Chapter 1: The Moving Finger & A Real Life Poison Pen Case

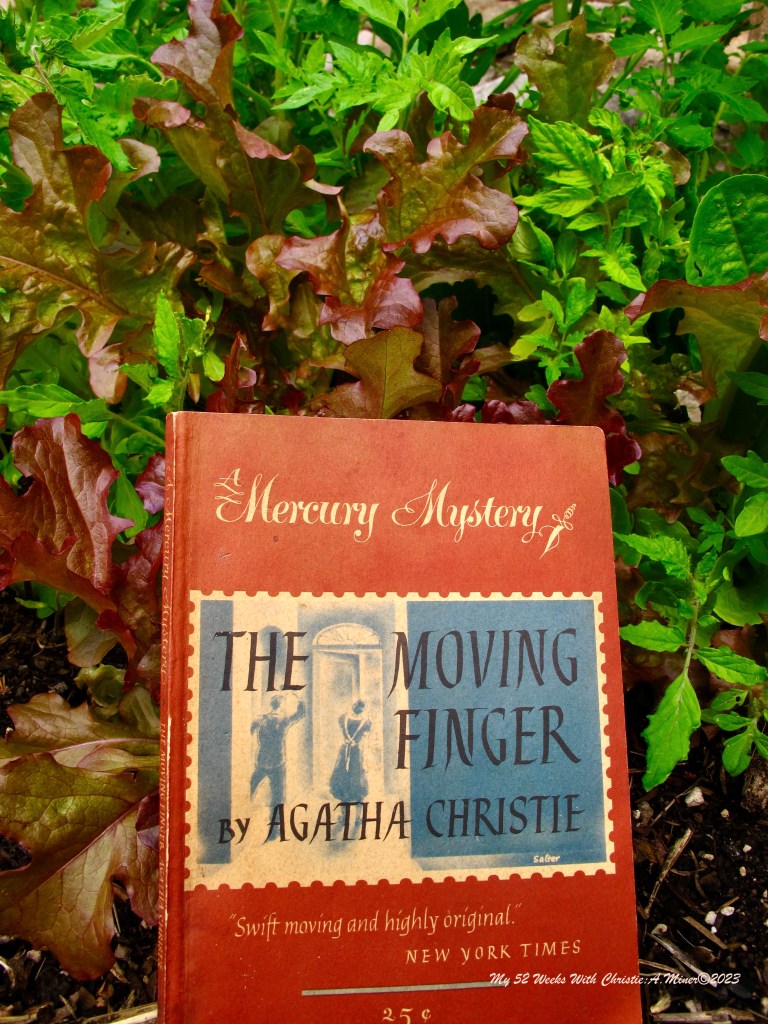

Recently I found myself stuck in a mental fog bank with an overwhelming urge to read something more involved than the instructions on a jug of laundry detergent. So I turned to my bookshelves for help. Knowing from past experiences that new stories are a no-go, I ran my finger along the spines until my eyes and index digit landed on The Moving Finger. At which point my brain sat up and bellowed YAHTZEE! Not a new read, but one I hadn’t cracked the covers of since 2014.

Stoked, I sat down and devoured it whole.

Discovering, much to my surprise, my perspective on this classic mystery shifted since I’d last read it nine years ago. (Amusingly, I’d also forgotten the malefactor’s identity and was fooled all over again by the Grand Dame of Misdirection.) Rather than impatiently waiting for Miss Marple’s entrance from stage left or touching the cherished memory of howling with laughter at Victor Borge’s bit on inflationary language with my grandfather in the basement of his house one summer afternoon — my mind caught on the McGuffin of The Moving Finger: the poison pen letters.

Since the villain in The Moving Finger used these letters to mask his true intent, which didn’t seem to fit with what I knew of the phenomenon, it made me wonder what actually drives a true poison pen writer to pick up their quill, so to speak.* Moreover, I wondered why the police and residents of Lymstock so readily accepted the idea that Mrs. Mona Symmington committed suicide over a single letter. So, on a day when the mental fog receded to the outer banks of my brain, I began looking for answers….and fell down a veritable rabbit hole.

Turns out I should’ve had more faith in one of my all-time favorite authoresses.

An view of Tulle from back in the day!

Twenty years prior to the publication of The Moving Finger, a small city in France found itself a hotbed of this postal based crime. From 1917 to 1922, over one-hundred-and-ten poison pen letters were opened in the small provincial town of Tulle. (Where the epitomes fabric of the same name was originally invented and manufactured.) And by the time authorities finally stemmed the flow of these malicious missives — three people were dead, two were remanded to lunatic asylums, and at least one recipient suffered a nervous breakdown. Not to mention the countless broken marriages, shattered friendships, and ruined careers these slanderous communiques also caused.

And it all started over a boy.

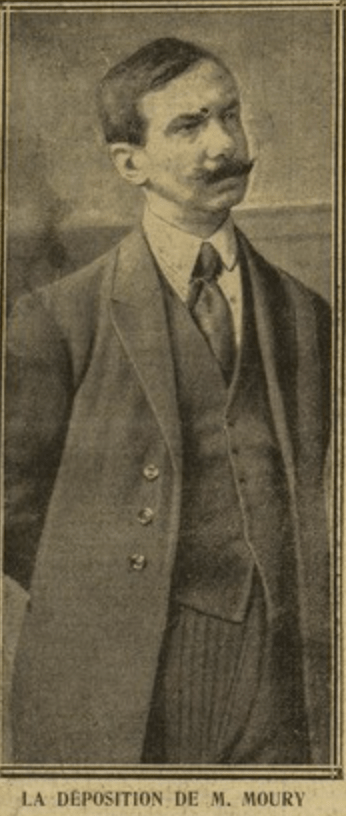

Thanks to the overwhelming number of men called up to fight in WWI and her brother’s professional influence, Angele Laval secured a job within Tulle’s prefecture (police department) as a typist under the supervision of Jean-Baptise Mouray.

Jean-Baptise Mouray

Now it’s unclear how long the two worked together before Mouray became the object of Angele’s obsessive affections and due to conflicting contemporary newspaper reports it’s also unclear if: A) Angele loved Mouray from afar. B) Mouray rebuffed Angele’s romantic overtures due to lack of attraction on his part. C) Mouray and Angele dated for a period before he threw her over. However, we do know by 1917, Angele had hatched a plan to draw Mouray into her web.

By sending him an anonymous note abusing her own character.

Troubled by the unsigned slander aimed at his subordinate, Mouray stewed over the ill-natured intelligence for three days before bringing it to Angele. Who, upon laying eyes on the missive, produced one of her own. Only her’s was “left” on her desk at the prefecture and cast aspersions on Mouray’s character instead (calling him a seducer and such). Fearful the crude letters could harm her reputation and his career they decided to keep the contents a secret and consigned them to crackling flames found within a stove in the prefecture’s accounting office.

Unfortunately, this shared secret did not spark the love affair Angele presumably hoped the notes would ignite. Even worse? In 1918 Mouray hired a new typist for their department, Marie-Antoinette Fioux, whom Mouray soon developed an interested and in 1919 began dating.

Rather than giving up on her dream of romance or in a fit of “If he won’t love me, he can’t love anyone else” or both — Angele Laval turned to her inkwell once again. Churning out several crude letters to Mouray’s sister, denouncing Marie-Antoinette’s character. When that failed to produce the desired result, Angele directed another anonymous note to Mouray — this time taunting him with the knowledge of a child he’d fathered with his mistress.

This did the trick.

Apparently, at some point along the way Marie-Antoinette inadvertently witnesses Mouray leaving his mistress’s home. As he’d taken great care to conceal both said mistress and his illegitimate child from everyone in the prefecture and (more importantly) his mother — Mouray concluded Marie-Antoinette must be the author of these scurrilous notes and broke thing off.

This breakup slowed, but didn’t stop, the flow of the poison pen letters being posted. Cunningly, whilst trying to drive a wedge between her rival and her love, Angele camouflaged the true object of her obsession by mailing malicious missives to a number of people within or closely connected to the prefecture of Tulle (including its head) over the course 1918 & 1919. Not to say these catty pieces of correspondence were harmless, far from it, but they’d remained focused on the prefecture itself. Until 1920, after convincing her beloved of her innocence, Mouray married Marie-Antoinette — and — invited Angele to his wedding reception.

Prompting Angele to well and truly lose her nut.

*(BTW: Using a smokescreen of like crimes to hide a black hat’s true target is a well established mystery trope. One Christie used with great effect seven years prior in The A.B.C. Murders. But I digress.)

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.