poisoned laced sweets through the mail.

Enter Rena Nelson.

An unattached woman in her late twenties, Rena lived six miles north of Pierre, South Dakota, on a farm with her parents working as a nurse around the city. (Though, as she had no formal training, I think it’s more likely Rena acted as a nurse’s aide.) In any case, on Saturday, February 27, Rena and her father went into Pierre. One of the must-visit spots, whenever one visited town, was (of course) the post office. On this day, a parcel and a letter waited for Rena. Carefully slitting open the parcel’s wrappings, she discovered someone had sent her a box of chocolates. Popping one in her mouth, Rena stood at a counter chewing whilst reading a letter from her Aunt. By Sunday night, Rena was beginning to feel a little iffy, though still well enough to pen a return letter to her relation in Boone, Iowa. On Monday, Rena’s family sent for the doctor.

Who in turn sent for Sheriff Laughlin.

Whilst slowly succumbing to a hitherto unknown poison her doctor suspected was delivered via bonbon, Sheriff Laughlin listened to Rena point the finger at her own murderer. Taking Rena’s hunch and the suspect box of confectionary with him, the Sheriff left the Nelson household. His first stop was the chemists, where he handed off the sweets for testing. His second was the telegraph office, where he wired his counterpart in Boone, Iowa, asking them to arrest his prime suspect.

By this point, it was Tuesday, March 1, 1904, and the local newspapers got wind of a possible Botkin copycat within their midsts. By the following day, regional papers had picked up the story, and by the next, the national press.

On March 4, the State Chemist, Professor Whitehead, confirmed the local physician’s worst fears: Rena had ingested corrosive sublimate. Otherwise known as mercury chloride, this compound was used in developing photographs, preserving specimens collected by anthropologists & biologists, to treat syphilis, and as a disinfectant. In acute poisoning cases, like Rena’s, the chemical’s corrosive properties wreak havoc on internal organs. Causing ulcers in the mouth, throat, stomach, and intestines. Leading to a burning sensation in the mouth/throat, stomach pain, lethargy, vomiting blood, corrosive bronchitis, and kidney failure. Even today, doctors face an uphill battle in mercury chloride poisoning. Back in 1904, the only option available were iodine salts.

Unfortunately, Rena’s organ damage proved too extensive for any hope of recovery.

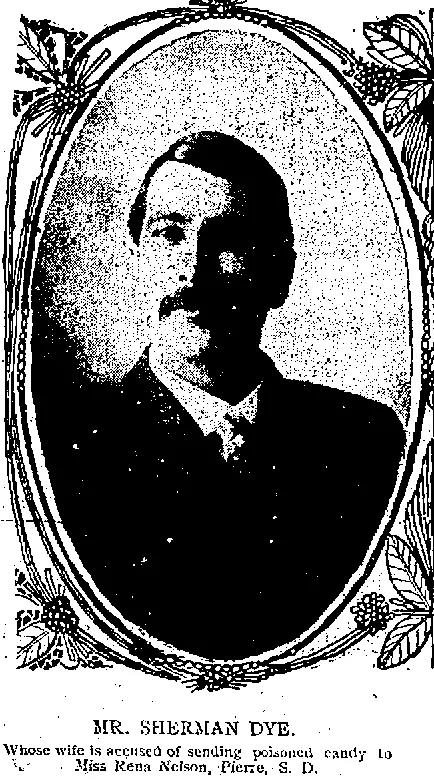

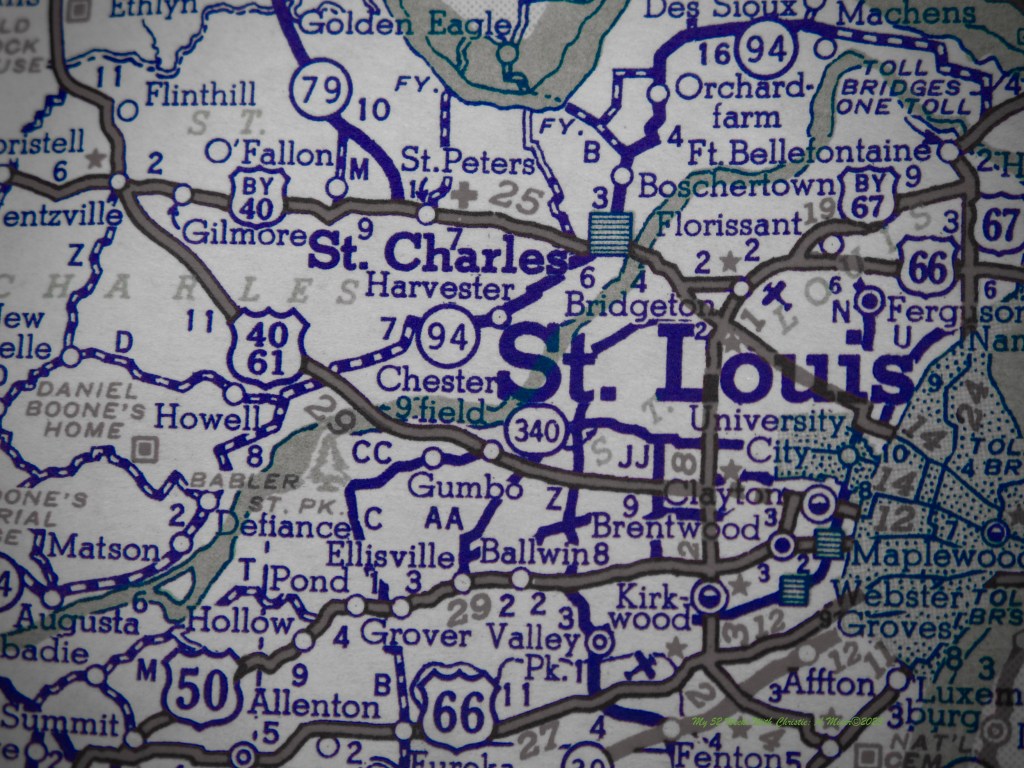

But who did Rena accuse of killing her, and why? This was the question the newspapers, public, and residents of Pierre clamored after Sheriff Laughlin to reveal. For that answer, we must travel back three years to Boone, Iowa. Where for a season, Rena worked at the Boone Telephone Exchange as an operator while living with her Aunt. During this time, Rena met Mr. Sherman Dye, who worked for the Northwestern Railroad as a clerk in one of their roundhouses.

The two soon started dating.

When Rena returned to Pierre, the pair continued their romance via pen & paper and carried on in this fashion for the next two-and-a-half years….Until November 1903, when Mrs. Belle Dye, Sherman’s wife and mother of his child, accidentally discovered Rena’s letters and photos stashed in the family’s chicken coop.

Mr. & Mrs. Dye separated on Christmas 1903.

Now, it’s unclear when Sherman told Rena he was married. However, thanks to the letter Rena penned to her Aunt on that Sunday when she started suffering from the effects of the corrosive sublimate, we do know that Sherman initially ‘misrepresented his marital status’. Telling Rena he’d obtained a divorce. However, when Sherman revealed he was, in fact, still married — for whatever reason — Rena chose to continue the relationship rather than giving him the old heave-ho.

Rena even went so far as to write Belle several letters asking her to grant Sherman a divorce as he wanted to marry her.

Finally, on January 23, 1904, Belle wrote back, asking Rena to leave them both alone — pointing out that she was ‘interfering with a husband and wife.’ And therein lies the crux of Rena’s deathbed accusation. She claimed Belle was jealous because Sherman transferred his affections from his wife onto herself. Rena also told the Sheriff she recognized the handwriting on the parcel’s wrapping as that of Mrs. Belle Dye’s — but only after ingesting the poison-laced chocolates.

On March 6, 1904, with a South Dakota issued arrest warrant in hand, Sheriff Laughlin arrested Belle Dye — in Boone, Iowa.

Unfortunately, for Sheriff Laughlin, returning to South Dakota with Belle in tow wasn’t as easy as simply catching a train. Facing the same conundrum his counterparts in California and Delaware found themselves in a few years prior with Cordelia Botkin — Sheriff Laughlin needed to navigate Iowa law, which had never faced a case where the (impending) murder took place in a separate state from where the instrument of destruction was mailed from. The first blow to the Sheriff’s extradition of Belle came when the Iowa Supreme Court quashed the North Dakota arrest warrant — which labeled Belle as a fugitive from justice. However, since Belle never entered South Dakota, it followed that she’d not fled back to Iowa afterwards.

So, by definition of the law, Belle wasn’t a fugitive.

Not willing to let this woman get away with murder, Sheriff met with Iowa’s Governor Cummings on March 7, hoping he’d intervene. While he did, on advice from State Attorney General Mullan, Governor Cummings made a different call than his Californian counterpart. Not only did he free Belle on March 9 with a writ of habits corpus, he also let Sheriff Laughlin know that Belle could neither be extradited to South Dakota nor would she meet a murder charges in Iowa.

Belle needed to be tried in South Dakota, where the deed took place, or not at all.

Undoubtedly, seeing which way the wind was blowing before Governor Cumming made his announcement, Sheriff Laughlin made one last Hail Mary play to get Belle Dye back to South Dakota to face justice — he applied to the US Postal Inspection Service. As one of the only investigative federal bodies at the time (the precursor to the FBI wouldn’t be founded until four years later), the Sheriff hoped they’d charge Belle with misuse of the mail. (As sending poison thru the post was, and is still, illegal.) If the Special Agents found enough evidence to charge her, then Federal Marshals could cross state lines, arrest Belle without a warrant, and bring her back to South Dakota.

Whilst all this legal wrangling went on, Rena Nelson died on March 8, 1904.

Noticeably absent from the side of Rena’s deathbed was Sherman Dye. Rather than comforting his dying lover, he chose to support his wife during her detention. Not only defending Belle in the press, Sherman also paid multiple visits to Belle in jail with their daughter Dolly.

On March 10, the same day Postal Service Special Agents arrived in Pierre — the Coroner’s Inquest into Rena’s death was held. The verdict from the jury was a foregone conclusion: “Miss Nelson came to her death through eating some tablets or chocolate candies contained in a box received through the United States Mail at Pierre, South Dakota and postmarked Boone, Iowa and contained corrosive sublimate in sufficient quantities to cause death.”

However, the most significant feature of the inquest, which would throw the whole case on its ear, occurred as the spectators congregated outside the courthouse discussing the case….

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.