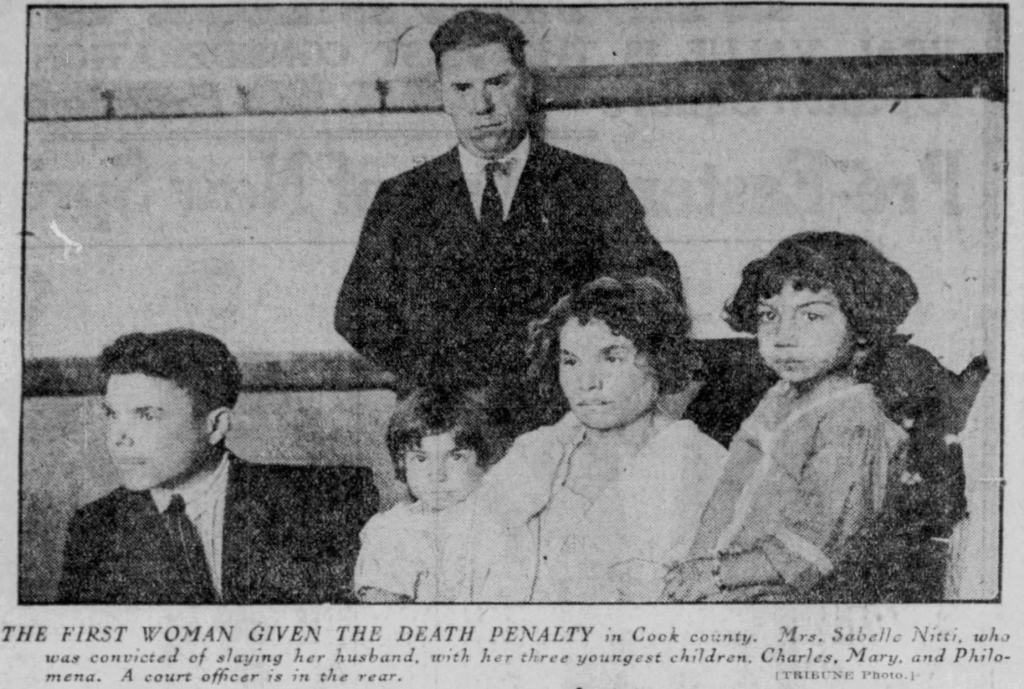

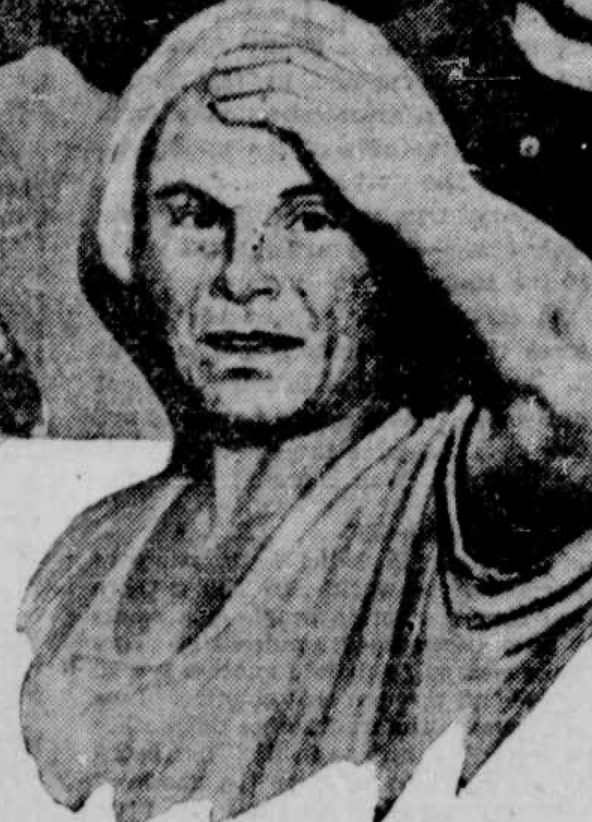

Troubled by Genevieve Forbes’ snide descriptions of Isabella — which, thanks to the syndication of newspaper articles, extended her coverage from coast to coast and inspired other (though not all) reporters to follow her lead — Isabella’s quintet of lawyers crafted a secondary strategy over and above their legal maneuvering. The plan, reminiscent of George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 play Pygmalion (only with far higher stakes than a simple bet), saw the defense team using the months between the stay of execution and the hearing before the Illinois Supreme Court to transform Isabella.

Spearheaded by Helen Cirese (the first Italian American female lawyer admitted to the Illinois State Bar) and supported by Margaret Bonelli (the wife of another of Isabella’s lawyers), they sought to neutralize the press’s unsparing criticism of Isabella. Fully aware her appearance played a role in her conviction, Isabella eagerly agreed. Deferring to the duo’s expertise, Isabella allowed a hairdresser to dye and cut her hair into a modern, flattering style. They visited Murderess Row’s cosmetics cabinet, where Isabella was tutored on the artful application of make-up. Next, Helen bought a new dress, silk stockings, a fur coat, and a hat for Isabella to wear during court appearances.

Well aware that these superficial changes were not enough, Helen, Margaret, and Isabella settled into more exacting lessons. First and foremost, they worked on improving Isabella’s nearly nonexistent English. This not only allowed Isabella to aid in her own defense but also meant she could finally interact with reporters.

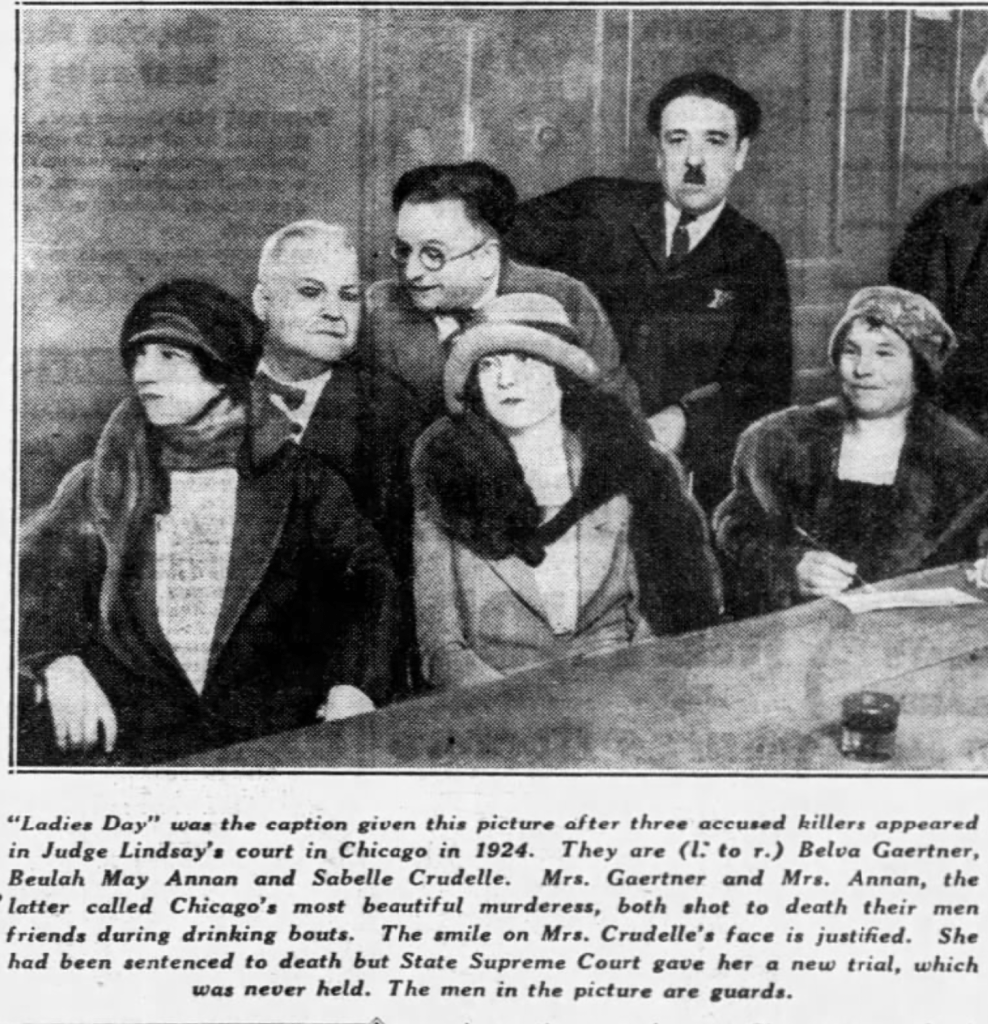

Headlines of a similar nature appeared in all kinds of papers along with photos of Isabela’s “improved” appearance.

Next, Helen tutored Isabella on general American manners and deportment, the lack of which Genevieve Forbes took such a massive issue with (amongst other things). Grunting as a form of communication, while perfectly acceptable when she was growing up, amongst immigrants of similar backgrounds, and family — led to some of the most derogatory descriptions in the press. Hence, Isabella needed to unlearn this practice. Next, Isabella worked at holding back the habit of rocking in place, as this nervous habit also led to disparaging comments. Finally, Helen taught Isabella what was considered “proper” courtroom etiquette — sitting up straight, crossing her ankles, attentively watching the courtroom, and other such (inane) but necessary behaviors.

While no amount of “Americanization” would ever appease Genevieve Forbes and others of her ilk — it did shift the majority of their remarks from strictly dehumanizing to simple snark. Other reporters, less invested in painting Isabella as an “…old, ugly, Italian peasant woman…”, started penning pieces that were (by comparison) more neutral in tone. Moreover, Isabella’s rapidly improving English meant she could interact with reporters, and she did. Isabella spoke of her babies waiting for her at home, of her innocence, and awareness of how her features played a role in her conviction — all of which helped humanize Isabella to the readers of the various rags around the country.

By the time the Illinois Supreme Court returned with its final ruling in November 1924 (I think), Isabella’s transformation was essentially complete….and gave, as intended, the Assistant States Attorney fits. Gone from the defendant’s chair was the “ugly” Italian woman he steamrolled with the press’s help. Instead, he found a smiling “Americanized” Isabella — surrounded by a bevy of highly competent lawyers.

Lawyers who not only successfully persuaded the Illinois Supreme Court to overturn Isabella’s conviction and order a new trial for both Isabella and Peter. They also successfully argued the Court to disallow Isabella’s son Charles’s confession, ruling the body presented as the missing Frank Nitti couldn’t actually be proven as being Frank’s and deemed a whole bunch more circumstantial evidence inadmissible. The death knell of Assistant State’s Attorney Smith’s case came on December 2, 1924 — when it was announced Charles Nitti refused to testify against his mother in a second trial.

A few days later, Smith dropped all charges against Isabella and Peter.

Thanks to Maurine Dallas Watkins’ play and the subsequent musical adaptation, Isabella’s case is now (in)famous. However, after scratching the surface, there’s far more at play in Isabella and Peter’s charge/conviction/successful appeal on first-degree murder charges than just one woman’s appearance….However, thanks to Genevieve Forbes’ unrelenting coverage, Isabella’s features played a far more significant role in her conviction than they should’ve.

Postscript: Frank Nitti’s disappearance and probable murder remain unsolved to this day. One of the background reasons why suspicion initially clung to Isabella was Frank’s brother James and at least one of Isabella’s sons believed Isabella started an affair with Peter before Frank went missing. Furthermore, one of Isabella’s sons contributed money to the prosecution, giving ASA Smith additional incentive to pursue Isabella.

All things being equal, I’ve no clue if Isabella and/or Peter buried Frank Nitti in a shallow grave — but I lean towards not.

However, Isabella believed she knew the author of all: “It was my son, Mike, who was mad because his father wouldn’t give him money to get married on…..Mike would keep still and let me die, so now I’ll tell on him.” Apparently, father and son got into a fistfight over $400 (about $7,250 in today’s money) after Frank refused to lend the hefty sum to his second oldest a few days before his evanescence. Moreover, Mike silenced everyone connected, save his mother (and I’m assuming Peter), by threatening to kill anyone who testified to witnessing said event.

Actions which don’t exactly scream innocence.

Though…If Mike did commit patricide, it could explain why Charles peddled the story of dumping their father’s body in the Des Plaines River with Peter. Mike could’ve, endeavoring to cover all his bases, threatened/bullied/cajoled his younger brother into the confession. Granted, this is pure supposition on my part, but Charles coming forward to accuse his mother bothers me. Assuming he wasn’t a vindictive jerk and Isabella didn’t do it — why would Charles come forward with such a tale?

In any case, in an odd twist of fate, on September 10, 1925 — Isabella was forced to visit the State’s Attorney’s office again. Only this time, she reported Peter Crudelle missing. On September 7, after taking a load of vegetables to market, Peter failed to return home with either their truck or the day’s earnings. It’s unclear precisely what happened to him, however, I read a rumor that Peter returned to Italy and married another woman.

As for Isabella, she married Guiseppe Campobasso on November 2, 1940. Shortly thereafter, the couple became naturalized US citizens and moved to Los Angeles, where they resided (hopefully, happily) until Isabella passed away on December 10, 1957, at the age of 78.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.