Just some of the Christie mysteries containing arsenic!

Fun Fact: Did you know Agatha Christie used arsenic as a murder weapon, misled investigators with, or referenced the chemical element in nearly 25% of her mysteries? True story! However, ages before Agatha Christie earned the moniker ‘Queen of Poisons’ for her application of arsenic (and other equally baneful substances) within her books, people the world over were already well aquatinted with the element.

Saint Albertus Magnus, a Catholic Saint who was the first to isolate the grey metallic metal around 1250. Undoubtedly inspired by the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle’s writings on arsenic’s qualities (or sandarache as it was known in his time) and whose works Magnus commented extensively on.

Although the discovery of this dangerous substance is generally ascribed to the Patron Saint of Natural Sciences, Philosophers, Medical Technicians, and Scientists — Saint Albertus Magnus, awareness of arsenic’s deleterious effects reaches back further still to the Ancient Greek physician Hippocrates (b.460 B.C. – d.370 B.C.), who described the symptoms of arsenic poisoning he’d observed in some miners who’d dug into a mineral vein laced with the heavy metal.

Yet, even before the Father of Medicine noted the abdominal problems suffered by those miners, anecdotal evidence of chronic arsenic poisoning can be found in stories dating back to the Bronze Age — specifically, those tales containing the ‘lame blacksmith’ trope.

It’s believed the ‘collective cultural memory’ of this accidental and chronic arsenic poisoning is what inspired people to depict the Greek God Hephaestus and his Roman counterpart Vulcan (above) as being “lame” — as both were gods of metalworking, blacksmiths, fire, and volcanos. Hence why, he’s often depicted sitting down whilst forging the weapons of the Gods, despite the fact the ancient Greeks and Romans now worked primarily with iron.

It seems above and beyond the standard risks of molten metal, fire, and the perils of a mis-swung hammer — metalworkers faced an invisible hazard. When smelting copper ore (many varieties of which naturally contain some arsenic) or creating bronze by combining copper with arsenic (rather than or in addition to tin), a poisonous fume formed in the forge as the arsenic vaporized. Because arsenic is odorless, tasteless, and sufficiently soluble in hot liquids if mixed well enough (though this last quality probably didn’t come into play in this particular situation) — these metalsmiths had no idea they were habitually inhaling arsenic-polluted air….Until they started experiencing weakness and/or numbing in their legs and feet, difficulty breathing, and headaches — amongst other symptoms (before other diseases like cancer set in).

Thanks to the thousands of years between then and now, it’s unclear (or at least I’ve not found) when and who connected arsenic to the maladies commonly suffered by blacksmiths. Moreover, due to the ease in which both princes and paupers alike could obtain said element — the name of the first bright bulb who decided to rid themselves of an unwanted spouse/lover/relative/friend/enemy by mixing arsenic into their mulled wine or sprinkling it over their dinner plate has been lost to time.

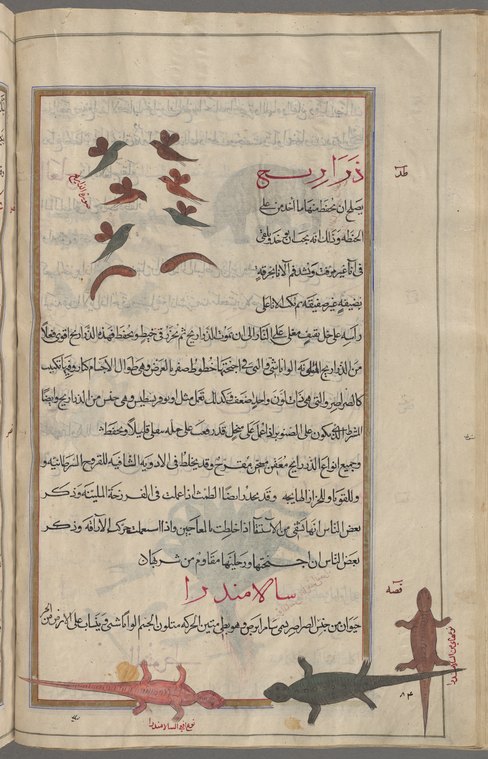

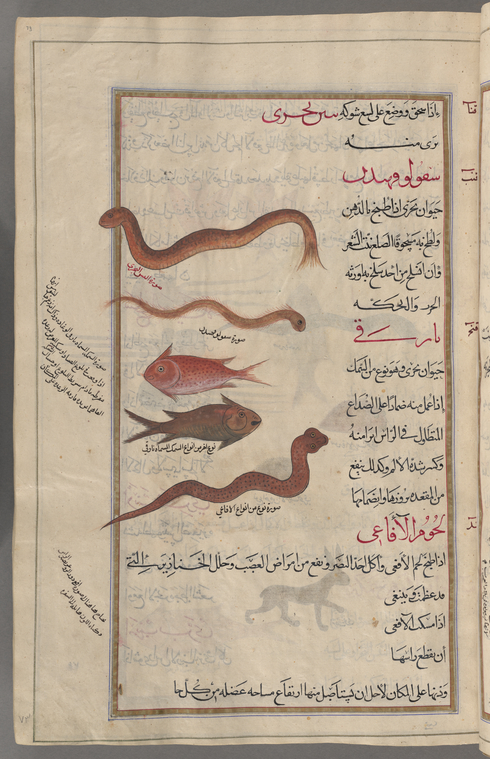

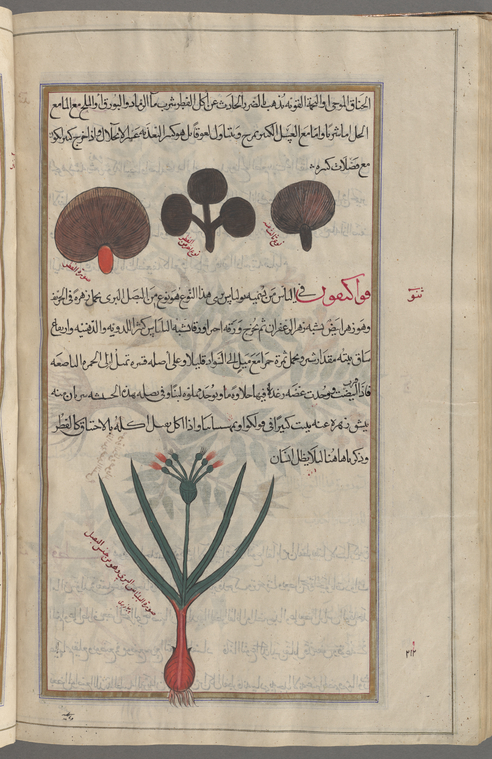

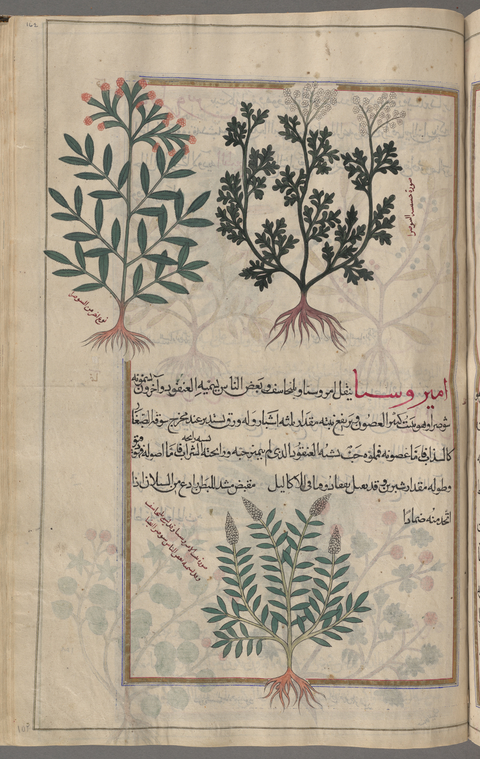

Pages from an Arabic translation of Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica, from L to R: A) Deadly Carrot B) Blister Beetles C) Hemlock D) Sea Dragons E) Deadly Mushrooms F) Varieties of Wormwood

That being said, we do know by the time Pedanius Dioscorides, the ‘Father of Pharmacognosy’ (or the study of medicinal drugs obtained from plants, animals, fungi, and other natural sources), published the fifth and final volume in his De Materia Medica around 70 A.D. — he described arsenic as a poison.

Knowledge Dioscorides could’ve obtained through first-hand experience as a physician in Roman Emperor Nero’s court.

It seems a few months after Nero was crowned in 55 A.D., the newly minted emperor used arsenic (or ordered someone else) to poison his thirteen-year-old stepbrother Tiberius Claudius Caesar Britannicus. As the biological son of the former Emperor Claudius and one-time heir apparent, Tiberius seriously threatened Nero’s own claim — hence, he had to go. (There is some debate whether arsenic or belladonna was used to do the deed. I lean towards arsenic, only because belladonna isn’t always fatal, and I don’t see Nero taking a chance that Tiberius might escape the assassination attempt.)

A pic of Nero.

After Nero’s act of fratricide, arsenic’s reign as the King of Poisons remained unchallenged until 1775. When Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele (of Scheele’s Green fame) devised a methodology to reveal arsenic’s presence in a person’s remains, although the corpse needed to be stuffed full of arsenic to produce a positive result, Scheele’s initial strides at bringing arsenic and its adherents to heel were significant.

Piling onto Scheele’s foray into toxicology was Johann Metzger. Who, in 1787, worked out a way to test if arsenic was present in a solution — but only if it hadn’t been consumed (picture the remnants of a half-finished bottle of pop, cup of coffee, or broth). Nineteen years later, Valentin Ross (or Rose; I’ve seen his name both ways) took Metzger’s technique one step further. In 1806, while pursuing a poisoner, Rose (or Ross) developed a way to process human organs (in this case, a stomach) that allowed Metzger’s test to be successfully run.

Next came the work of Mathieu Joseph Bonaventure Orfila, otherwise known as the ‘Father of Toxicology’. Amongst other advances in the field, Orfila refined Rose’s (or Ross’s) process, helping improve its accuracy. He also proved that after ingestion, arsenic gets distributed throughout the body. Orfila also aided in disseminating the work of Dr. Klanck, who, through extensive experimentation, determined the effect arsenic had on putrefaction and proved arsenic could be found in the remains of those long buried.

The cumulation of these various discoveries came in 1836 when a British chemist, James Marsh, became so vexed at the acquittal of a poisoner that he devised a more sensitive, reliable, and accurate arsenic test — which remained in use (with refinements) until the 1970s.

Unsurprisingly, with the gold standard in arsenic detection being developed, the abuse of arsenic was curbed — but not curtailed. And within this liminal space, Chicago’s Cell Block Tango, Agatha Christie, and Cook County’s very real Murderess Row intersect.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.