Captain Ahab & The Whale — a bleak tale about a great man who gradually immolating every part of himself on a pyre of obsession until all that remains is ash and a single all-consuming desire for revenge. Beyond laying bare a treacherous side of the human psyche, Melville’s masterpiece, Moby Dick, shows us how a person caught in the grips of a powerful obsession can justify nearly anything — including the sacrifice of a ship and its entire crew (save Ishmael). While I realize scouring the high seas for a giant white leg-eating sperm whale doesn’t occupy most people’s minds the way it did Ahab’s — it’s still a compelling tale…..and a cautionary one as well.

Especially when it concerns children.

Hyperfocusing on things like space, dinosaurs, books, animals, or other similar subjects is a well-known phenomenon. This intense interest in a single subject gives natural parameters for their exploration of the world while allowing their curiosity to flourish. This zeroed-in interest often dilutes or fades when they hit school — as they’re exposed to all sorts of new ideas, people, and tedium.

However, sometimes, just sometimes, a kid’s fascination takes a darker turn and doesn’t dissipate like so much smoke in the wind.

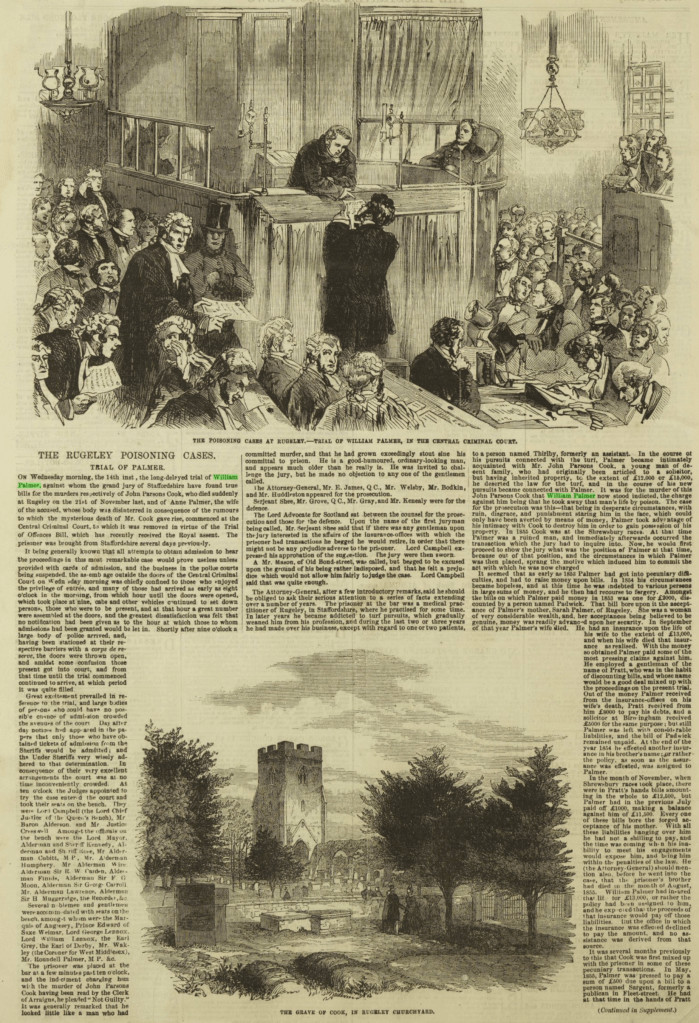

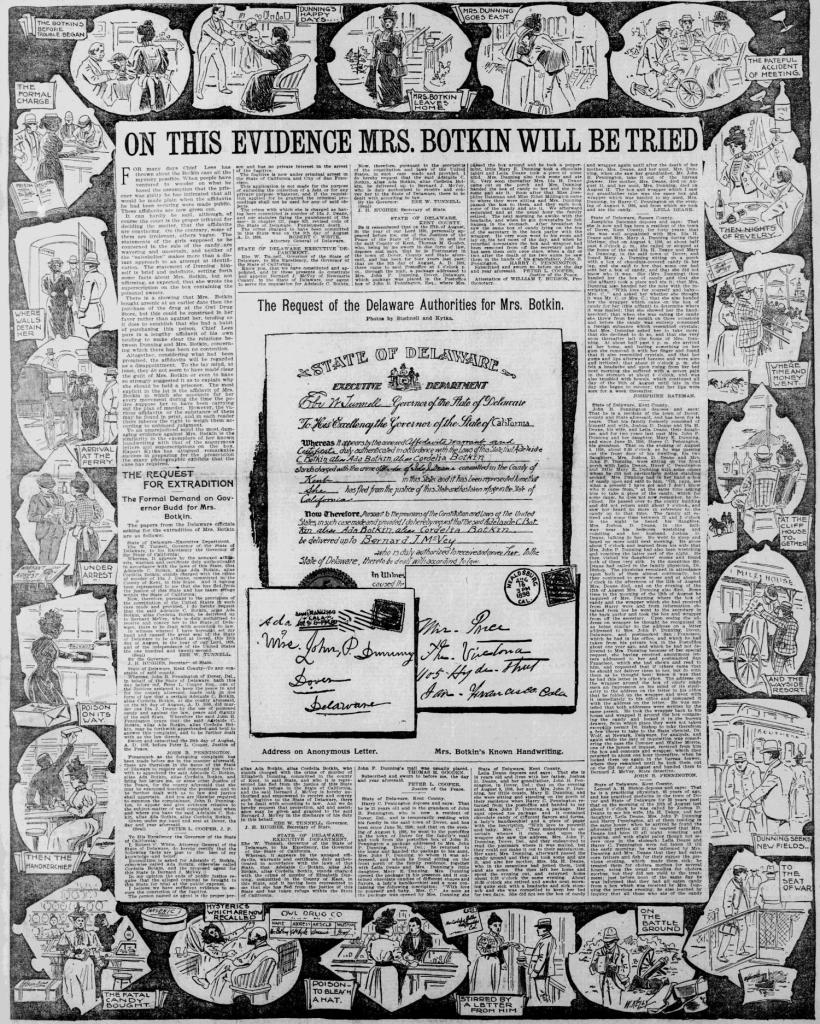

(The pics of the trial of William Palmer and the arrest of Dr. Crippen.)

Couple this all-consuming passion with immature moral muscles — you occasionally find yourself facing a kid like Graham Young. Who started wending his way down the pathway of obsession at an early age. It started with reading true crime (no biggie). Then, he became a fanboy of either Dr. Crippen or William Palmer and their poisons. (I’ve read accounts identifying one or the other as Young’s role model. Whichever way it went — labeling either as your idol isn’t exactly great.) Not to mention his enthusiasm for black magic and the Nazis.

Then Young found his calling.

At the age of twelve, Young entered secondary-school and started taking chemistry — which dovetailed nicely with his fascination with toxic metalloids, plants, and elements. At first, he satiated his idée fixe by studying books on advanced toxicology. Then, at the age of thirteen, armed with an extensive knowledge of both subjects — Young hoodwinked a local chemist into selling him antimony, digitalis, arsenic, and thallium.

Whereupon Young moved on to the practical application of poisons.

At first, Young experimented on a fellow student, but when the boy’s parents pulled him from school, Young moved on….And began conducting his research on his relations. Amongst other appalling familial poisoning episodes: Young sent his sister, Winifred, to the hospital by lacing her tea with belladonna. Next, Young committed what he thought of as a perfect murder by slowly killing his stepmother with thallium. (While Young confessed to Molly Young’s murder nine years later, this claim has never been verified — mainly because, at Young’s suggestion, her remains were cremated.) At Molly’s wake, Young tipped antimony into a jar of mustard pickles, sickening another relative. Finally, Young turned his full attention onto his father, whom he nearly sent to an early grave via antimony poisoning less than a month after murdering his stepmother.

However, Young’s preoccupation with poisons was not unknown.

Aware of the trouble befalling his family and others around him, Young’s science teacher searched his school desk and found several vials of poison and notebooks detailing things like dosages and symptoms. Taking his suspicions to the school’s headmaster, the two devised a trap: They arranged an interview between a careers counselor, who was actually a trained psychiatrist, and Young. During their discourse, the professional headshrinker managed to get Young to reveal his comprehensive and sweeping knowledge of his favorite subjects — poisons and toxicology. Weighing his troubling conversation against the spat of the “illnesses” plaguing those within Young’s sphere — the mental health professional took his misgivings to the authorities……Who saw fit to arrest Young on May 23, 1964, at which point they found his store of thallium and antimony.

In short order, Graham confessed, pleaded guilty, and became one of the youngest inmates in Broadmoor’s history at the age of fourteen. (For Those of You Who Don’t Know: Broadmoor’s the oldest high-security psychiatric hospital in England and second only in fame/infamy to Bethlem Royal Hospital, aka Bedlam.)

Pictures of Broadmoor the first is from 1867 and the second from 1952.

This change of address barely slowed Young down.

Soon after Young arrived at Broadmoor, another patient died after ingesting cyanide, a nurse discovered his coffee laced with toilet cleaner, and a caustic cleaning powder somehow found its way into a communal tea urn. Whilst an obvious suspect, Young was not brought up on charges in any of these incidences — as it’s unclear if he actually committed them. Young only ceased his claims of poisoning people during his incarceration after figuring out that if he feigned being cured of his fascination, he could win his freedom — which he did in 1971 at the age of (around) 24.

Unable or unwilling to eschew his love of bottles bearing a skull and crossbones, it didn’t take long for Young to return to his old ways.

Mere months after his release, Young once again secured an array of toxics — which he didn’t hesitate to dispense. By misrepresenting himself to a prospective employer, Young obtained a job where no one knew of his past offenses, which allowed him to poison with impunity. Before the shadows of suspicion thickened around him, Young administered thallium or antimony to his coworkers en masse via his tea trolly duties, targeting five individuals specifically and killing two others.

Earning him the moniker: The Tea Cup Poisoner — a nickname Young apparently loathed.

Thankfully, by the summer of 1972, Young was back behind bars — where he’d stay until his death in 1990 at the age of 42. (This is a vastly simplified history of Young’s life and crimes. For a more thorough account of his diabolical deeds, listen to episode #6 of The Poisoner’s Cabinet.)

Whilst the lion’s share of youthful passions don’t end up creating a poisoner, Graham Young demonstrates how many steps beyond the pale an idée fixe can take a kid. But here’s the horrible thing: whilst Young is one of the most infamous killer kids — he’s not the only one who’s journeyed down this treacherous path and left a body count in their wake…..

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.