(Obviously this isn’t a map from 1898.)

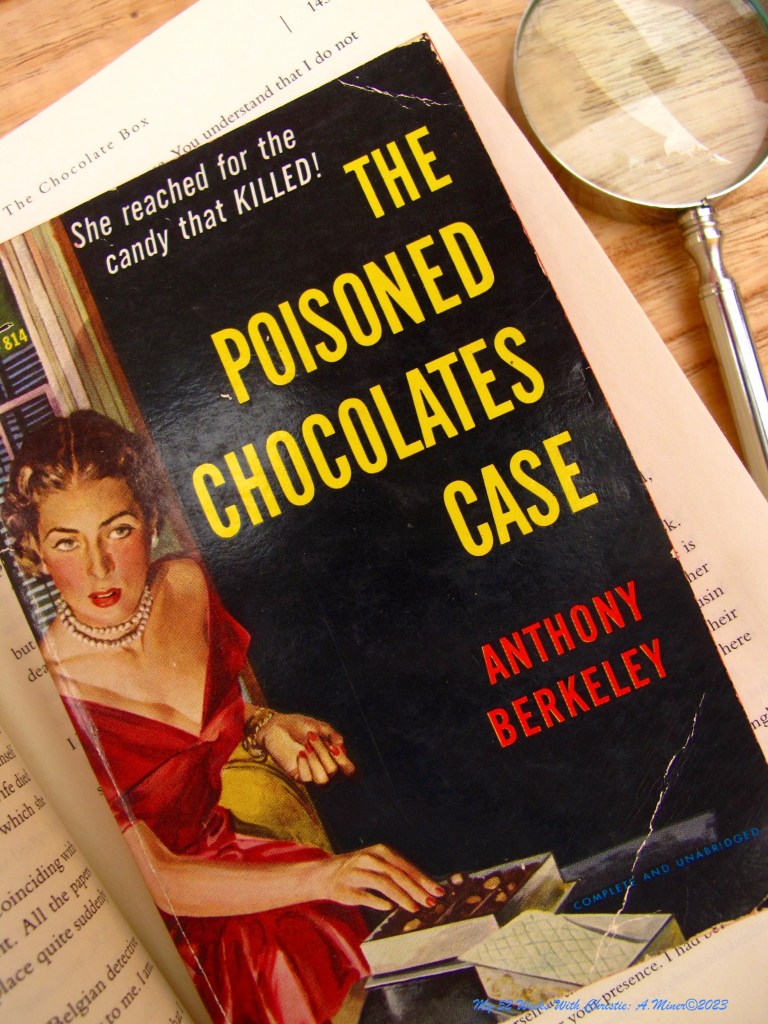

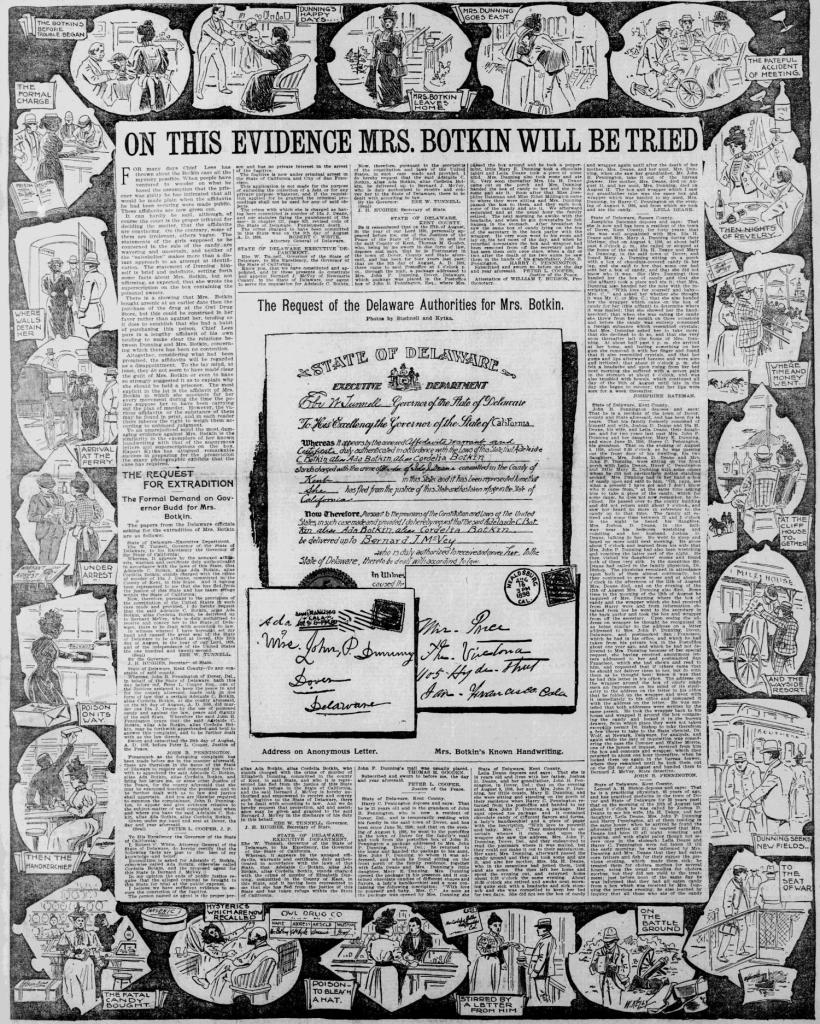

Continuing on our theme of unexpected deliveries, tainted sweets, and copycats of Cordelia Botkin (who murdered two women by sending poisoned chocolates through the mail), we are going to put St. Louis (Mo.), Florence McVean, and her sister Mary McGraw in our review mirrors and travel roughly five-hundred-and-twenty-six miles northwest to Hastings, Nebraska to meet Viola Horlocker.

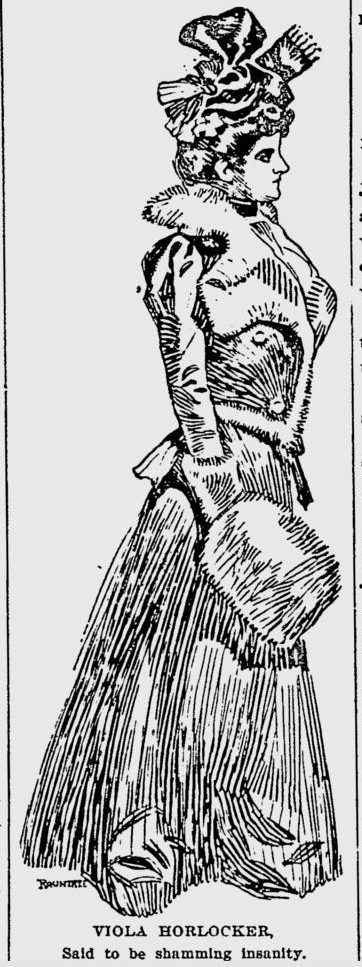

Known as Ollie, though I will continue to refer to her as Viola for constancy’s sake, she was the second oldest of four sisters. By the spring of 1898, all save Viola had left home. The oldest, Luella, became a highly regarded painter of porcelain china. Lita went on to become an accomplished artist in the field of flower painting and arranging. Whilst Zora made a name for herself as a professional singer. Like her sisters, Viola also possessed a musical streak, which she showed to full advantage by singing and arranging music for the church’s choir. Though not considered a beauty, Hasting’s society did find Viola attractive, fashionable, and “well above mediocrity in every way”.

However, things weren’t as rosy as they appeared at first blush.

Viola’s father, George, not only made and lost a vast fortune, he also abandoned his entire family when Viola was a teenager. An event that surprised no one in the community, as next-door neighbors were often treated to the auditory splendor of knock-down-drag-out fights between the Mr. and Mrs. of the Horlocker household. (At one point, during one of these vicious rows, said neighbors felt the need to intervene. Upon locating the source of the commotion, they found Mrs. Horlocker beating George with a pot about the head and shoulders in the kitchen. Noting the number of dents in the cookware, neighbors surmised this wasn’t the first time something along these lines happened.) After her husband’s hasty exit stage left, Mrs. Horlocker turned her capricious temper, bitter disposition, and sour tongue on her daughters. Driving each and every one to seek out respectable employment in cities hundreds of miles away from their mother.

Save Viola.

Viola stayed behind to cope with a maternal figure, who was not mellowing with age, alone. Again, this turn of events wasn’t wholly unexpected. Viola’s sense of duty to her family found her stepping up to provide for her mother and two younger sisters (as Luella was already out of the house and state by this point) after their father departed. Educating herself in the law, Viola worked as the deputy county clerk for four years until she accepted a position at Tibbets Bros. & Morey. Where her work was considered exemplary. (There is a bit of discrepancy regarding her exact role in the firm. The newspapers labeled her a stenographer. However, during the trial, the Tibbets brothers said Viola drew up flawless legal documents for them….Which sounds more involved than what a stenographer normally does? I’m not really sure. Though, it wouldn’t be the first time newspapers of this era chose a dumbed down a woman’s job title to avoid confusing their readers.)

Enter Charles F. Morey.

Prior to joining the prestigious firm as a junior partner, he’d held the office of City Attorney for years. Now, it’s unclear if Viola and Charles knew each other before joining the same firm, but either way, they soon became acquainted — as Viola was assigned to assist him. By the time spring rolled around in 1898, the two were friendly enough that Charles introduced Viola to his wife and tried to encourage a friendship between the two women. He also invited Viola to join his cycling club….Naturally, Charles accompanied Viola home after each meeting or tour — to make sure she arrived safely.

Fast forward a few months to the summer of 1898: Anna, Charels’s wife, left Hastings for a few months.

Almost immediately, Charles and Viola started spending ever increasing amounts of time together. They’d go for long, winding rides in the country, where Charles confided in Viola about his work, career aims, and struggles at home. Viola, in turn, vented to Charles about her troubled home life and mercurial mother. Charles then began asking Viola to stay on after everyone else in the office left for the day, for more long talks, which more often than not spilled over into dinner at one restaurant or another. If Viola felt she couldn’t leave her mother alone on a particular evening, Charles would accompany her home, and they’d sit out on her porch for hours talking.

After three months of this constant association, the local newspaper’s gossip column weighed in on what the Hasting’s busybodies had already started whispering about: What would Anna say if she knew her husband was spending such copious amounts of time with his young female law clerk? As they say: While the cat’s away, the mice will play. Though the paper didn’t print their names, everyone in Hastings knew (or was subsequently informed of) who the couple in question was. This potentially embarrassing situation prompted one of the Tibbets brothers to pull Morey aside and advise him to cool it with Viola.

Counsel Charles willingly complied with as his wife was due home in days.

To say Viola took Charles’s news badly would be an understatement. However, she soon learned no amount of protestation or pleading would alter Charles’s mind. He even went so far as to have Viola reassigned to one of the Tibbets, further limiting Viola’s opportunities to spend time with him. And whilst her work didn’t suffer, after Charles dropped her like a hot stone, her manner did. Over the subsequent fall and winter months, Viola’s demeanor turned increasingly irritable, nervous, and depressed….

Until everything came to a head on April 10, 1899.

According to the newspapers, the bare bones of the “incident” went something like this: Whilst Charles occupied his days with lawyering. His wife Anna added to the household coffers by teaching art, drawing, and painting to the well-to-do women (and their daughters) of Hastings. And by all accounts, both Anna and her classes were remarkably popular. Due to the duo’s demanding professional calendars, Charles and Anna chose to consciously carve out time to spend together.

One such hewn event was a standing Monday lunch date at the Boswick Hotel.

On this particular April day, after finishing their meal and parting ways until quitting time, Anna rushed home to prepare for a class. When she arrived at their apartment’s door, Anna found a box of candy sitting on the mat. The attached card identified the gift giver as one of Anna’s good friends, Miss Kirby. Still needing to zoom, Anna Morey set the box aside and started prepping her studio for the impending art class. A short while later, with everything sorted and five out of six students on hand, Anna opened the box of homemade candy. Passing the sugared walnuts and cherries around, the group partook while they waited for the last class member.

(Okay, these aren’t the candied varieties, but you get the drift. Thanks to Joanna Kosinska & Tom Hermans & Unsplash for these photos.)

Who, in an odd case of serendipity, just happened to be Miss Kirby.

Upon Anna’s thanks for the unexpected box of sweets, Miss Kirby denied making or sending Anna the candy. Unsurprisingly, this contradiction frightened everyone: The notorious trial of Cordelia Botkin had only wrapped up five months prior and copycat crimes, like Florence McVean’s, had proliferated on newspaper’s front pages across the country ever since.

Compounding this disquiet, everyone who’d nibbled on a piece or two or three — started feeling queasy. Uncertain whether the power of suggestion or something more diabolical was causing their gastric distress, the group of budding artists sent for a doctor….Who, after arriving, rapidly determined he’d a genuine case of poisoning on his hands. After treating/stabilizing the group of women, the doctor sent the remaining candied fruit and nuts out for testing.

The very first piece tested came back as containing four grains of arsenic.

Now, if I understand how this largely defunct unit of measurement works (please correct me, nicely, if I’m wrong), one grain equals just a smidge under 65mg. Experts consider a lethal dose of arsenic between 100-300mg (depending on things like body mass, tolerance, and overall health). So if each piece of the tainted candy contained four grains or about 258mg of arsenic…..That sextet of women should thank the gods above and below for escaping the afternoon of April 10th with their lives. Anna Morey, in particular, should light a candle. The only reason the tainted sweets didn’t kill her outright was that she threw up a large measure of the arsenic she’d eaten. As it was, Anna was bed-bound for weeks afterward as the toxic substance worked its way out of her system — her husband continuously by her side.

News of Anna’s mysterious poisoning spread like wildfire through Hastings.

Two days after the ‘incident’ Viola, who’d continued to work diligently at the firm whilst gossiping with everyone else over nearly fatal turn of events, ran into a family friend at the drugstore. Well acquainted with the gossipworthy happenings betwixt Charles and Viola the summer before Dr. Cook voiced his growing suspicion: “Ollie, how could you do this?”* To say this brought their conversation to an abrupt end is an understatment, as Viola apparently fainted then staggered away from the good doctor as fast as humanly possible after regaining her senses….Then, later that same evening, she and her mother boarded an eastbound Burlington Train and left town.

Because running away after someone accuses you of attempted murder ALWAYS makes you appear innocent.

*(There’s a variant of this story where one of the Tibbets Brothers accuses Viola. However, the majority of the newspapers printed the Dr. Cook version.)

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.