My 52 Weeks With Christie: A 2022 Revisit to The Pale Horse Part 1

The Pale Horse by Agatha Christie

Word of Warning: If you haven’t read Christie’s The Pale Horse, proceed at your own risk, as this write-up contains spoilers. I’ll try and mitigate them if I can….but in covering what I want to cover in this piece, there isn’t a good way of avoiding plot points. So if you’ve already cracked this book’s cover or don’t mind having critical elements of the mystery revealed before you pick up the story — read on!

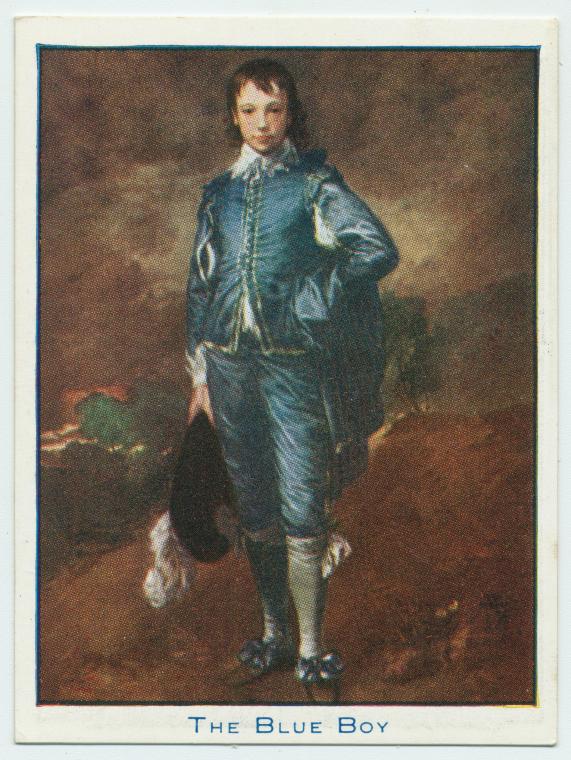

The 2022 Follow-Up: Ever since I first read The Pale Horse, all the way back in 2014, I’ve wondered how on earth someone came up with the idea of administering Prussian Blue to people suffering from Thallium poisoning. It seems improbable that a scientist would stare at Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy and think — ‘Hey! I bet that deep blue pigment would make a great antidote for heavy metal poisoning.’ However, other than the occasional idle thought, I never did much of anything to answer my own question.

(BTW — This photo of a photo does not do the painting justice.)

Until our house insisted we needed to replace all its pipes, water heater, and sewer line.

Turns out writing fiction, for me, doesn’t work so well when you’ve got a pair of plumbers wandering all over and under your house banging, clanging, and sawing holes in your walls.

Who knew?

And, for whatever reason, this long-neglected Prussian Blue colored question popped into my head again — and needing a distraction from the crew digging up my flower beds (for the second time in as many weeks), I began my search in earnest.

In fairness, I didn’t actually nail down how scientists landed on Prussian Blue as an antidote. So it’s possible that the inspiration stick struck them whilst watching the blue ink flow from their fountain pens. (Assuming they owned such writing implements, favored blue ink above black, purple, or green, and knew Prussian Blue is a component of the ink’s recipe.) However, it’s not probable.

And yet….

The very first bucket of Prussian Blue was an accidental creation. Thallium was discovered by two scientists, independently of one another, at nearly the same time. So there is precedent for unlikely coincidences occurring.

Unfortunately, the same serendipity did not strike when I Googled ‘Who discovered Prussian Blue was an antidote for Thallium poisoning’. (That would’ve been entirely too easy.)

So down the rabbit hole I leapt, looking for answers — beginning my quest with Prussian Blue.

As told by Georg Ernst Stahl, Prussian Blue’s origin story places the pigment’s synthesis at the door of color maker Johann Jacob Diesbach. Working in a shared Berlin lab in 1704, Diesbach initially set out to create a red hue. The only problem was he’d run out of a key ingredient, potash. Borrowing some of his lab-mate, Johann Konrad Dippel, Diesbach continued mixing the formula — unaware that Dippel’s potash was contaminated with animal material. When Diesbach finished his mixture, rather than creating the anticipated red, he’d accidentally concocted Prussian Blue for the first time.

Here’s where things get a bit murky.

Apparently, Stahl wrote his account twenty-five years after Diesbach’s discovery. Since then, a series of letters from Johann Leonhard Frisch and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz have come to light (two eminent scientists of the day). Whilst these primary source materials seem to confirm Diesbach as Prussian Blue’s inventor — Frisch later declares Prussian Blue as his own invention. An assertion undoubtedly rooted in Frisch’s claims to have improved upon the original color and lowered its manufacturing costs. There’s also a good chance Frisch was trying to save face with this boast — as Diesbach’s father-in-law informed Leibniz of Prussian Blue’s actual creator.

(Fun Fact: Even back in the day Leibniz was a BFD. Amongst his other achievements: he’s considered one of the most important people in the history of both math and philosophy — and — whilst overseeing a German library created a method for cataloging books that influenced other libraries all over Europe. Hence why someone might tell a lie in order to impress this very impressive man.)

Either way, Diesbach and Frisch only managed to keep Prussian Blue’s formula a secret (allowing both men to cash in) until 1724, when John Woodward published a Prussian Blue how-to recipe. Thereby allowing manufacturers to flood the market with variants of this iconic color.

Crucially to my Pale Horse inspired inquiry, Woodward’s verified formula enabled other scientists to research Prussian Blue’s chemical properties. In the hopes of nailing down its composition, stoichiometry, and structure.

Unfortunately, this is where the trail went cold, and the plumbers discovered our sewer pipe needed lining because it was older than Methuselah. (*sigh*)

Other than uncovering Carl Wilhelm Scheele’s talent for concocting toxic substances. None of the distinguished chemists or alchemists of the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries figured out Prussian Blue’s exact structure or that it was an antidote for thallium.

Unwilling to give up, especially since the plumbers added another week of plumbing fun to the agenda, I started tugging a different line of inquiry.

A.Miner©2022

You must be logged in to post a comment.