Back in 1984, NutraSweet introduced themselves to the world via a gumball campaign, where the company sent out a handful of spherical sweets to prove to the public it “tasted just as good as sugar”. Knowing they couldn’t send out the chewing gum and expect people to eat it — they preceded the mass mailing with an ad campaign letting everyone know what their mailers and gumballs looked like. Catching a couple of the commercials, I shrugged and returned to reading my Nancy Drews.

(Thanks to RetroTy for putting this old add onto Youtube!)

We never got anything that interesting in the mail.

Fast forward a few weeks to the day I opened our mailbox and spotted a familiar envelope lying inside — my heart skipped a beat. Lacking the means to buy candy on my own, as I was still in grade school at the time, I tore that envelope open in two shakes of a lamb’s tail. Popping the bright red gumball in my mouth, I began happily chewing away. Since checking the mail doesn’t generally include snacks, my mom immediately spotted my repetitive mastication when I walked back into the house and handed her the stack of correspondence. After a brief inquisition, in which my television defense was found wanting, the remaining gumballs were confiscated, and the piece I was happily snapping was consigned to the trash………….and my mom was MAD.

Yes, capital letters are necessary.

As a kid, I thought her reaction was blown way out of proportion. The tv commercial showed the envelope, the envelope we received was a match, and the sleeve of gumballs was unopened (I did possess some common sense) — so what’s the big deal? And let me tell you, that’s the exact wrong thing to say under your breath around an already irate mom. (I swear that woman possesses the hearing of a bat.) It wasn’t until recently, when I started reading and writing about true crime, that I finally understood the root of my mom’s eruption of MAD.

In point of fact, my mom wasn’t mad — she was scared.

What sparked her poorly expressed fear? Less than two years before the artificial sweetener’s spectacular introduction to American consumers, seven people died in Chicago via cyanide polluted pain pills. The first victim in the 1982 Chicago Tylenol Murders, which remain unsolved to this day, was only a couple of years older than myself when those gumballs landed in our letterbox. My mom, an avid mystery and true-crime reader (proving I come by my reading inclinations naturally), followed the case and knew of the rash of copycat killings it inspired — hence her fright at finding me chewing gum of “uncertain” origins. (BTW — I called her up and apologized a couple weeks ago for this long ago eye rolling transgression — she laughed and accepted it.)

Now what exactly does this have to do with the price of shortbread in Scotland?

Over the past few months, I’ve unconsciously gravitated towards books that, in one way or another, feature chocolates and mail. Sometimes together, sometimes separate, these two elements kept creeping into the narrative…..A box of chocolates laced with cocaine appears in Peril At End House (1932). In the short story The Chocolate Box (1923), Poirot figures out the murder weapon was a singe trinitrine (aka nitroglycerine) stuffed chocolate. Author Anthony Berkley injected nitrobenzene into the soft centers of an entire box of chocolates, sent thru the mail to an unwitting puppet, to complete the deed in The Poisoned Chocolate Case (1929).

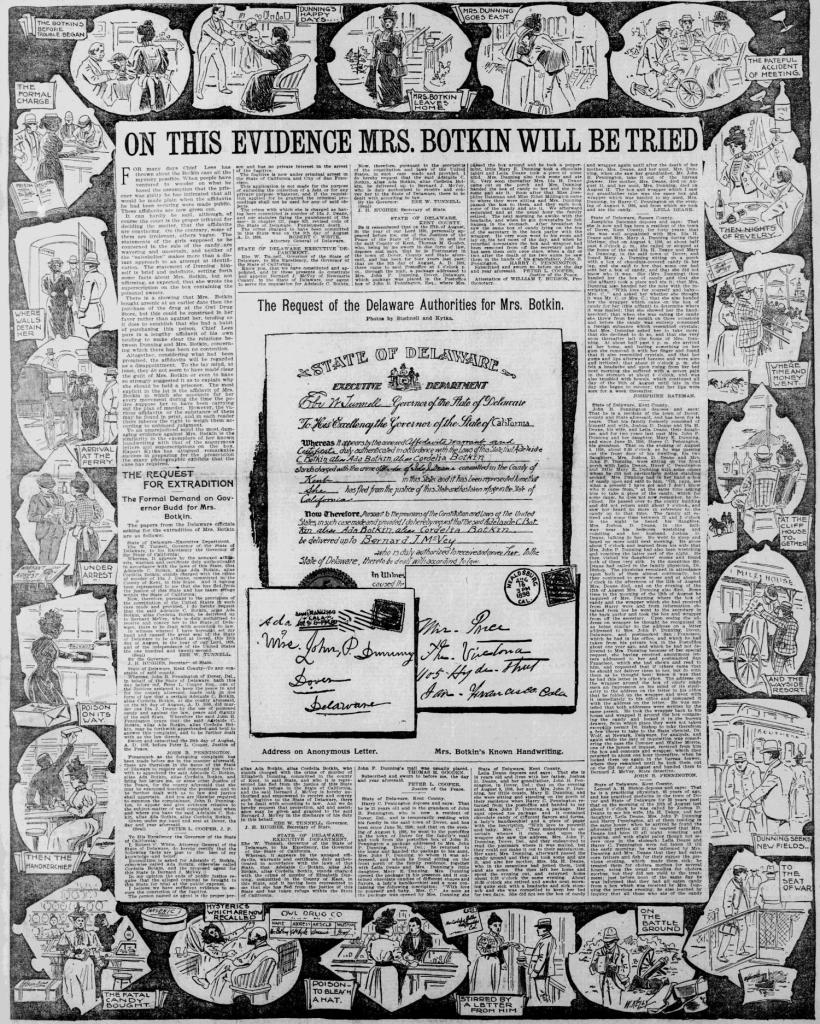

(From the San Francisco Call on September 15, 1898. One of the accounts of Cordelia Botkin’s deeds. I, unfortunately couldn’t find any pics of Christiana Edmunds.)

Following the heels of Berkley’s aforementioned mystery, I listened to Poisoner’s Cabinet’s (a brilliant podcast) take on the case of Christiana Edmunds (year of crimes: 1870 -1871). The Chocolate Cream Killer, as Christiana was later known, laced her favorite chocolate coated confections with strychnine, then left bags of the contaminated sweets all over Brighton in the hopes someone would eat a piece of uncredited candy and sicken. Thereby convincing her crush that the candy maker was responsible for poisoning his wife and not her (it was definitely Christiana, btw). Later in her career as an adulterationist, Christiana sent anonymous boxes of sweets, chalked full of her preferred poison, to prominent citizens of the same city.

(This last feature of Christiana’s crimes, of course, brought Angele Laval and her infamous letter writing campaign to mind. Thank the gods above and below that Umberto Eco’s book, The Name of the Rose, wouldn’t be published for another sixty-three years — otherwise, it might have inspired her to post literally poisonous, poison pen letters….But I digress.)

Hot on Christiana’s heels, though not actually, as there are several episodes betwixt the two explorations, I re-listened the Poisoner’s Cabinet’s alcohol tinged study of Cordelia Botkin (year of crime: 1898). Who first tried to dissuade her love rival with an anonymous note. When that foray fell flat, Cordelia sent her a box of chocolates overflowing with arsenic to permanently deal with her opponent.

Talking with my husband about these cases, I idly wondered: What on earth possessed people to eat candy they neither ordered nor expected to receive in the mail? Didn’t they see the danger? Indeed common sense and penny dreadfuls would warn people away from such behavior….That’s when I recalled the whole gumball debacle of my childhood, which made me curious. Since mysteries often reflect reality, and all the fictional crimes I listed above came well after my true-crime exemplars….How often (really) did candy get turned into a weapon before 1923?

Turns out a lot, and I will explore three true-crime cases linked by candy, poison, the postal service, and love-rivals over the next few weeks.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.