Chapter 4: Dr. Edmond Locard vs. Tiger’s Eye

Whilst an amateur such as Miss Marple can gather evidence from wherever she chooses, including the dreams of Jerry Burton, even she knows such hazy evidence won’t hold water in court. Hence she, along with Megan Hunter and the police, engineered a sting operation to catch Mrs. Symmington’s killer red-handed.

Now if an amateur sleuth, albeit a gifted one, knows the musings of one’s subconscious won’t satisfy the court, then why on earth did Magistrate Richard think hiring a sorcerer, a hypnotist, and a medium was a good idea? Especially since, just ten years earlier, France’s first forensics laboratory was founded in Lyon. Needless to say, after the papers gleefully reported Magistrate Richard’s unorthodox investigative methods, he was summoned before his superiors to explain.

As this internal brouhaha played out in the press, a priest visited Angele Laval and her mother. At some point during his visit, he spied a half-finished letter sitting on a table. Familiar with Tiger’s Eye style, as he’d received at least one cankerous communique himself, he took this observation to the prefecture. Keen on ending the whole nasty affair, Commissioner Walter (who I think is the head of Tulle’s prefecture) confronted Angele with this information and attempted to cajole a confession from her — without success.

Meanwhile, as the case stalled due to Magistrate Richard’s absence, the great and the good of Tulle took matters into their own hands.

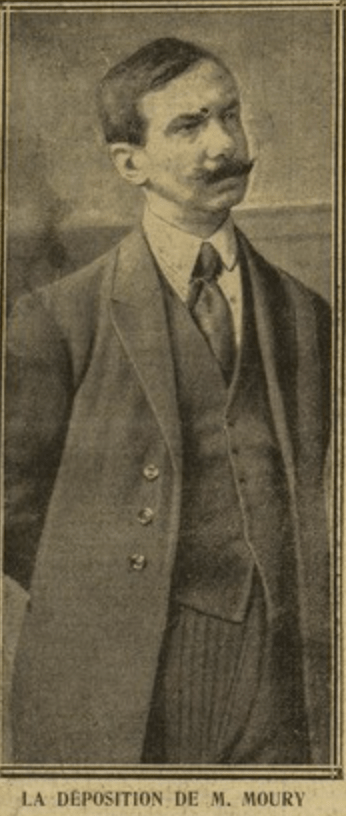

Contributing money to a fund, they hired the best forensics expert in France and the founder of the aforementioned forensics laboratory, Dr. Edmond Locard. (Whose principle is still used today — every contact leaves a trace.) Dr. Locard, at this point in his career, showed considerable enthusiasm for graphology — the study and interpretation of handwriting to build a psychological portrait of the writer. (Not to be confused with Questioned Document Examination, which focuses solely on the words on the page.) Interestingly, after his employment was secured, Dr. Locard found himself on the receiving end of about twenty anonymous letters accusing one person or another in Tulle of being Tiger’s Eye and one purportedly from Tiger’s Eye themselves asking if he could arrive in Tulle on any other day than Sunday, as they’d made plans.

Dr. Locard

With Dr. Locard’s recruitment, things were about to go south for Angele.

As it happens, modern experts agree with their fictional counterpart in The Moving Finger, “I can tell you gentlemen, I’d like to see something new sometimes, instead of the same old treadmill.” (pg. 88) It seems poison pen writers invariably employ the same tired mechanisms to disguise their handwriting: using all capital letters, writing with their off-hand, changing the slant or size of words, misshaped or deformed letters, employing different writing instruments within the same letter, altering how they dot their ‘i’ and cross their ’t’, pretending to be illiterate, or using cut out letters from magazines/books.

These techniques can successfully camouflage one’s handwriting, provided the author keeps their malice tinged missives short and sweet — so to speak. However, as a poison pen writer sinks further and further into their addiction, brevity generally isn’t within their reach.

Examples of Tulle’s Poison Pen Letters

Just look at Angele’s letters, overflowing margins, cramped lines — even the postcards are covered on both sides with words. Clearly illustrating what experts already know: poison pen writers are their own worst enemy. The longer the letter, the more likely it is that a lifetime of handwriting habits will start creeping onto the page — and — the longer they remain unnamed, the more confident they become, the more letters they send. Substantially increasing the odds, they’ll leave telltale signs of themselves somewhere in the script for an expert (and occasionally a motivated amateur) to find.

And let me tell you, Dr. Locard was given more than enough material to work with.

On January 16, 1922, after analyzing all the known letters, Dr. Locard summoned eight women to Tulle’s courthouse. Amongst the octette, all of whom were related to men present at the prefecture’s secret meeting, were Marie-Antoinette, Angele Laval, Angele’s Mother, Auntie, and Sister-in-Law.

Dr. Locard’s plan was simple.

First, he dictated select words and passages from Tiger’s Eyes letters while instructing the women to write them with both their dominant and off-hand. Then, after finishing these specimens, Dr. Locard asked the all female assembly to write four pages of capital letters. Although accounts vary slightly on how this writing exhibition went down, they all agree that during Dr. Locard’s initial short passage dictation, Angele didn’t falter. However, when asked to pen four pages of capital letters? Angele’s facade cracked, and it took her twelve minutes to write one line. Dr. Locard, a trained forensic scientist and keen observer, watched Angele repeatedly go over the string of letters, adjusting, augmenting, and adding little flourishes to her original hand.

Needless to say, Dr. Locard found this behavior highly suspicious.

Again it’s unclear if Dr. Locard let Angele go after finishing her lines and recalled her to the courthouse later that same day or whether he kept her behind at the end of the session — either way, the results are the same. Dr. Locard, determined to secure a genuine sample of Angele’s handwriting, relentlessly dictated the same passages at her over and over again. He purposely upset her by intermittently berating, shouting, and generally getting in her face. For hours he pushed her to write faster and faster, all the while ignoring her protestations of innocence, bouts of weeping, and occasional fainting spells. Eventually, by dint of sheer exhaustion, Dr. Locard procured several sheets of Angele’s genuine hand —thereby stripping her protective layer of anonymity away.

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.