Whilst there weren’t any reports of jiggery-pokery in Gertrude’s trial, there are several odd discrepancies when you compare Gertrude’s single unguarded statement to a reporter against her, Robert, Laura, and (her mother) Sarah’s subsequent testimony.

(Gertrude’s remarks to a reporter)

Ignoring Gertrude’s denial of adding Rough on Rats to the coffee pot, the first disparity between this newspaper clipping and courtroom testimony comes when Gertrude explains what prompted her to buy the box of Rough on Rats. Above, she claims her father sent her to the drugstore to buy the rat poison. In the courtroom, Gertrude switched her story, stating the purchase was made because the night before the murder, her mother commented on how “rats {were} going to take the place.” A statement Sarah, her mother, corroborated under oath.

So, which is true?

Did her defense team decide to put forth the trial version, as it had someone who could truthfully attest to its accuracy and doesn’t wholly negate Gertrude’s initial statement to the paper? Or was a convenient circumstance, recalled later, used to mask Gertrude’s childish revenge plan? And if you owned two reasonable explanations for purchasing the poison, why keep mum during Dr. Kaltenbach and her Aunt’s initial inquisitions? Unless you hadn’t anything other than the ugly truth to tell….

However, the most telling inconsistencies betwixt Gertrude’s unscripted answers and later testimony occur over the family’s upright organ and Gertrude’s state of mind.

1) Robert: “…no trouble existed between himself…and Gertrude or between his wife and Gertrude….we never had any trouble about the family organ, and had no intention of removing it, from the home of my parents…”

—— I suppose it’s just possible that a newly married older brother could’ve been entirely oblivious to his younger sister’s upset…..

2) Laura: “She seemed envious at times, but this lasted only a short time, and there was no positive enmity between them….Her husband had stated to her that he did not intend to take the organ with them….”

—— ….Laura, however, was not oblivious to Gertrude’s jealousy, which conflicts with Robert’s rosy view of their relationship with Gertrude. I also find it difficult to believe Laura didn’t bring up Gertrude’s envy issues with her husband. Because, in theory, he’d have a better idea of how to handle a green-eyed little sister.

Moreover, I think this bit, “Her husband had stated…he did not intend to take the organ…” is a potential lie by omission as Laura’s not revealing her intentions on the organ but simply regurgitating her husband’s. Yes, I know at that point in time, a wife was expected to abide by her husband’s decisions…..But this calls to mind an axiom from My Big Fat Greek Wedding — “The man is the head {of the family}, but the woman is the neck. And she can turn the head any way she wants.”

3) Sarah: “…Gertie always treated her father as well as any child could. There had never been any trouble between members of the family or children only what would naturally arise.”

—— A belief Sarah could’ve held right up until she poured the poison-laced coffee that night.

On the whole, the testimony of Gertrude’s kin successfully contradicted, or at least partially mitigated, Gertrude’s spontaneous answers on March 20th (above) — and weakened the motive of jealousy the prosecution was trying to establish as the basis for the murder. Though, frankly, I believe Gertrude’s off-the-cuff answers hold more honesty than those of her relations. I think her family split hairs and told what was technically true in order to keep Gertrude from the gallows.

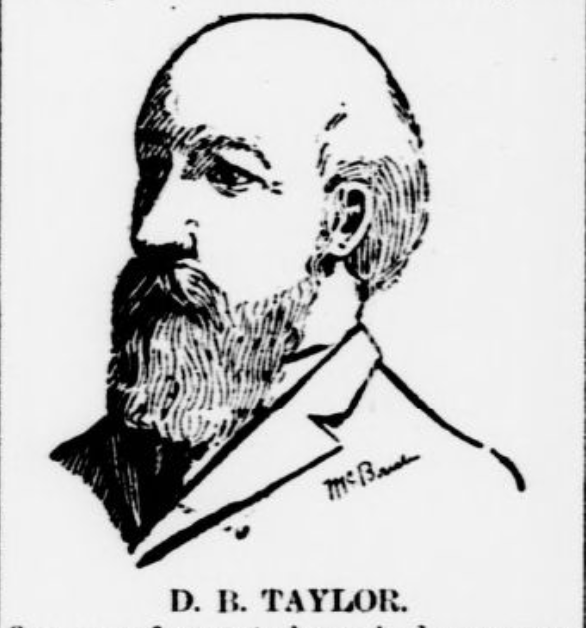

(And yes, I do believe the prosecution would’ve sought the death penalty against the thirteen-year-old — as five jurors were excused from service due to their “conscientious scruples” against a sentence of death. Hauntingly enough, one of the newspaper articles I found advertised that if Gertrude had been anything other than an attractive young girl, the townspeople would’ve lynched her for allegedly murdering Dillon Taylor.

Especially since the townspeople of Craig found Gertrude’s unscripted admission of anger and hate tantamount to a confession. On top of this, Gertrude’s utter lack of emotion and concern at being accused of patricide during her court appearances didn’t help her cause either. A situation Gertrude later remedied by breaking down and weeping whilst on the stand, in front of the all male jury, during her trial.)

In any case, mitigating Gertrude’s motive is all well and good, but her defense needed more. They needed to give the jury an alternate, credible explanation the twelve men could use to find Gertrude not guilty.

The only problem was the classic formula of offering a substitute suspect for the jury to blame wouldn’t work in this case. The only outsider to enter the Taylor home that day was Tyler Cristman, and despite choosing of milk over coffee that evening (the near identical choice Gertrude made, which landed her in the hot seat) — it doesn’t seem anyone ever considered him a suspect in Dillon’s murder. Moreover, during Sarah’s testimony, she stated no one other than Tyler entered their house that day.

Leaving Gertrude’s attorney only the immediate family to offer up in Gertrude’s place….

Speculation on the Baseness of Human Behavior à la Miss Marple: Sex & Money: Interestingly enough, of these two archetypical motives for murder, Sarah owned half of this quintessential duo — inheriting $100,000 worth of land upon Dillon’s death.

As for the sex? Perhaps Gertrude correctly recognized her father’s shift of affection but misidentified from whom they moved. Not realizing, in the throws of egocentric youth, Dillon hadn’t transferred his affections from her — but from his wife to his daughter-in-law? If Dillon and Laura started an affair, it would explain why he refused to relent to Gertrude’s pleas over the organ.

BTW — I’m not pulling this theory from thin air.

While both women possessed the opportunity to put the poison in the coffeepot — Gertrude passed through the kitchen when she returned home from her trip to the drugstore, and Sarah prepared supper that night, alone…It was Sarah who poured everyone’s coffee that evening. An ordinary act that could’ve allowed her to guarantee her husband received a lethal amount of arsenic whilst administering smaller doses to herself and the rest of her family. (Hence why only Dillon died. While Robert & Laura recovered a week later.)

Thanks to Asa Sharp’s testimony, we know he kept a store of arsenic on his farm and used it frequently. This could explain how Sarah got ahold of the dangerous element without linking her name to a purchase record. What’s more chilling? Thanks to the bevy of highly publicized poisoning cases, the rodenticide’s main ingredient was less than secret. So what if Sarah purposely prompted her daughter’s purchase of Rough on Rats? Banking on Gertrude’s youth & good looks, her parent’s influence, and her brothers’ money to get her daughter cleared of all charges.

Can you imagine how wild A.C. & Arthur Sharp would’ve become if Gertrude’s attorney presented Sarah as his alternative suspect? Or Robert? Who, according to his own testimony, was alone in the kitchen when Gertrude arrived home — giving him at least the opportunity to put arsenic in the coffee pot.

As it was, Gertrude’s legal team found an entirely different pretext to present to the jury. In an oddly serendipitous event, one week before Gertrude’s trial started, two farmhands found a box of Rough on Rats right around the area where Gertrude told her Aunt she’d lost it. Not only was the box appropriately weathered, having spent nearly two months exposed to the elements — it still bore the druggist’s wrappings.

This piece of evidence, combined with her family’s measured testimony, allowed the jury to reach a not-guilty verdict in less than two hours.

Leaving Dillon Taylor’s murder, as far as I can tell, unsolved to this day.

An outcome that I find just as insupportable as Sophia Leonides from Crooked House would’ve. Because how can you ever feel safe amongst your nearest and dearest again? Every sugar cookie at Christmas, each pie eaten at Thanksgiving, every piece of candy procured from a family member at Halloween holds a potentially poisonous center — and it’s not paranoia at play here — one of your next of kin proved themselves capable of committing such a dastardly deed.

What’s to stop them from striking again?

What’s to say they won’t follow Josephine Leonides’ example and kill anyone who crosses them? Or years later, they let something slip, panic, and murder again to cover their original sin? What if one of your fam follows Edith de Haviland’s example but gets it wrong? Or someone, eaten up by uncertainty, sends both the innocent and guilty to the grave — just to stop the relentless spiral of anxiety and dread?

Whilst sitting here and writing this piece, I can better appreciate why so many of Christie’s detectives (or people close to them) need to find the culprit in manor house mysteries — which, weirdly enough, the very non-fictional murder of Dillon Taylor neatly slips into. It creates a cloud of suspicion that forever clings to those involved, like so much smoke that not even death can fully dissipate.

Don’t believe me?

What if I were to tell you Robert Taylor committed suicide on March 30, 1930? Now, there’s a myriad of reasons why he could’ve hung himself: depression, familial estrangement (in 1889, two years after Gertrude’s trial, he sue his mother and siblings – including his 6yr. old sister Nancy, — for what I don’t know, but it doesn’t speak of happy families), or cancer diagnosis (a disease that claimed his younger brother Duke’s life nine years later).

But doesn’t a tiny part of you wonder, after thirty-four years and twenty days, if his guilty conscience finally caught up with him?

As for Gertrude, she married sometime around 1900-1901 to a man named Marcus Spencer. They had a daughter about 1903 and another two years later. Gertrude was widowed on August 30, 1915, after her husband died of TB (a disease which, apparently, killed his two sisters and brother before him). Gertrude herself passed away on September 12, 1958, from a cerebral thrombosis at the age of 76.

And, despite all my research, I am none the wiser to who actually murder Dillon Taylor. I lean toward Gertrude, but really her original indictment is based solely on Dr. Kaltenbach’s misgivings and one imprudent interview. And, as we’ve seen in other cases, we don’t know how closely the police looked at the other people seat at the supper table on March 10, 1896….

Leaving open the possibility someone other than Gertrude assassinated Dillon Taylor.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.