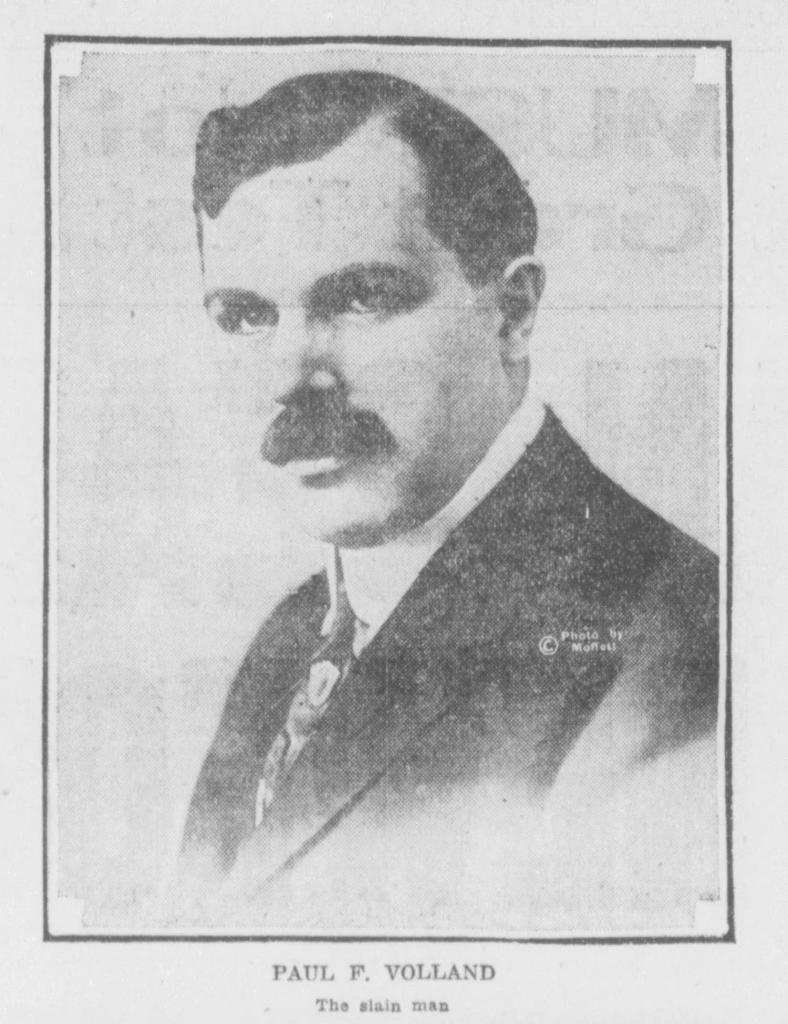

The Paul F. Volland Company published some Raggedy Ann stories, as well as, the New Adventures of “Alice” based on Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

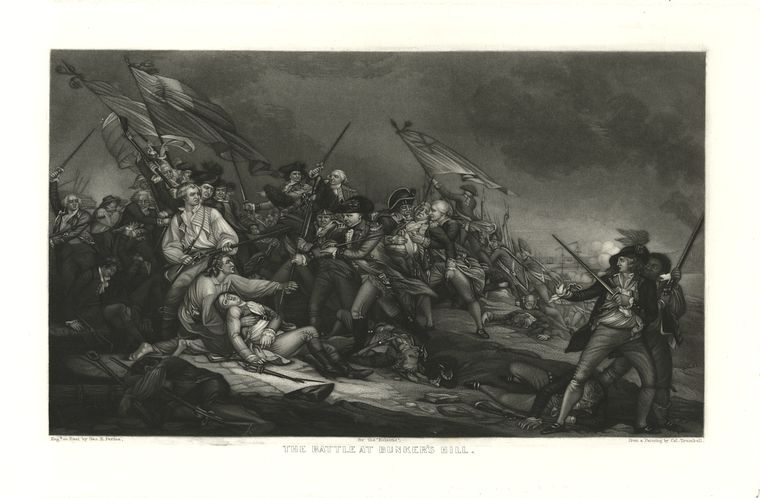

Let’s be clear: I believe Paul F. Volland pulled a bait-and-switch on Vera Trepagnier. I think he used his position as President of the P. F. Volland Company, his business acumen, and knowledge of Vera’s strained circumstances to his advantage in order to obtain and keep the Trumbull portrait of George Washington. By dangling the promise of $5,000 before Vera, Volland gained possession of the painting. Next, by carefully wording the contract, he — not his company — secured ownership of the diminutive object if sales of the reproduction reached the 5k mark. If said sales didn’t pan out, which he was in the perfect position to ensure, Volland could point at the $500 advance and issue an ultimatum — either accept it as payment or repay the shortfall in a lump sum. Secure in the knowledge she couldn’t.

The fact he didn’t maintain contact with Vera, nor had his lawyers issue said ultimatum until Vera made it patently clear she would continue to pester him for forever and a day, is why I’m inclined to view his actions under a crooked light. Because without that $5,000 promise, I don’t think Volland could’ve pried that painting out of Vera’s hands. (And I don’t see him giving Vera $500 as a charitable act.)

Examples of the fancy postcards printed by the P.F. Volland Company.

The question is, why would a wealthy man bilk a widow? The only concrete reason I found that might, and I mean might, explain such behavior occurred a few years before Volland’s death: When he nearly declared bankruptcy. Ultimately, Volland didn’t. But perhaps after skating so close to financial ruin, it invoked an unscrupulous or miserly side to his nature? Or maybe he grew up unable to rub two nickels together, which left him unwilling to pay a penny more for anything when he didn’t have to. Or perhaps he was just crafty.

It’s unclear.

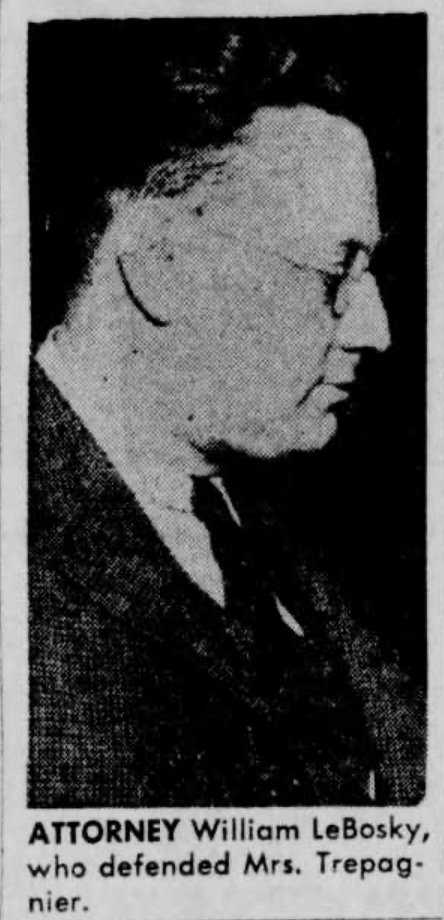

Interestingly, Vera’s charge of sharp business practices against Volland wasn’t the only one I found. A female musician contracted to write some sheet music for the P. F. Volland Company claimed that after Volland rejected her song, he later published it under someone else’s name without her permission or paying her for the work. What’s more, the day after Volland’s death, Chicago artists announced their intention to raise funds for Vera’s defense…..Again, this makes me wonder how fair Volland played with others when wheeling and dealing.

Unfortunately for Vera, partaking in dodgy business practices doesn’t automatically translate into owning a violent streak. (Nor does it mean he deserved to die.)

Other than stating she used a revolver, I’ve no clue the type of firearm Vera used, so here’s a gun advert from 1913. (And yes I know this is not an ad for a revolver.)

This begs the question: Why did Vera feel the need to bring a gun with her to discuss a dispute over a contract? According to the woman herself, “I took the revolver along to scare him. I had no intention of killing him, but that was done when he tried to take the weapon away from me.” An explanation I find believable. What I find harder to swallow is Vera’s claim the one and only day she packed the piece in her purse was the afternoon she accidentally shot Volland.

As I see it, either the stars aligned and allowed Vera to seize an unexpected opportunity to lie her way into Volland’s presence — OR — Vera stalked Volland long enough to know he’d be in his office that particular day. If Vera relied on the ‘universe’ to provide her with an opportunity to enact her desperate plan, then it stands to reason she’d bring the gun along with her daily. Otherwise, how would she have it on hand precisely when she needed it? The latter stalking explanation, which Vera admitted doing, is the only way I see the ‘I only brought the gun with me once’ course of events as plausible. The problem there is it smacks of premeditation.

Either way, neither version of events paints Vera in glory.

More importantly, by bringing the firearm with her, Vera cast herself into the role of instigator, severely undermining any claim of self-defense, crime of passion, or the ‘unwritten law.’ The prosecution weakened Vera’s claim further when they labeled her a blackmailer, presenting at least one nasty letter Vera wrote threatening to ruin Volland’s reputation by exposing his manipulative business practices — lest he make good on their deal.

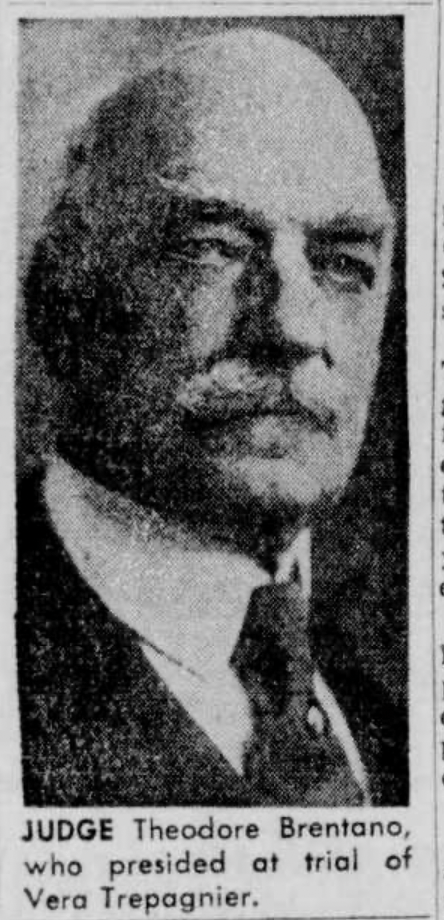

Without any other testimony (from, for instance, another firearms expert to refute the prosecution’s, a psychiatrist willing to declare Vera mentally unsound at the time of the murder, or anyone who could attest to Vera’s erratic behavior) to mitigate the prosecution’s arguments, Vera’s lawyers only managed to convince one juror out of twelve to find Vera not-guilty. (And he changed his mind by the second ballot.)

Hence why, I feel Vera’s lawyers did her a disservice.

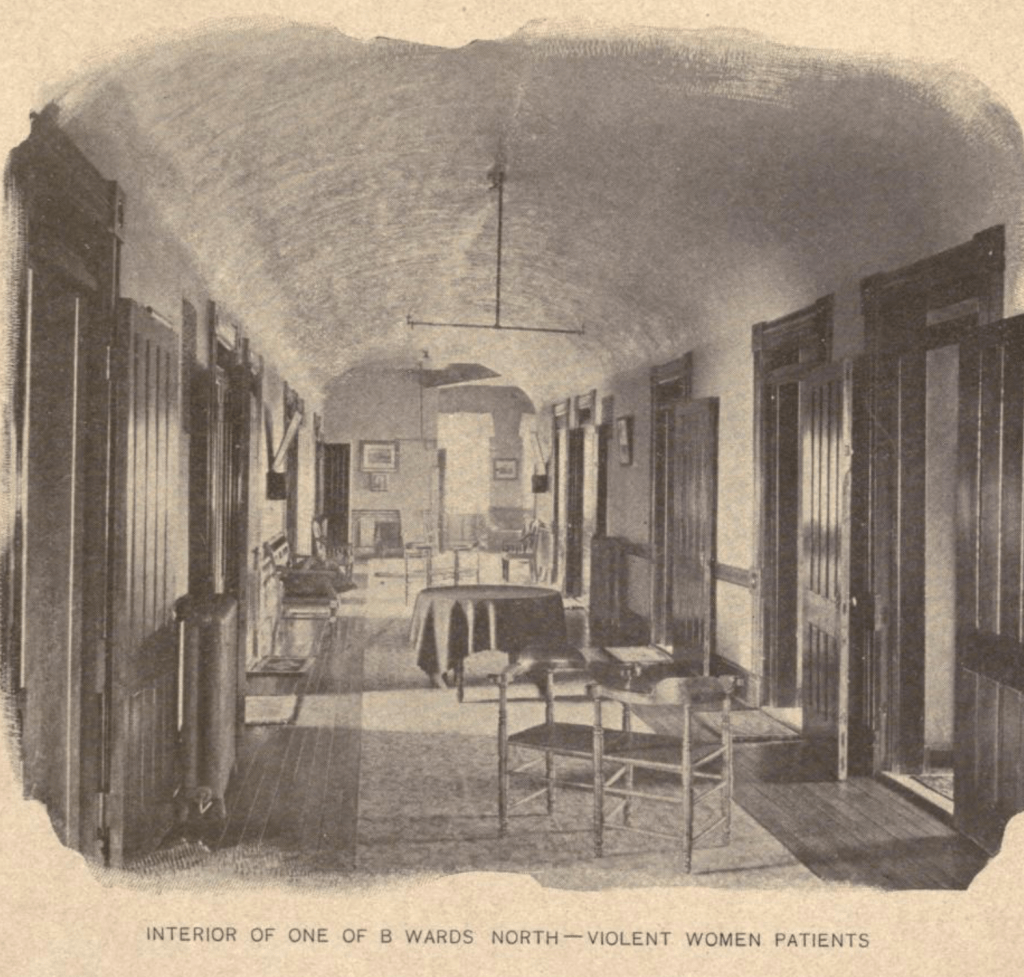

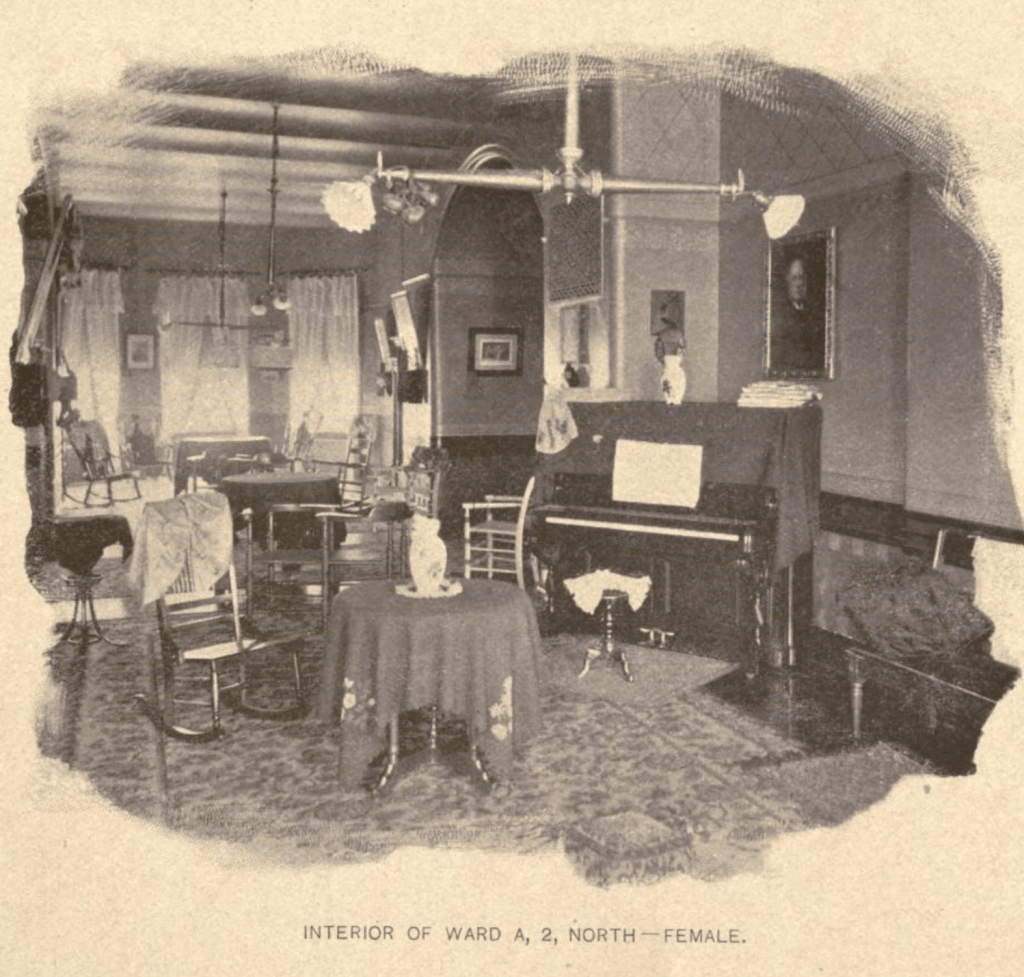

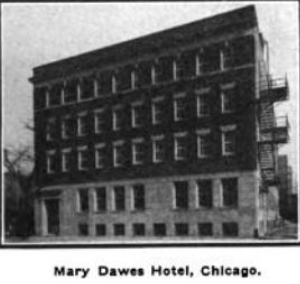

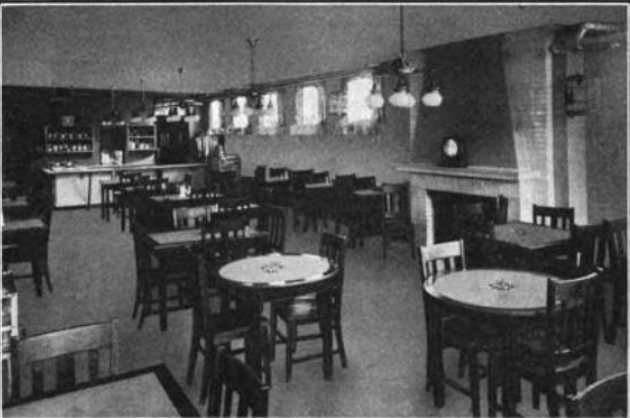

Interior photos of the women’s spaced at Kankakee State Hospital from sometime around 1900.

What happened after the guilty verdict? After Vera’s appeal for a new trial was denied in August 1919, she was transferred to Joliet State Prison to serve her sentence of one year to life. Sadly, at some point after September 1, 1920, Vera was transferred to Kankakee Insane Asylum. According to prison officials, the loss of the Trumbull’s portrait of George Washington (and probably the stress of the trial and incarceration) “unhinged” her mind — causing Vera to speak dreamily of nothing but her former prized possession to anyone willing to listen.

Vera would die within the asylum walls on August 19, 1921.

In her will, Vera left several tracts of land in Maryland, a vase, and the Trumbull miniature to her grandson. Sadly, Vera forgot the vase had already been donated to a museum in New Orleans, so it wasn’t hers to give. And Vera’s only son sold the tracts of land to cover an overdue mortgage.

As for the Trumbull miniature, an attorney by the name of Michael F. Looby was assigned by a probate court to sell it — which made quite a splash in the papers. Assured by art experts, museums, and collectors that ‘Exhibit A’ would fetch anywhere between $5,000 and $30,000, it went to auction. On September 23, 1922, Looby returned to Judge Horner’s courtroom and reported that due to the unpleasant notoriety attached to the painting, the highest bid received was $325.

Whereupon Judge Horner approved the sale — to persons unknown and it disappeared from public view.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.