Genevieve Forbes did some great writing, but when it came to Isabella? To put it nicely, which is more than she did for Isabella, Genevieve was a sourpuss (as my grandmother would say).

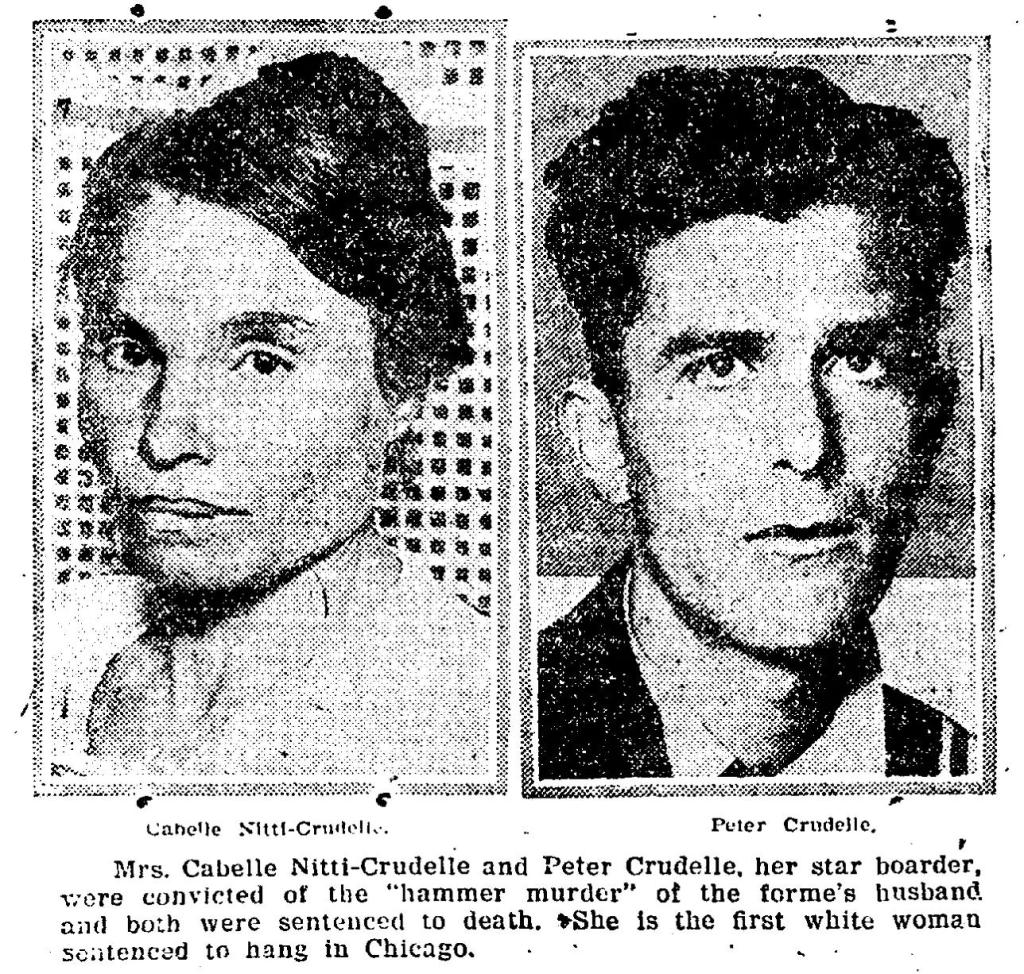

In early July 1923, Isabella Nitti-Crudelle and Peter Crudelle went on trial — pleading not guilty. Whereupon, Isabella drew some singularly harsh criticism from Genevieve Forbes, a prominent female reporter who covered the crime beat for the Chicago Tribune.

Forbes took exception to basically everything about Isabella, calling her: “…dumb, crouching, animal-like Italian peasant” and “…dirty, disheveled woman…” amongst other derogatory terms. Other reporters picked up this language, calling Isabella: “Dumpy and squat and with no redeeming gift of grace, the dumb-like little peasant woman….creature of primitive physical instincts…mussy twisted hair and swarthy brow so seamed and crinkled with premature marks of age….leathery face and warped figure…”

A couple of the unflattering photos & drawings of Isabella used by a NUMBER of papers – and – a blurb “explaining” why the jury ruled the way they did.

These dehumanizing descriptions go on and on and on.

By referring to Isabella in such terms, Forbes and the others of her ilk painted Isabella as subhuman and undeserving of compassion, sympathy, or mercy from their readers or the jury. Moreover, by focusing on Isabella’s southern Italian heritage, language, and mannerisms — Forbes tapped into the anti-immigrant sentiment of the day (as exemplified by the Immigration Act of 1924, crafted by a fan of eugenics and a man who thought the US needed a Mussolini type leader to pull the country out of the Great Depression). Which only increased Isabella’s status as unworthy of the leniency shown to the bevy of other accused murderesses who’d come before her.

Unsurprisingly, Isabella and Peter (who’d practically become a footnote in the newspaper coverage of the crime) were convicted of Frank’s murder and sentenced to hang on October 12, 1923. A punishment that caused a sensation across the country, as Isabella was only the fourth woman ever to receive a death sentence in Illinois.

While most believed Illinois’s Governor Len Small would commute Isabella’s death sentence to life in prison, which had been done for the two other women before Isabella — it wasn’t a sure thing. In 1845, Illinois’s Governor Thomas Ford failed to intervene on behalf of Elizabeth Reed, who’d hung after being convicted of poisoning her husband. Above and beyond Illinois’s single female execution seventy-eight years earlier, there’d been an uptick around the world of female death sentences being carried out: Dora Wright (1903 Oklahoma), Mary Rogers (1905 Vermont), Mary Farmer (1909 New York), Virginia Christian (1912 Virginia), Pattie Perdue (1922 Mississippi), and, across the pond in England, another cause célèbre murder case resulted in the hanging of Edith Thompson on January 9, 1923.

Even more worrisome, Isabella’s conviction failed to stem the flow of dehumanizing remarks. Many of the reports after Isabella’s date with the hangman was announced made it sound as if Isabella was grateful for her confinement on Murderess Row: “….she seems thankful for the better jail fare with occasional time for play, recreation, and with no worry now for poverty nor endurance of bitter cold.” Whether these comments were meant to assuage the public’s guilt over the state’s mandate of death or to make her execution sound akin to mercy is unclear. What we do know is Isabella was terrified. Alongside these reports of Isabella’s “gratefulness” were stories of her enduring panic attacks, obsessive cleaning & singing (undoubtedly done to try to keep her mind occupied), and at least two suicide attempts.

Thankfully, not everyone shared Genevieve Forbes’s point of view.

After the death sentence was handed down, one juror’s wife threatened to leave him if Isabella hanged. Another group of women bent on obtaining Isabella’s freedom took Forbes to task for her attacks on Isabella’s appearance and character. Unsurprisingly, Forbes mocked their rebuke in print and labeled their efforts to free Isabella as: “…women’s primitive loyalty to a forlorn sister, down and out, and homely.”

Crucially, besides gaining the sympathy of women around the city and the support of those opposed to the death penalty under any circumstance — Forbes’s inhuman rhetoric and reports of the trial itself inspired five Italian American lawyers (Swanson, De Stefano, Bonilli, Mirabella, and Helen Cirese) to step in and take Isabella’s (and Peter’s) appeal on pro bono.

First, the legal team took aim at the circumstantial evidence used to convict: Identification of the body — which rested on a single ring, the inconsistencies between Charles Nitti’s confession and the state’s evidence (where he said the body was dumped in a river, yet the body identified as Frank’s was found in a catch basin), and the fact there was another suspect with plenty of motive whose identity was deemed inadmissible during the trial.

However, the main thrust of the quintet of lawyers’ appeal rested on the absolutely abysmal defense mounted by Isabella and Peter’s former trial lawyer, Eugene A. Moran who, the Illinois Supreme Court would later say, “….It is quite clear from an examination of the record that the defendants’ interest would have been much better served with no counsel at all than with the one they had.”

For example: Despite securing a translator who spoke Barese, the Italian dialect Isabella spoke, Moran exchanged very few words with her prior to stepping into the courtroom — so how could she aid in her own defense? Moreover, during Moran’s cross-examination of Isabella and Peter, he repeatedly asked them questions that could’ve led them to incriminate themselves on the stand. Apparently, it got so bad that at one point, the trial judge stepped in, warning Moran he was harming his client’s defense. (A caution which didn’t alter Moran’s behavior a whit.)

(BTW: Before we paint Moran in villainous colors, according to a couple of recent articles/blog posts, he’d started suffering from some sort of mental health problems around this time. Which could account for this subpar court performance. Though I’ve been unable to verify this information, I thought it worth mentioning.)

Taking all these legal points under consideration, on September 26, 1923, Justice Orrin N. Carr stayed Isabella and Peter’s execution until their appeal could be presented to the Illinois Supreme Court in February 1924.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.