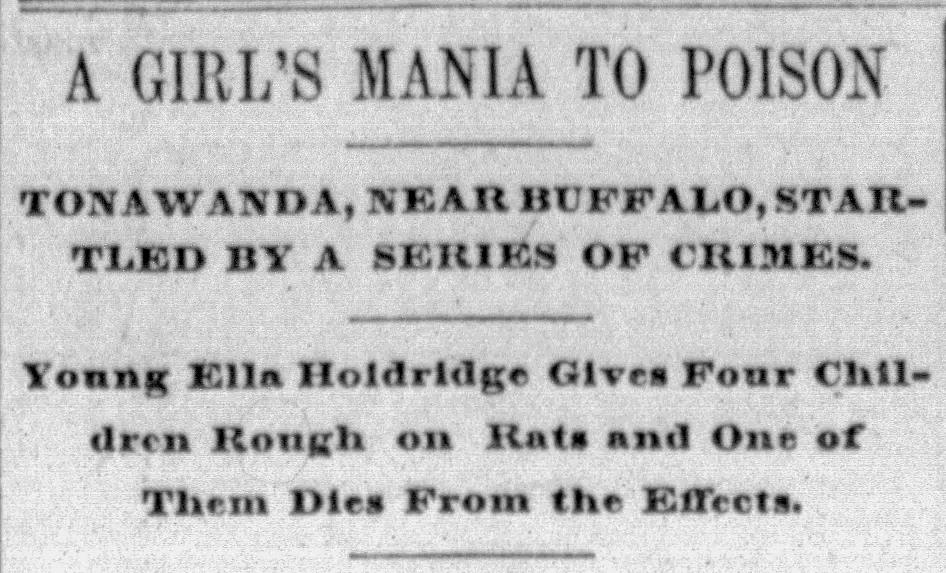

Flush with success and brimming with confidence over her first induced funeral, Ella Holdridge waited (about) five days before feeding her obsession with death, funerals, and wakes.

Only this time, Ella made a mistake.

Whilst plenty of people noticed the two girls playing together on the day Leona fell ill, no one for a moment suspected Ella played a role in the toddler’s lingering death. Mainly because of the two-year-old’s inability to utter anything sensible after ingesting the water Ella polluted with Rough on Rats.

However, this time, Ella targeted a pair of sisters — Susie & Jennie Eggleston.

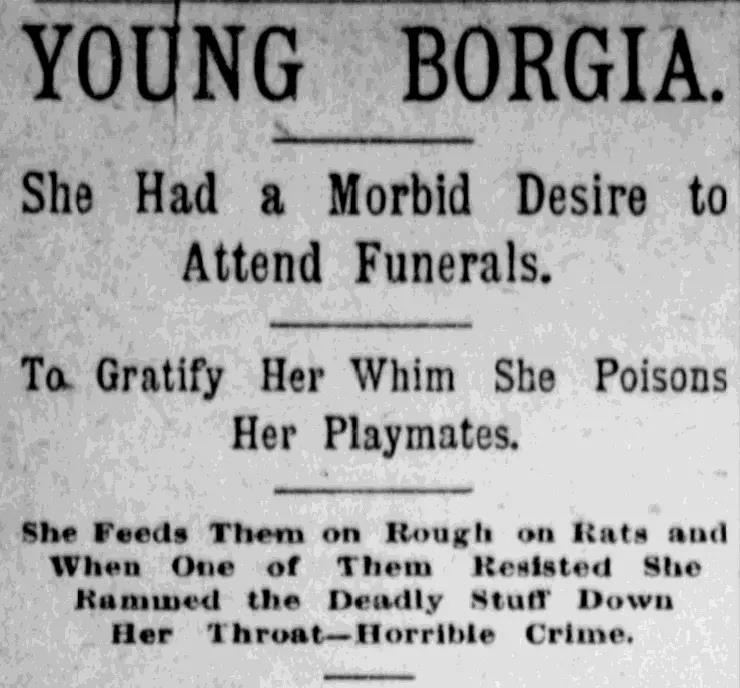

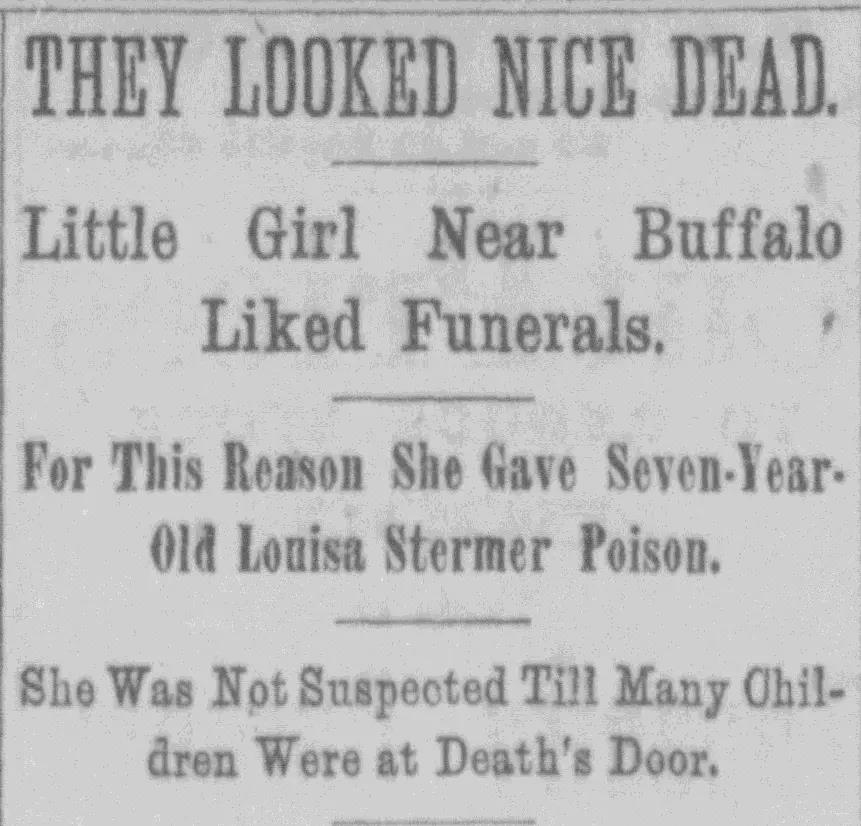

Due to the sensationalization of this case, there’s some ambiguity on what exactly happened next. (Newspapers of this era absolutely loved to hype up crimes like this — often at the expense of the facts.) However, these things seem certain: In and around July 16, 1892, Mrs. Eggelston decided to go shopping in Buffalo, NY (about twelve miles from their neighborhood in Tonawanda) — leaving her daughters at home. Now, one way or another, either knowing beforehand via the neighborhood grapevine or sussing out the intelligence from the pair as they played on their front porch — Ella realized the lack of adult supervision afforded her an opportunity to generate a double funeral.

Using her status as an older kid (as she was fourteen to their ten and five) and the promise of making them “something nice,” Ella managed to herd the two inside their house. After (possibly) locking the doors after they went inside, Ella made a pot of cocoa with a generous measure of her secret ingredient, Rough on Rats, thrown in. When one of the sisters complained about the cocoa’s taste and refused to drink anymore, Ella compelled the girl to drink it: Through either verbal coercion, pushing her onto a sofa and pouring it down her throat, or throwing her onto the floor and forcing the liquid between her lips. After ensuring Susie and Jennie finished their mugs of cocoa, Ella told them not to tell anyone about what happened and left.

Later that evening, both girls became extraordinarily ill and their parents sent for Dr. Edmunds.

As both Susie and Jennie had been the picture of health prior to their mother’s trip into Buffalo and they’d pretty much identical symptoms which started nearly simultaneously — Dr. Edmunds suspected they’d gotten into something poisonous. Can you imagine his surprise upon learning about Ella’s strange-tasting hot chocolate and even stranger behavior? Then word reached him about another kid a few doors down who was desperately sick — with the same symptoms as the Eggelston sisters.

Seems sometime during the day, Ella also administered some Rough on Rats to five-year-old Ervin Garlock.

Whilst doctors worked diligently to save the lives of the three kids — news of Ella’s possibly poisonous food and drink spread like wildfire around the neighborhood of Kohler and Morgan Street. Leading every parent hither, thither, and yon to interrogate their children as to whether they’d eaten anything given to them by Ella.

After Susie, Jennie, and Ervin’s lives were back on solid footing, Dr. Edmunds and Dr. Harris compared notes….and discovered Leona’s symptoms mirrored those of the other poisoned children. Unsurprisingly, the duo of doctors took their suspicions to Justice of the Peace Rogers and Coroner Hardleben — who called Ella in for questioning posts haste.

At first, the fourteen-year-old denied everything.

However, when one of the officials bluffed and told Ella someone had seen her making the cocoa, and they knew she’d put poison in it — she opened her eyes wide and said….“Dear me, is that so?” And went on to make a full confession. Telling the adults she’d poisoned Susie and Jennie: “…because she wanted to go to a funeral, and thought they would look so nice dead.” When they asked after Leona’s murder: “Yes, she’s dead. Poor L{eona} But she looked awful pretty and her funeral was awful nice.” When Justice of the Peace Richard asked why she used Rough on Rats, Ella replied: “If it killed rats and mice it would kill children.”

(Prompting authorities to exhume poor Leona’s body and send her stomach to Dr. Vandenbergh for analysis.)

On July 16, 1892, Ella was charged with murder.….and this is where things get a bit murky.

I know on July 18, 1892, Franklin Holdridge (Ella’s Dad) committed Ella to the care of Father Baker’s Institution at Limestone Hill. I believe the “institution” the papers referenced was a protectory.

(The above picture was printed in an atlas about thirty-five years prior to Ella’s hasty trip to said Institution.)

Protectories are akin to nonreligious reform or industrial schools. They took in all kinds of kids, from orphans to juvenile delinquents — educated them in religion, morals, and science, then trained them in a trade or for a manufacturing position. Whilst not a prison, Father Baker’s protectory would afford far more supervision and possible rehabilitation for a budding poisoner. (It undoubtedly gave Ella space from her obsession because I can’t imagine the nuns or priests in charge would’ve allowed her to attend funerals or visit the graveyard — given her history.)

In any case, this prompt change of address not only kept the children in Ella’s old neighborhood safe, including her much younger siblings, it might’ve also (possibly) given the jury a reason to find her not guilty.

I say possibly because, unfortunately, I can’t find any direct news pieces on Ella’s trial. Save a blurb written just under eight years after the events of July 1892. It states that despite Ella’s confession and testimony in which she reiterated her belief that Leona and the others would “…look well dead…” a “…jury didn’t see fit to punish her.”

Perhaps Ella pleaded insanity? Or, due to her age, her lawyers argued she didn’t understand the enormity of her actions? Or maybe they didn’t want to send a pretty young girl to jail for the rest of her life. I don’t honestly know. However, I suspect it didn’t hurt that of her four victims — Susie, Jennie, and Ervin managed to live through the ordeal she put them through.

I also reckon Ella remained in Father Baker’s care for a spell after her trial, though this is purely conjecture on my part. (Mostly because I can’t see a way for her to return home to Tonawanda after killing a child, no matter the outcome of a trial. Though again, it is possible.)

(Ella, from later in life. From findagrave.com)

However, I do know that by the time Ella was about 24, she was married to a man named Neil McGilvray with a baby daughter on the way. In 1905, they had another daughter. In 1908, the family moved to Monessen, Pennsylvania, where Ella would remain for the next 37 years until her death in 1945 at the age of 65.

You must be logged in to post a comment.