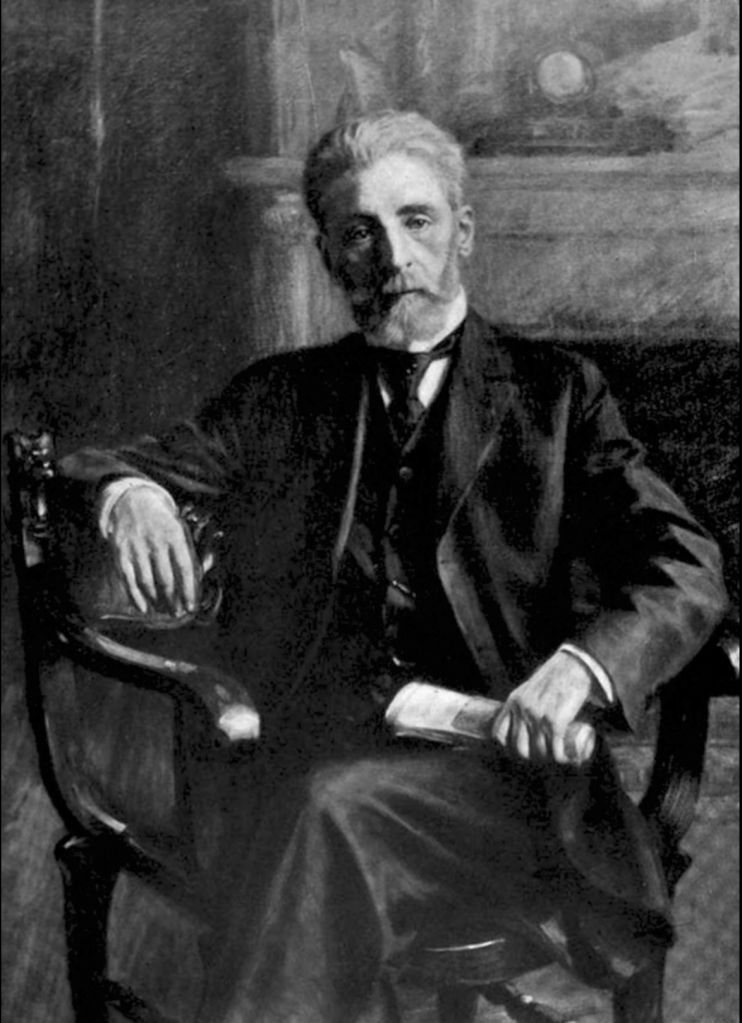

Okay, so here’s the thing, before I go into the last feature of interest of Louisa Lindloff’s murder trial, we need to take a closer look at her lawyer, George Remus.

About seven after Louisa Lindloff’s trial: George relocated to Ohio and remade himself into a Prohibition-era rum-runner — after realizing how much more money he could make being a bootlegger versus defending them in court. Using his skills as a former pharmacist whilst applying his law degree, Remus found/utilized a loophole in the Volstead Act to make millions from both legitimate and illicit whiskey sales.

Predictably, the King of Bootleggers’ business plan rapidly pinged the police’s radar.

On May 17, 1922: George was found guilty of violating the aforementioned Act and sentenced to two years in Atlanta’s federal prison.

Now, according to George Remus, this is what went down next: While serving his sentence, Franklin L. Dodge Jr., an undercover prohibition agent, managed to prise from George the information that he’d given his second wife, Imogene Holmes, power of attorney over his dream home, vast fortune, and bootlegging operation. (George’s first wife divorced him after discovering he was carrying on with Imogene on the side.) However, rather than reporting this juice tidbit to his superiors, Franklin supposedly resigned his post and promptly seduced Imogene.

At this point, the pair proceeded to liquidate George’s personal and professional assets. Secreting away the resulting money from both the government and George.

Understandably fearful of retribution, Imogene and Franklin began plotting. First, Franklin attempted to persuade his former colleagues to deport George back to Germany, where he originally hailed from. When that scheme crashed and burned, the two turned to violence and hired a hitman. However, said assassin, apparently afraid of being double-crossed, kept the $15,000 fee and briefed Remus about the plan instead.

Fully aware of George’s mounting fury and at wit’s end, Imogene and Franklin went into hiding. Unfortunately, this strategy conflicted with the divorce proceedings Imogene initially filed for on August 25, 1925 (two days before George was released from Federal Prison). Due to several lengthy delays, the dissolution date was finally set for October 6, 1927.

A few hours before she was due in court, Imogene and her teenage daughter (not fathered by George) left their Cincinnati Hotel and hailed a cab. On her way to her lawyer’s office, Imogene spotted George and his chauffeur following them.

When traffic unexpectedly slowed to a crawl around Eden Park and/or George’s chauffeur forced the cab into the parking lane (it’s unclear from what I read which way it happened), Imogene panicked. Leaving her daughter in the relative safety of the cab, Imogene hopped out and fled into the public park. Unwilling to let his quarry flee, George flew from his ride whilst shouting four-letter epithets at Imogene’s retreating form.

In short order, George caught up with his estranged wife and, before anyone could intervene, George shot Imogene in the abdomen. A wound she would die from the same day, despite being rushed to hospital by good Samaritans and surgeons doing their level best to save her.

Obviously, George went on trial for Imogene’s murder.

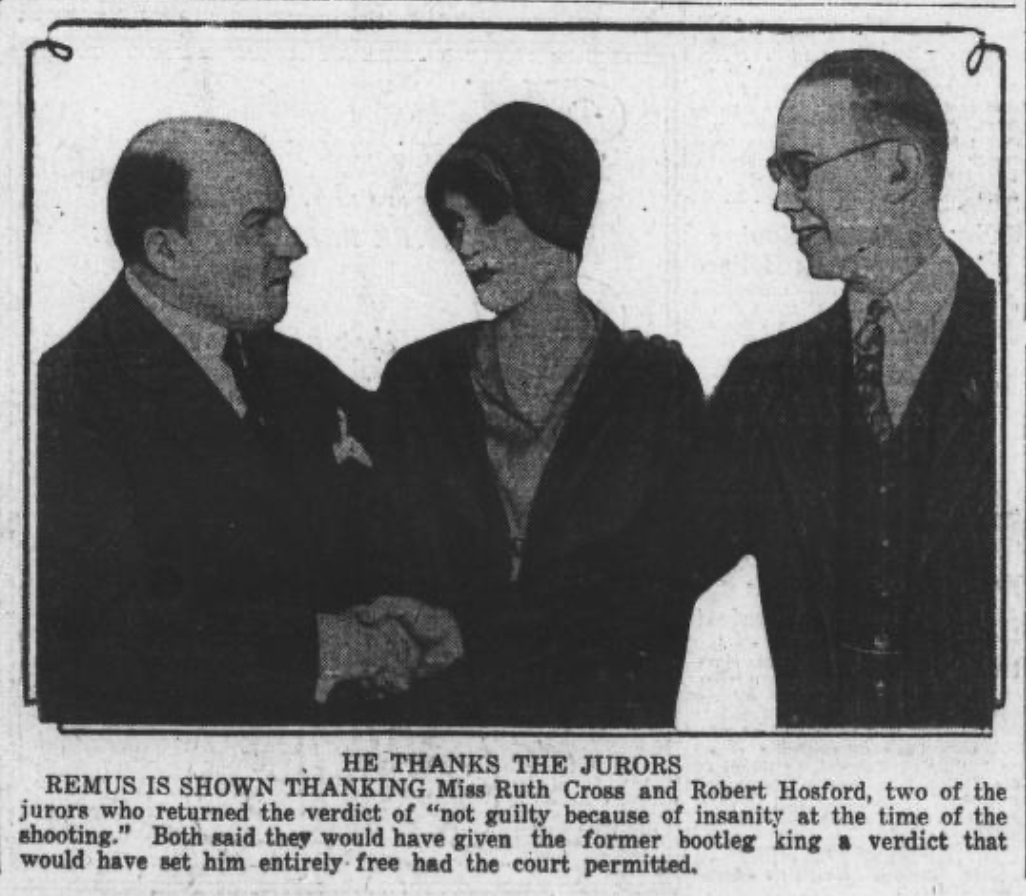

Using ‘temporary insanity’, a defense George helped pioneer, he and his lawyer managed to secure a not-guilty by reason of insanity verdict. Though Ohio authorities committed him to a state-sanctioned asylum afterwards, George would only stay within its walls for a few months before being released. And, due to the ASA’s arguments during his trial, the courts would not allow the state to retry George for Imogene’s murder — leaving him free as a proverbial bird. (George would later go into real estate, marry his secretary, and die in 1952.)

Now, what does George’s sins have to do with the price of maple syrup in Canada?

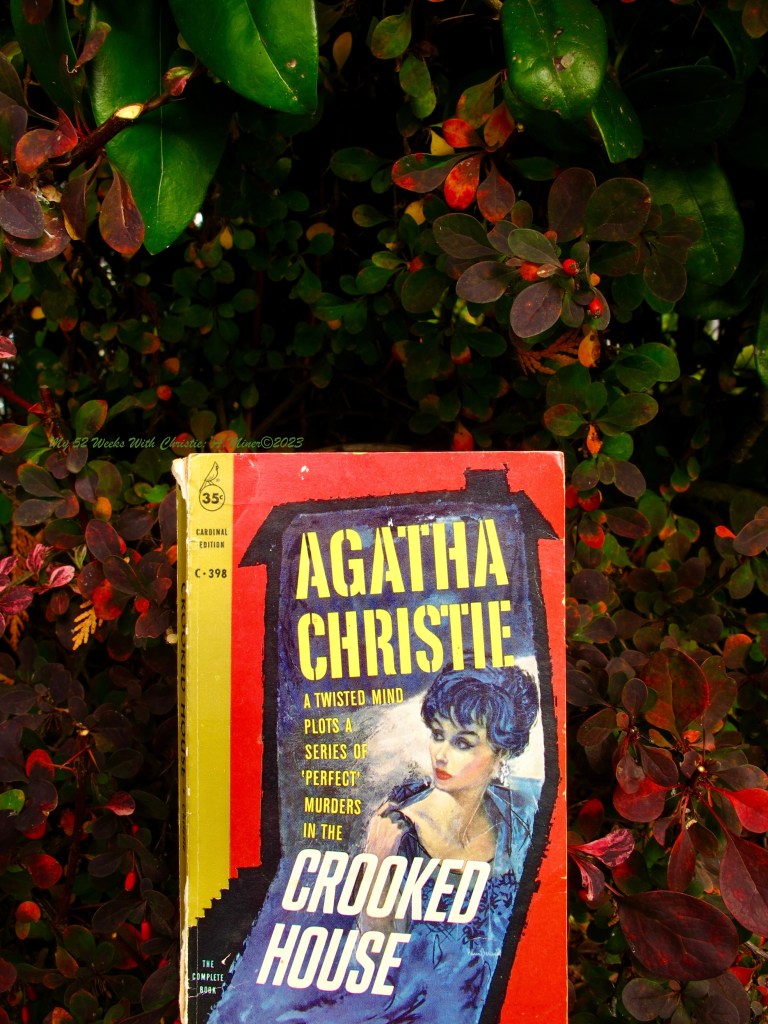

Well, in my estimation, it shows a degree of ethical elasticity. An understatement in light of Imogene’s murder, I know, but up until that point, it seems George was content following the same crooked path as Aristide Leonides.

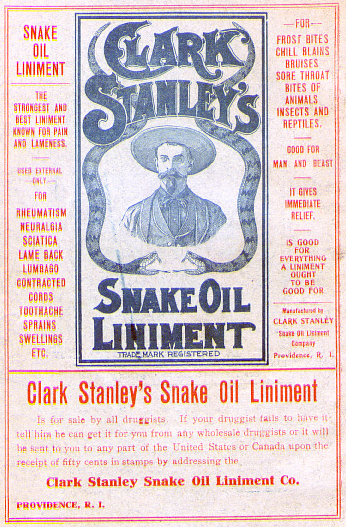

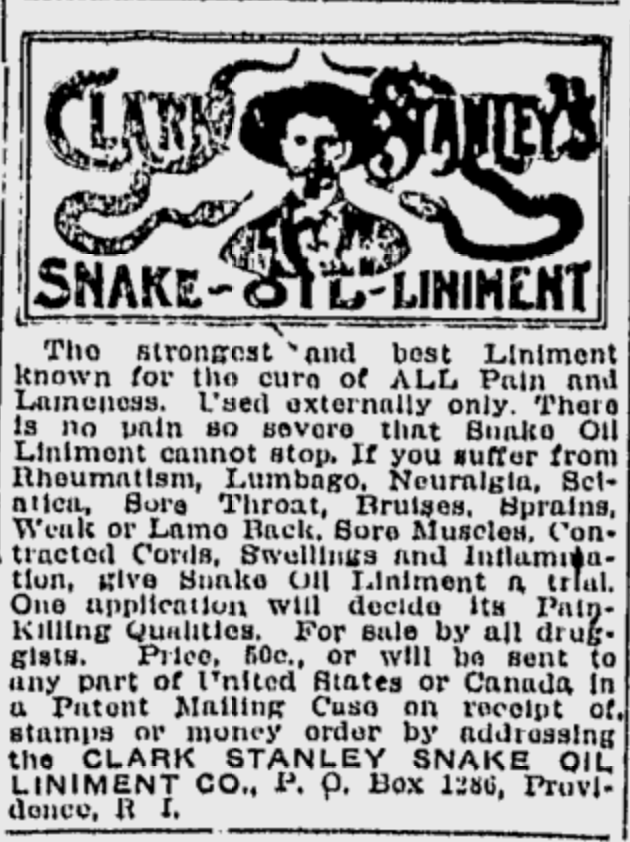

Aristide Leonides being the pivotal character in Agatha Christie’s Crooked House. Who, amongst other things, habitually twisted the law to suit his needs. Thus allowing him to skate just this side of trouble as he never technically broke the law. A tactic George successfully employed whilst setting up and administering his rum-running racket.

That being said, an unscrupulous streak that eventually grows wide enough to condone murder needs to start somewhere — generally, with minor misdeeds. Which you can find in George’s history. While still in Chicago, in April of 1913, George was officially charged of trying to bribe a witness during a divorce case, and in 1917, he was accused of conspiring to extort $15,000 from a prominent banker for breach of promise.

Though neither episode, as far as I can tell, resulted in any disciplinary action — the Illinois Supreme Court did disbar George on October 6, 1922 after his bootlegging conviction.

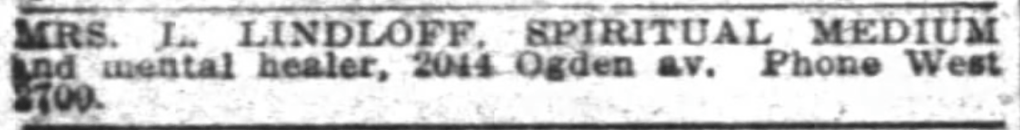

This moral malleability, I believe, reared its ugly head during Louisa Lindloff’s trial in October/November of 1912. For you see, until the morning of October 26, Assistant States Attorneys Lowe & Smith considered Ms. Sadie Ray their star witness. As Louisa’s housekeeper from approximately November of 1911 until Louisa’s arrest in June of 1912 — Sadie was on hand during Alma and Arthur’s last days.

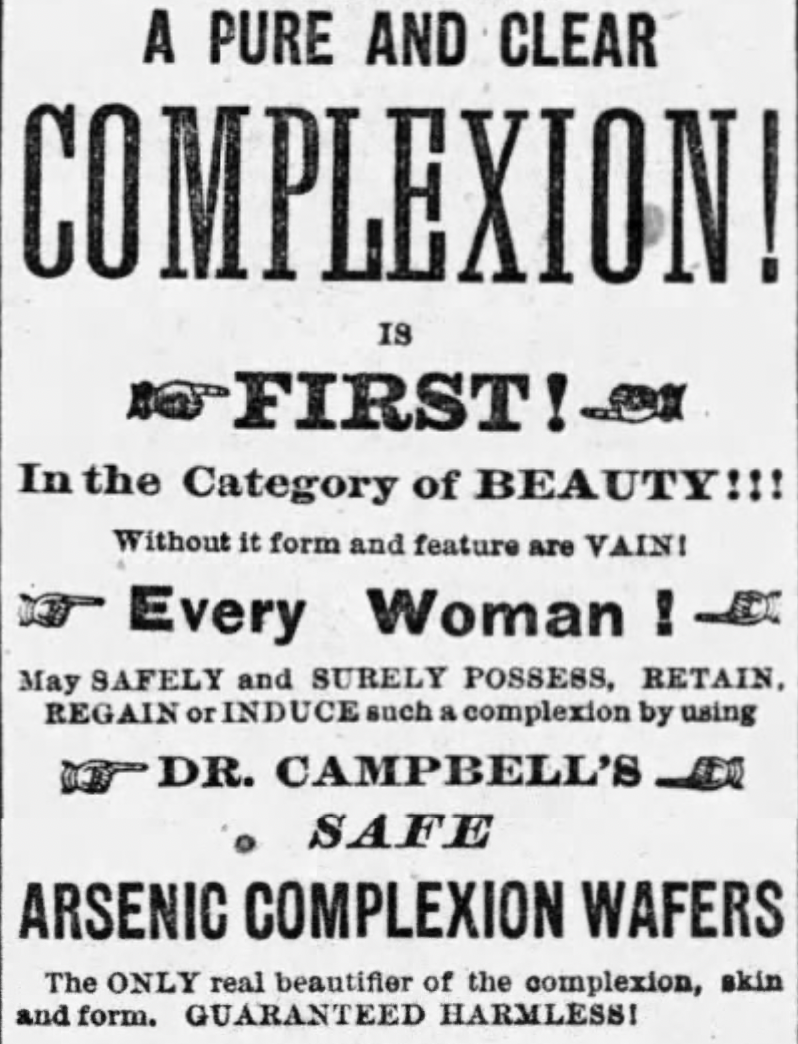

Though she didn’t testify before the Grand Jury, since the ASAs wanted some of their evidence to stay secret until trial, ASA Smith & Lowe did interview Sadie extensively behind closed doors. Where she told them, during her time at 2044 Ogden Avenue, that Louisa had not only predicted the date she would die — but advised Sadie to take out a life insurance policy naming Louisa as the beneficiary. After this conversation, which occurred only weeks before Arthur’s death, Sadie became seriously ill after eating a meal prepared by Louisa. Moreover, Sadie told the ASAs about the glasses of water Louisa gave Arthur, who in turn routinely complained about them being “sandy” and burning his throat. (FYI: Arsenic does not dissolve well in cold water, hence why the “sandiness” was so important.)

On October 26, 1912: However, when Sadie climbed into the witness chair, her testimony for the prosecution was lackluster at best.

Though she confirmed becoming sick after a meal at Louisa’s house and the insurance policy request, Sadie now recalled that Louisa only put the finishing touches on the dishes and that she’d actually prepared the bulk of the food. Sadie dulled her testimony about Arthur’s “sandy water” by tacking on that he was always “kicking off” about one thing or another during his final illness. When asked if she’d seen Louisa adding strange substances to Arthur’s food or refused to administer the medicine prescribed by his doctor, information the ASA’s seemed to expect affirmations of — Sadie replied, “I don’t remember.”

Let down by her information and suspecting undue influence, someone (apparently) put Sadie under surveillance.

October 29, 1912: This scrutiny that quickly bore fruit. When not only did one of Captain Baer’s men observe George Remus driving Sadie to court in his car, but (on another occasion) witnessed Sadie attempting to induce another state’s witness into accompanying her inside George Remus’s office building. When she refused, Sadie dashed into the building, returning minutes later with Remus in tow. Whereupon the legal professional began pressuring the witness to agree to testify that Louisa “had always been good to her family.”

When Capt. Baer confronted Sadie in a courthouse hallway with this intelligence and threatened to arrest her — she was defiant. “I’m a poor girl…Why shouldn’t I take an automobile ride when I have the chance?…I haven’t tried to influence anybody. And nobody has tried to influence me.” As for George, he claimed Sadie was a family friend, and the ride to the courthouse was just a simple “courtesy.”

The next day, George attempted to have Capt. Baer cited for contempt of court for trying to “intimidate” a witness. Although this gambit didn’t work, it did result in all the other state witnesses being put under police protection (as Sadie had been seen approaching others).

October 31, 1912: In a move that startled everyone present, George Remus recalled Sadie to the stand. During this second session of questioning — Sadie gave testimony that blatantly contradicted several remarks she’d made on the state’s behalf while calling Louisa a caring mother and corroborating Louisa’s assertion that both Alma & Arthur took patent medicine for a skin complaint that ran in the family.

Granted, it’s within the realm of possibility that Sadie’s memory grew a tad fuzzy in the three months before Louisa’s trial, and what Capt. Baer’s men witnessed was completely innocent — however, I don’t buy it. I think George either paid Sadie in cash or favor to tank her testimony for the prosecution and/or played on Sadie’s loyalty to Louisa to do the same.

Moreover, I don’t think this was the only testimonial U-turn George managed to buy.

November 2, 1912: When Mrs. Alvina Rabe (John Otto and William Lindloff’s mother) testified before a packed Chicago courtroom — she told the jury how kind Louisa was to John Otto, a good wife to William, and her belief that both her sons had died from natural causes. A stark contrast to her words during the Coroner’s Inquest in Milwaukee, when she called Louisa a murderer.

While no one, as far as I can tell, was ever charged with perjury, contempt, or witness tampering after Louisa’s trial. I find it difficult to believe that not one but two star witnesses for the prosecution serendipitously switched sides at the eleventh hour. Especially since we know from ensuing events that George wasn’t above bending/breaking the law when it suited his purposes. Whether by using a portion of the $59,000 (in today’s money) that Louisa’s supporters raised on her behalf or his silver tongue — I don’t know.

However, as Agatha Christie (might’ve) said: “One coincidence is just a coincidence, two coincidences are a clue, three coincidences are proof.” Though I don’t see a third (that doesn’t mean it isn’t there), I believe George Remus attempted to stack the deck in Louisa’s favor upon realizing how deep the waters against her were.

Not that it mattered.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.