My inspiration….

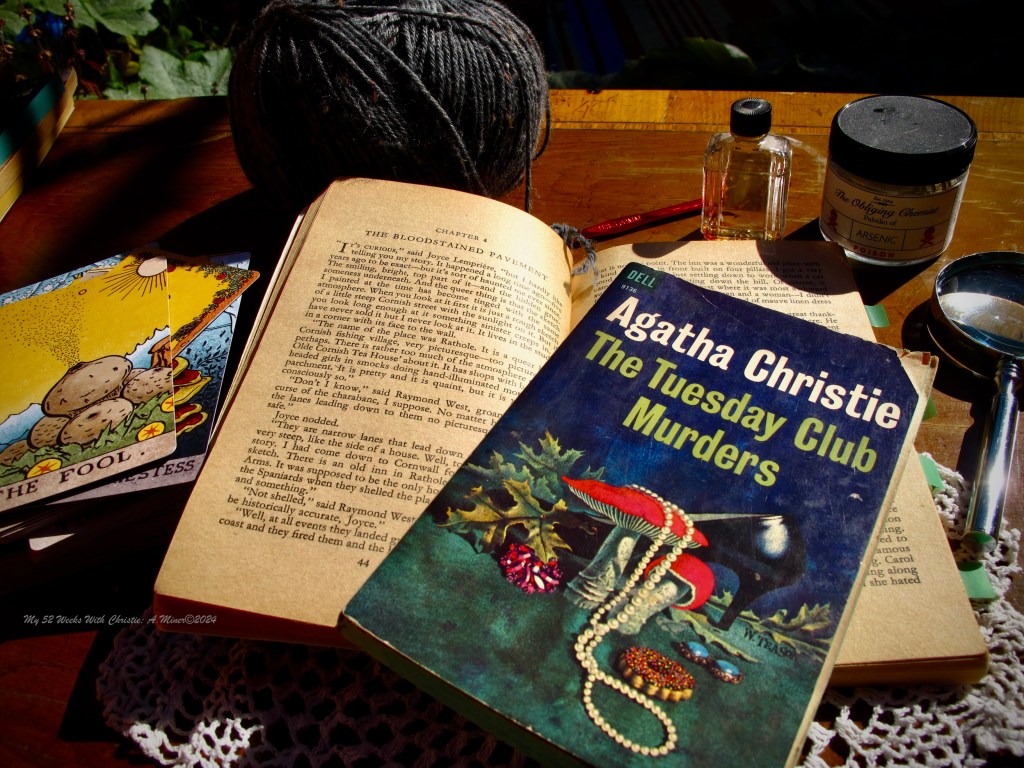

Recently, on a whim, I reread the Miss Marple short story The Bloodstained Pavement. After finishing the story (for the umpteenth time), an idle thought crossed my mind: I wonder if an artist has ever solved a crime whilst painting a painting? Curiosity sparked, I plugged in some keywords into an old newspaper archive.

It came back with:

Diverted by this curious headline (mere minutes after my original query flew through my head), I jotted down the brief list of names printed below the photo collage. Deciding I could spare a few seconds to suss out the meaning of this singular bit of news — I, in a fair imitation of The Fool, blithely stepped off an unobserved precipice.

Fast forward several months.

Surfacing from a mares’ nest of mind-boggling murders, wafer-thin defenses, and musical numbers — I’d grasped a slender thread (loosely) linking The Bloodstained Pavement and the aforementioned fantastic headline to a crap ton of crime in Chicago spanning betwixt 1907 to 1919.

And it all starts with an artist named John Trumbull.

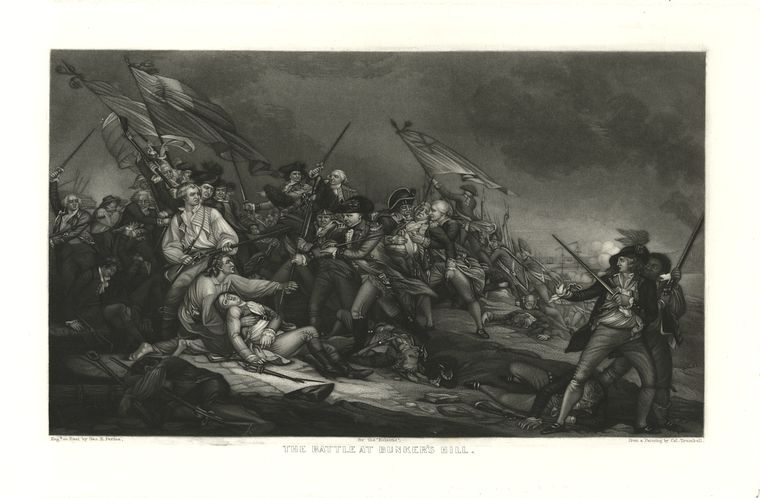

Never heard of him before? Well, ten to one, you’ve probably seen his work: in history books, if you’ve ever been to the rotunda in the U.S. Capitol building (in Washington D.C.), scanned the back of a two-dollar bill, or gazed upon Alexander Hamilton’s portrait on a ten spot. How did Trumbull find himself commissioned with such momentous projects? Well, between being the son of Connecticut’s Governor, graduating from Harvard, and serving under George Washington & Horatio Gates during the American Revolution — Trumbull met a plethora of the fledgling country’s early leaders.

The scenes were all painted by Trumbull and the Portrait is of Trumbull himself.

However, before Trumbull became known for his hyper-detailed life-sized scenes, earned a commission from Congress, or painted the portraits of several founding fathers — he sailed for London in 1780. Unsurprisingly, whilst in the capital of the UK, Trumbull met up with Benjamin Franklin. (Seriously, Trumbull’s life is a who’s who of historical figures.) Franklin, in turn, introduced the aspiring artist to Benjamin West — whose subject matter meshed well with Trumbull’s artistic aspirations. Under West’s tutelage, Trumbull began practicing painting techniques by filling small canvasses with images of the war he’d fought in and miniature portraits.

Apparently, Trumbull enjoyed the latter exercise so much that he’d go on to paint over 250 of these mini-pics over the next 63-ish years.

Amongst the bevy of minis Trumbull created was a portrait of George Washington (one of his favorite subjects). Painted in predominantly blues and golds on an oval-shaped piece of ivory, it measured 2.25 by 1.75 inches. According to legend, after completing the Lilliputian sized portrait, Trumbull presented it to a Virginian bride as a wedding gift. After this, this unnamed bride moved both herself and the pocket-sized portrait to Kentucky. Next, the fun-sized painting relocated with one of her kids to Tennessee, her grandkids decamped with it in tow to Arkansas, and finally, it wound up in Louisiana, where it was gifted to Vera Trepagnier.

Elizabeth Vera McCullough or Vera (as she seemed to prefer), was born into a wealthy family in Belfast, Ireland, around 1860. Round about the age of seventeen, she and her family immigrated to the U.S. and settled in Louisiana. Sometime over the next seven years, Vera caught the eye of her future husband and sugar planter — Francois Edmund Trepagnier. The two married around 1886, when Vera was 24 and Francois was 52 (give or take). They had a son by the following year.

(Upon marrying Francois, Vera also became the stepmother to three kids from Francois’s first marriage — the eldest of whom was only two years younger than herself….which sounds….awkward.)

Fast-forward four years to when the Trepagnier sugar plantation flooded and ruined their entire crop. In the wake of the devastation and unable to recover, Francois and Vera were forced to economize: first, they let go of all their servants, then sold all their furniture, and finally, the plantation itself. Sadly, despite trying to find a fresh start in Florida, the pressure of unexpectedly tumbling downwards through a significant number of tax brackets proved too much for Francois. Who, whether by illness or suicide (it’s unclear), passed away around 1891.

Despite losing her husband, estate, and way of life, Vera retained possession of the diminutive Trumbull portrait.

In 1916, during the WWI war effort, about twenty-five years after these life-altering events, found Vera working for the Treasury Department in Washington D.C. Now a grandmother who wanted to help her grandson get a good education, Vera finally decided to investigate the legend around her pocket-sized portrait. Placing the ivory miniature beneath the lens of a microscope for a better look at the artist’s signature, Vera discovered the painting’s lore true. Even better, thanks to the private tutors who’d educated her in her youth, Vera not only knew who Trumbull was, she understood how valuable a rendering of George Washington by his hand could be.

With this knowledge, Vera traveled to Philadelphia, hoping to make money off the tiny thing while (hopefully) retaining possession of it.

(Cue dramatic music.)

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.