Prescribed by doctors for a whole host of ailments including syphilis, malaria, leukemia, and general skin conditions — Fowler’s Solution was very popular. The fact its main ingredient was arsenic caused a whole host of problems for its users, as well as authorities in cases like Louisa’s. Though it had fallen from favor by 1905, it was still in use until the 1930s when it finally started phasing out of the US market.

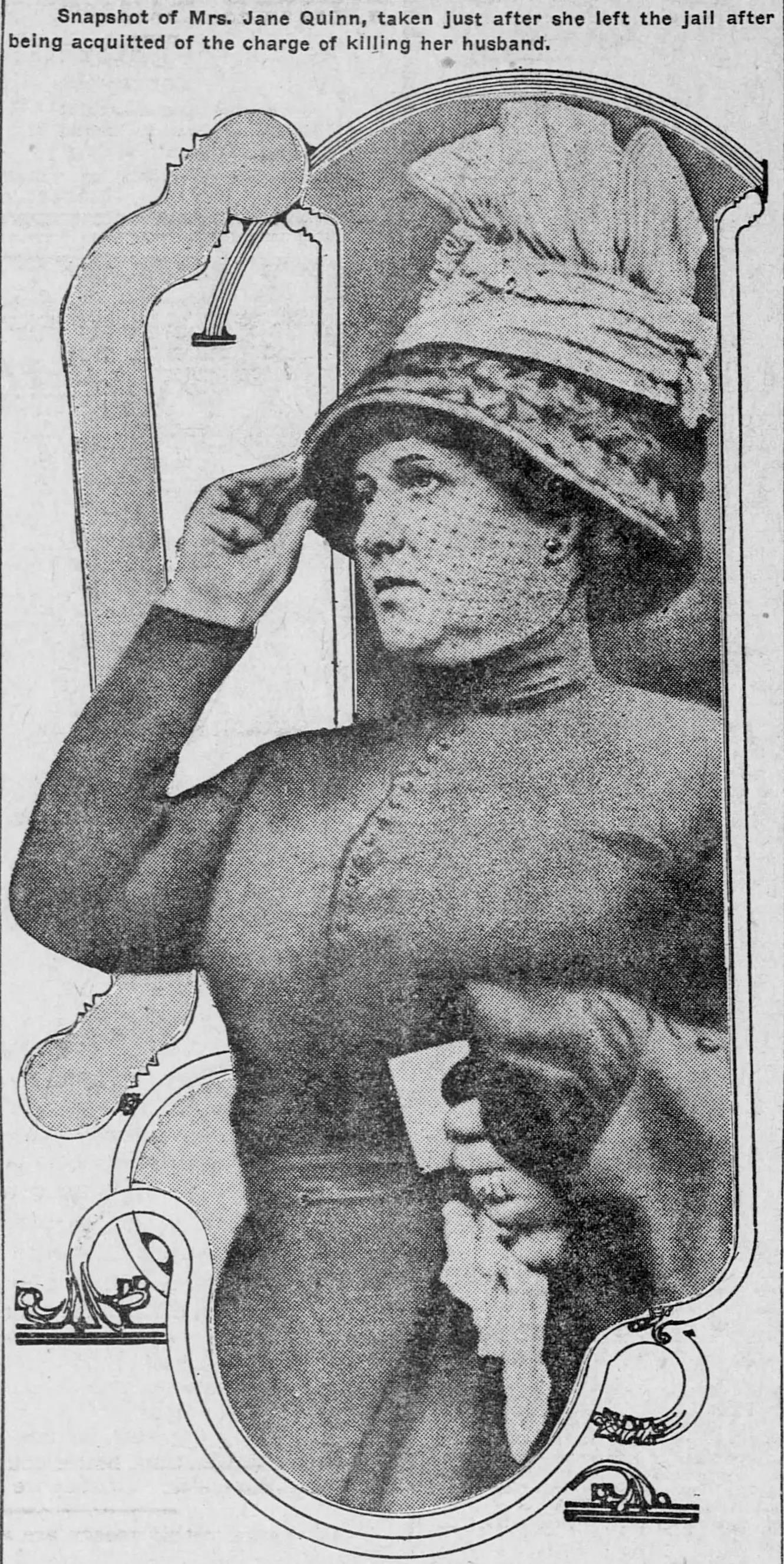

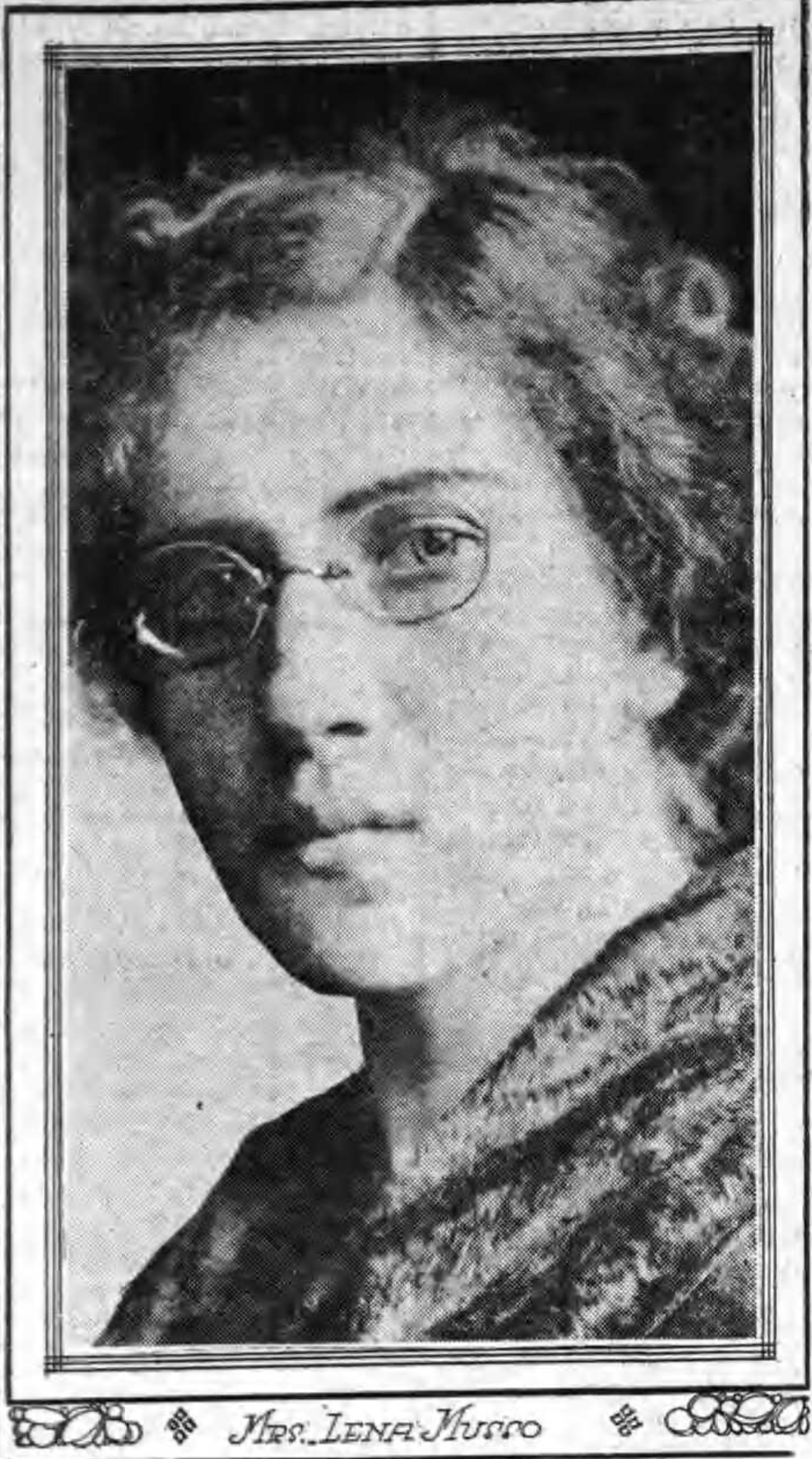

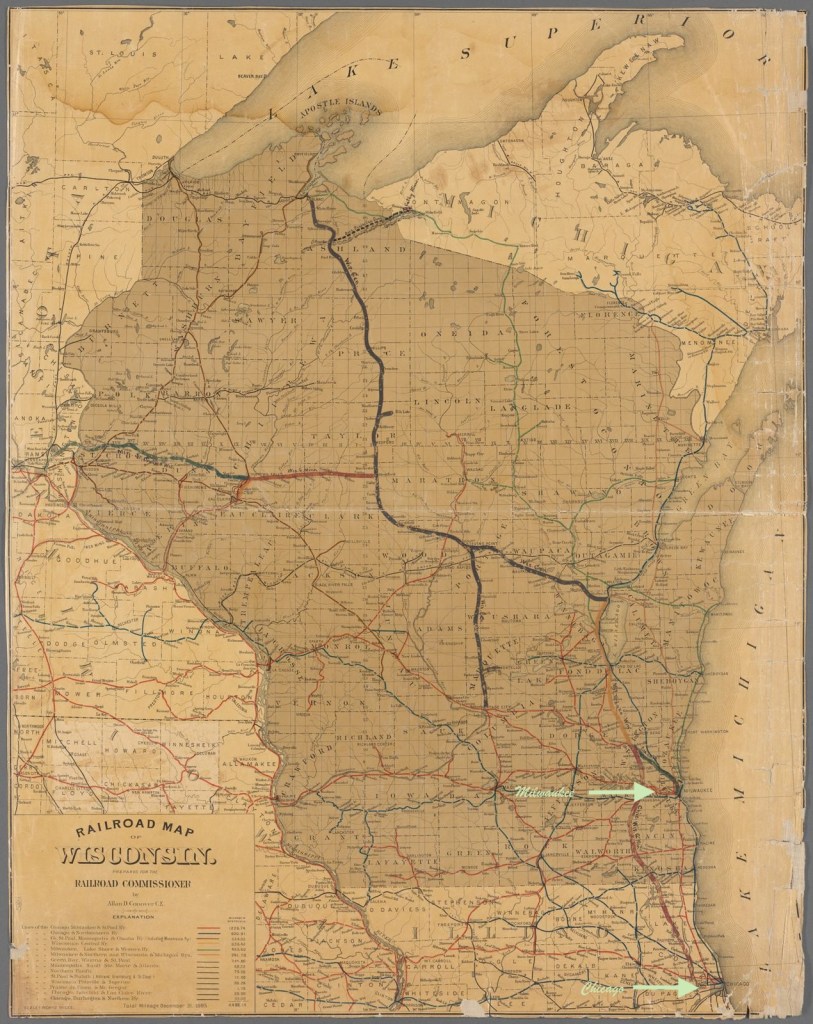

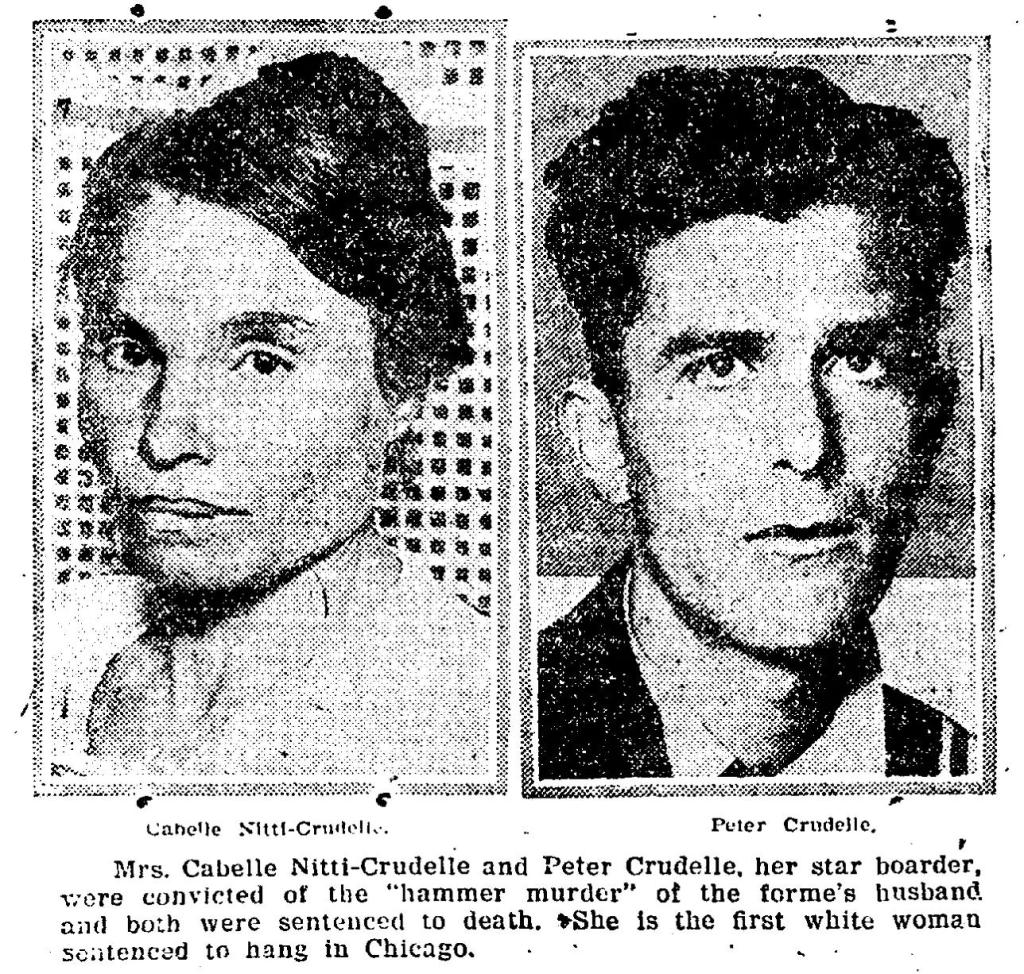

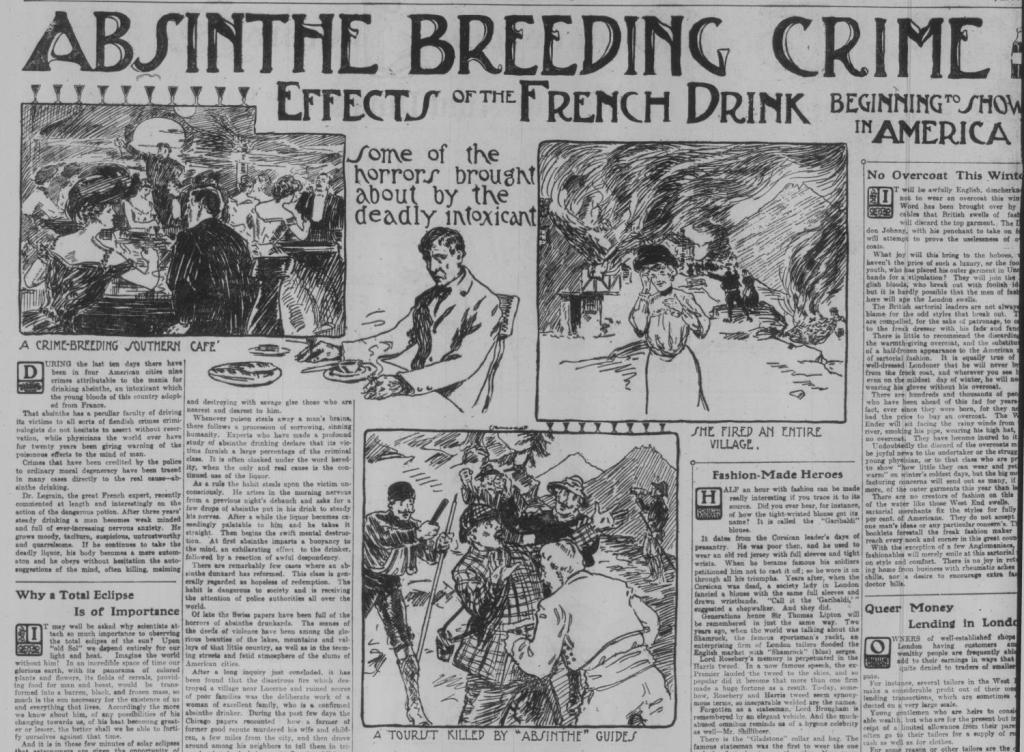

As we’ve seen, obtaining a conviction in historic Chicago was anything but certain. In 1912 alone, Assistant State’s Attorneys were forced to watch Florence Bernstein, Elizabeth Buchanan, Harriet Burnham, Rene B. Morrow, Lena Musso, and Jane Quinn walk out of Cook County courtrooms free as preverbal birds after (allegedly) shooting their husbands (and one love-rival) to death. Even the trial of Louise Vermilya, who police believed poisoned upwards of nine people, ended in a hung jury.

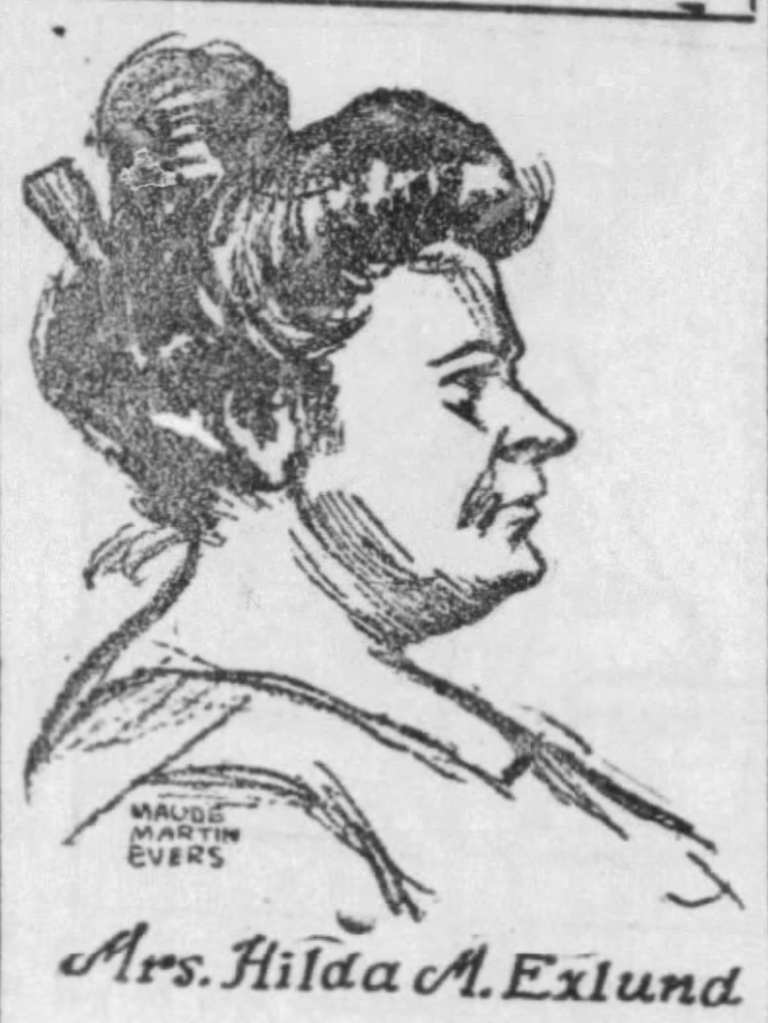

Four of the five women set free (at least) in 1912.

.….An outcome that undoubtedly buoyed Louisa Lindloff’s spirits, as Vermilya’s alleged crimes mirrored her own right down to the poison she favored, victim pool, and motive. (The two even shared a cell on Murderess Row for a spell.) Which begs the question, how? How did Vermilya flummox prosecutors and bamboozle six out of twelve jury members? And, more importantly, could Louisa improve upon Vermilya’s result and actually get away with murdering her son?

First and foremost, any claim of self-defense would most likely collapse under the weight of the days, weeks, and months of suffering endured by Louisa’s victims. By targeting her children Frieda (18y), Alma (19y), and Alfred (15y), Louisa pretty much rendered any and all claims to Chicago’s ‘Unwritten Law’ null as well as negating the idea of self-defense and a crime of passion. Unable to access any of the cornerstones of the Murderess Acquittal Formula while eyeing the swelling mountain of circumstantial evidence piling up against her, Louisa found herself in a tight spot.

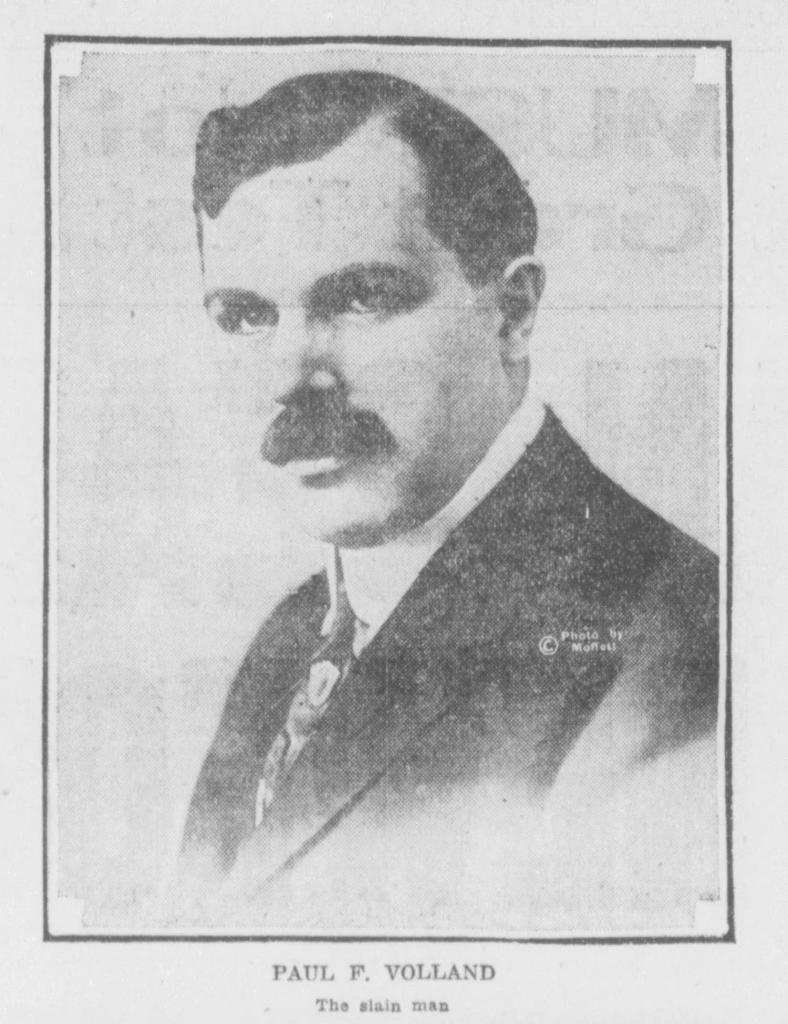

Until she hired famed criminal defense attorney George Remus.

Louisa Lindloff & her lawyer George Remus

Specializing in murder cases, Remus was undoubtedly aware of the blueprint others of his ilk used to defend accused poisoners. Tailoring this strategy to fit Louisa’s case, while cherry-picking from the remaining elements of the Murderess Acquittal Formula and adding his own flair, Remus’s first step was to undermine the state’s assertion that Arthur was purposely poisoned by Louisa.

The primary ingredient of Rough on Rats was arsenic.

Step One: Point out to one and all that owning arsenic, other poisons, and their derivatives isn’t a crime. Nor does their presence on a pantry shelf prove Louisa used them to harm those nearest and dearest to her. True, owning upwards of 80-plus bottles, boxes, and/or bags of said substances is a tad enthusiastic — but it’s not criminal.

Furthermore, such a collection could (nearly) be explained by the abundance of rats, bedbugs, and other disease-carrying pests who absolutely love urban centers, like 1912 Chicago. With the city’s overcrowded neighborhoods, uneven trash removal, and many restaurants, it ensured everyone from housewives to shopkeepers struggled to keep vermin at bay. A proposition made more difficult by rodents’ infuriating habit of developing poison shyness. (Hence why Louisa owned so many varieties.?! Maybe?) Plus, accidental exposure to Rough on Rats (and therefore arsenic) was almost inevitable due to the recommended application methods.

Photo thanks to: Eric Prouzet

Step Two: Call attention to the fact that arsenic is a naturally occurring element in the earth’s crust — which means — any arsenic found in the body could be due to natural exposure. Since Arthur’s employment didn’t entail any direct contact with soil (contaminated or otherwise), Louisa contended this incidental exposure came about through her son’s love of cucumbers, which he apparently “ate like a hog.” (Louisa’s description, not mine.)

While it’s true carrots, parsnips, and other such root vegetables can contain trace amounts of arsenic in their skins and, if not thoroughly washed, specks of arsenic-ladened earth can cling to their outsides — the same cannot be said of cucumbers. Between growing on vines rather than directly in the dirt and their thin skins — these vegetables contain very little arsenic in the parts we eat. Facts which could’ve rendered Louisa’s ‘cucumber defense’ shaky if: A. Scientists had discovered either detail by the start of Louisa’s trial on October 25, 1912. — And — B. If Assistant State’s Attorneys Claude T. Smith & Francis M. Lowes presented these scientific tidbits to the jury.

Step Three: Identify all the other ways the victim(s) could’ve come into contact with the deadly element.

Holding firm to Dr. Warner & Dr. Miller’s explanation that the wallpaper in Arthur’s sickroom was one source of exposure (despite their admission that this excuse was a ruse), Louisa added another legitimate wellspring – Medicine.

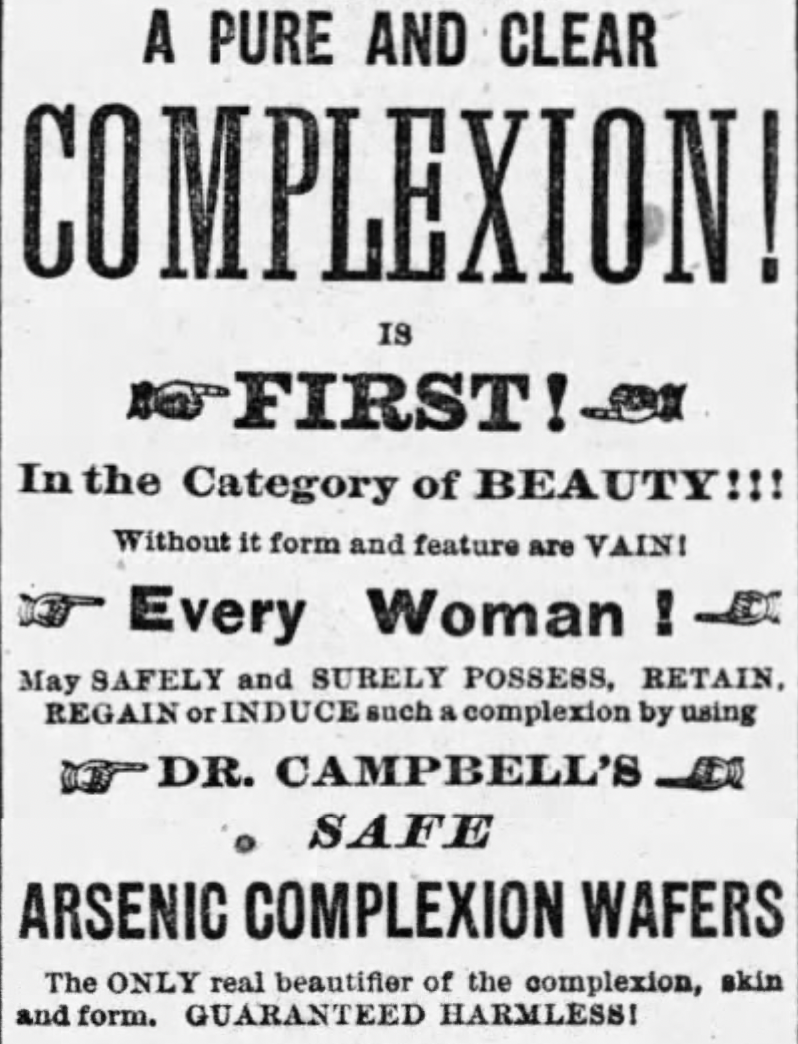

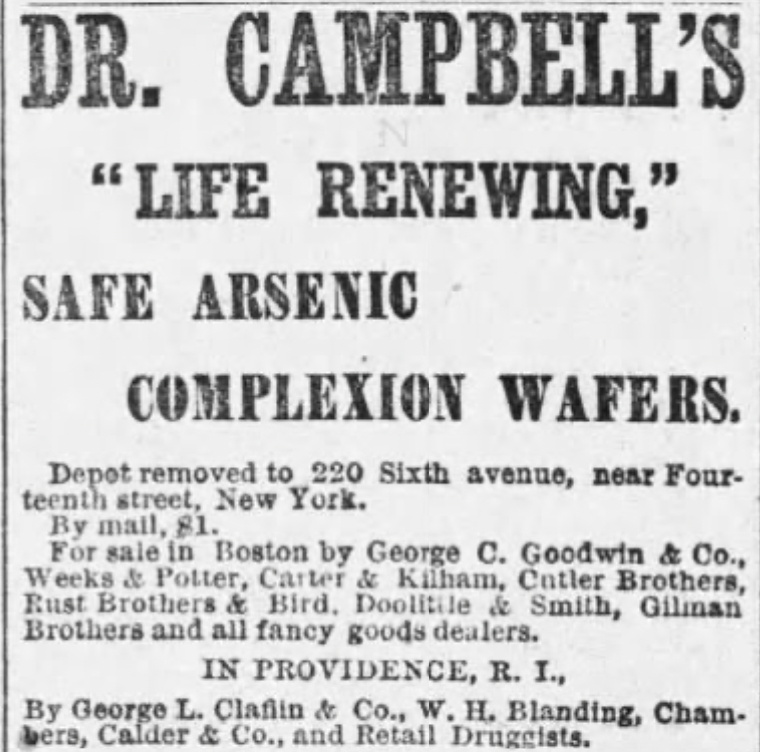

Above and beyond Fowler’s Solution, druggist sold arsenic wafers which were stuffed full of very real and very deadly arsenic to clear up one’s complexion.

According to Louisa: Arthur, his sisters, and her husbands all suffered from a skin complaint for which they treated with arsenic based patent and prescription medicines. Which Dr. Warner did confirmed prescribing.

From the Office of Full Disclosure: Prior to Louisa’s testimony at trial, the newspapers reported the family’s “hereditary skin complaint” in generic terms. It was only after Louisa took the stand that she euphemistically blamed her first husband, Julius Graunke, for passing on a venereal disease to her, which she, in turn, passed on to her children and her second husband. Perhaps she was alluding to herpes? Which was at one point treated with arsenic. However, thanks to reticence of the times when dealing with STDs, it’s unclear if the family actually suffered from said STD, an innocuous skin problem, or if Louisa invoked the idea to explain away the arsenic found in the bodies whilst simultaneously garnering sympathy from the jury.

Interestingly, unlike Louise Vermilya’s first trial, which was abandoned after a similar medicine based revelation, Louisa Lindloff’s continued.

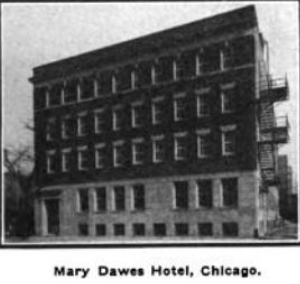

Another common way for substantial quantities of arsenic to enter the body: Embalming Fluid.

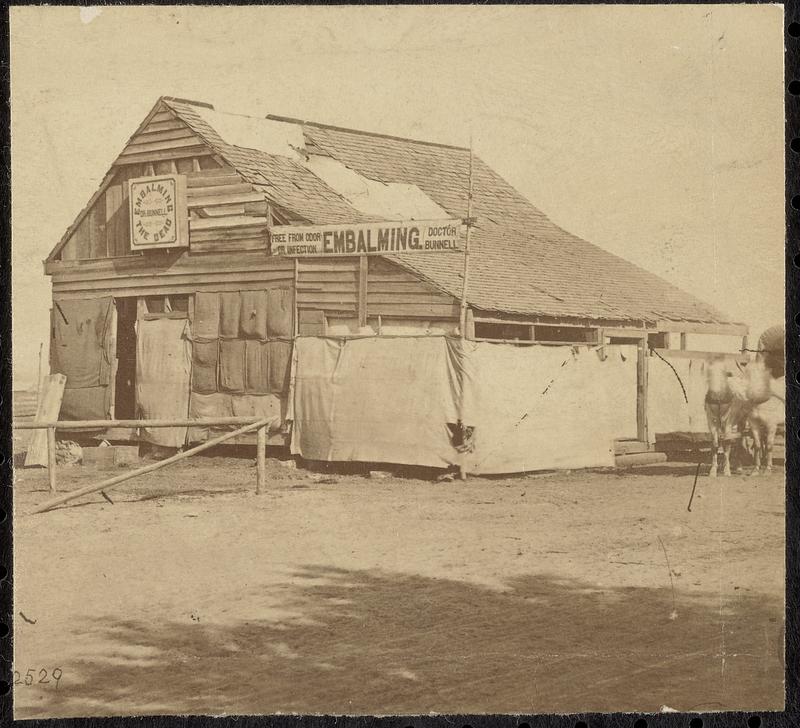

The Pictures from L to R: A) Dr. Thomas Holmes’s pic from Find A Grave.com. B) One of the instances where embalming fluid was used as a poison accidentally or on purpose in and of itself. C) The photo of the embalming barn was taken near Fredericksburg, Va. sometime during the American Civil War. D) 1906 article about Illinois undertakers trying to outlaw arsenic & strychnine as the active ingredient in embalming fluid.

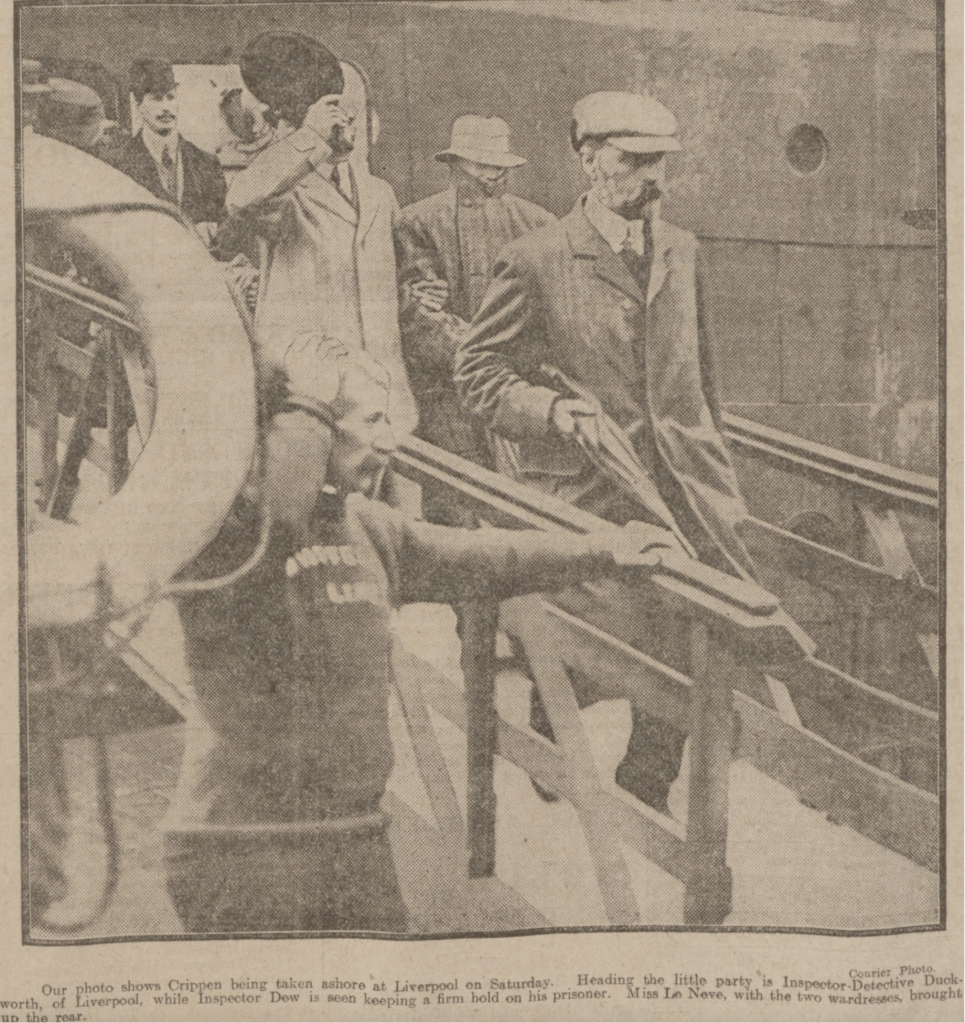

During the American Civil War, Dr. Thomas Holmes developed an arsenic-based chemical mixture, technique, and specialized apparatus to preserve Union soldiers’ bodies so they could remain (relatively) preserved during their journey back North for burial. When Holmes’ method proved successful, it was widely adopted. In cases like Louisa’s, the unintended consequence of this advancement in mortuary science is obvious. Since not even the most talented of chemists could differentiate between arsenic administered by nefarious means and arsenic used in embalming fluid, it often rendered results of the Marsh Test absolutely worthless in criminal poisoning cases where remains were tested after being embalmed and/or buried.

This detrimental side effect that reared its ugly head (again) on August 9, 1912. When Coroner H. L. Nathin was forced to abandon his inquest into Julius Graunke and John Otto Lindloff’s deaths due to the discovery that both sets of remains were treated with an arsenic based embalming fluid. (Charles Lipchow’s body was found bereft of the heavy metal. However, that does not mean Louisa didn’t poison him.) Thus ending the looming threat of extradition and prosecution, Milwaukee prosecutor’s promised should the notoriously fickle juries of Chicago acquit Louisa of murdering Arthur.

Speaking of prosecutors — they had their own strategy when dealing with multiple murderers like Louisa. Working under the assumption they could always try a poisoner for another murder, prosecutors would select their strongest case to take to court. Amongst Louisa’s many victims, ASA Smith & Lowes landed on Arthur as their best shot. Not only because his death was the most recent but on account of the quick thinking of two people.

Apparently, before Arthur’s body ever left Chicago’s University Hospital, Coroner Hoffman seized his pancreas and spleen following the institution’s post-mortem. After confirming for himself neither organ appeared diseased, thus ruling out the COD listed on Arthur’s death certificate, Hoffman delivered both organs to Professor Walter S. Haines of Rush Medical College for chemical testing.

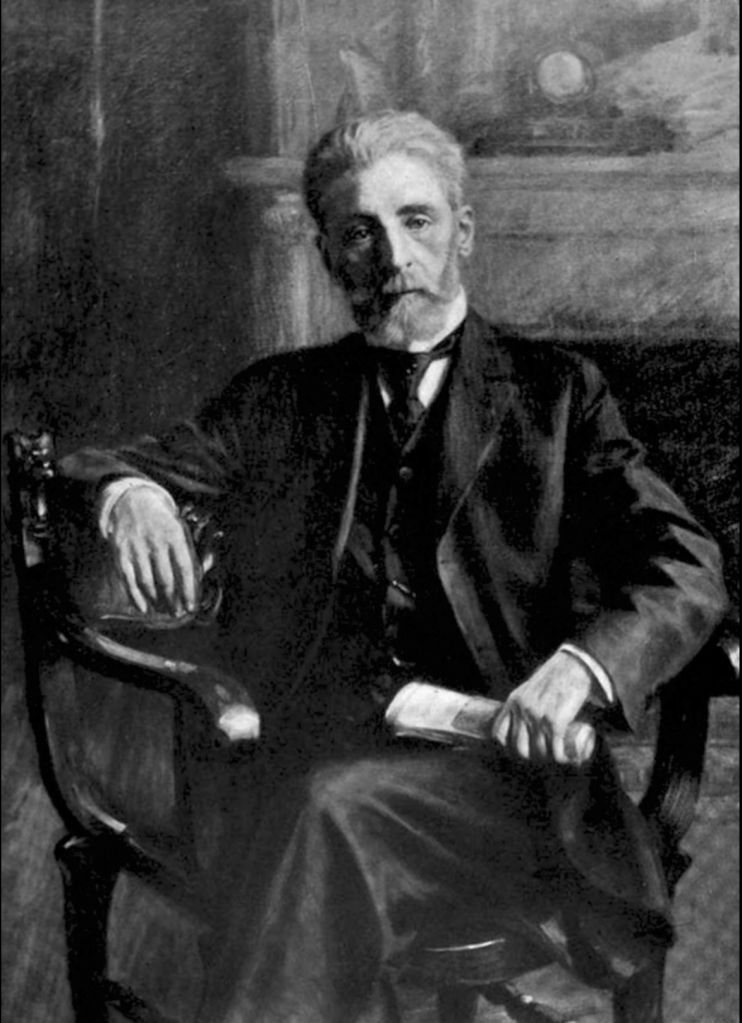

A portrait of Professor Walter S. Haines painted about 1916.

Upon Prof. Haines’ confirmation that both organs were chalked full of arsenic, Coroner Hoffman ordered the exhumation of William Lindloff and Alma Graunke on June 19, 1912. Although Illinois outlawed arsenic-based embalming fluid back in 1907, Hoffman also requested samples of the fluids used on William and Alma’s bodies be tested as well. Unsurprisingly, on June 27, Prof. Haines’ reported both sets of remains were brimming with arsenic and none was found in the fluid. Thus prompting Hoffman to disinter Freida Graunke’s body, which, in turn, yielded the same results.

Once More From the Office of Full Disclosure: At some point, Coroner Hoffman had Arthur’s lungs, stomach, liver, and other organs tested as well. Though, thanks to the sensation around Louisa’s arrest, it’s a tad fuzzy when precisely this happened. What we do know is, one way or another, Oak Ridge’s Undertaker heard about the kerfuffle around Arthur’s death, and rather than embalming the boy’s body straightaway — he held off. So when Coroner Hoffman arrived at the mortuary to collect the remaining viscera, he found it uncontaminated.

The Fourth & Final Step: Remind the jury arsenic is a cumulative poison, as well as, an acute one.

To this end, while testifying in her own defense, Louisa shocked the entire courtroom on November 2, 1912, by admitting Arthur and the rest of her family undoubtedly died with arsenic in their systems. Whereupon she blamed the accumulation of arsenic found in Arthur’s system on the boy’s overindulgence of cucumbers, the wallpaper in his sickroom, and doctors for prescribing arsenic based medicines.

As defenses go, it sort of held water….if you squinted at it really hard. However, the six grains of arsenic found in Arthur’s remains wasn’t the only damning element requiring an explanation.

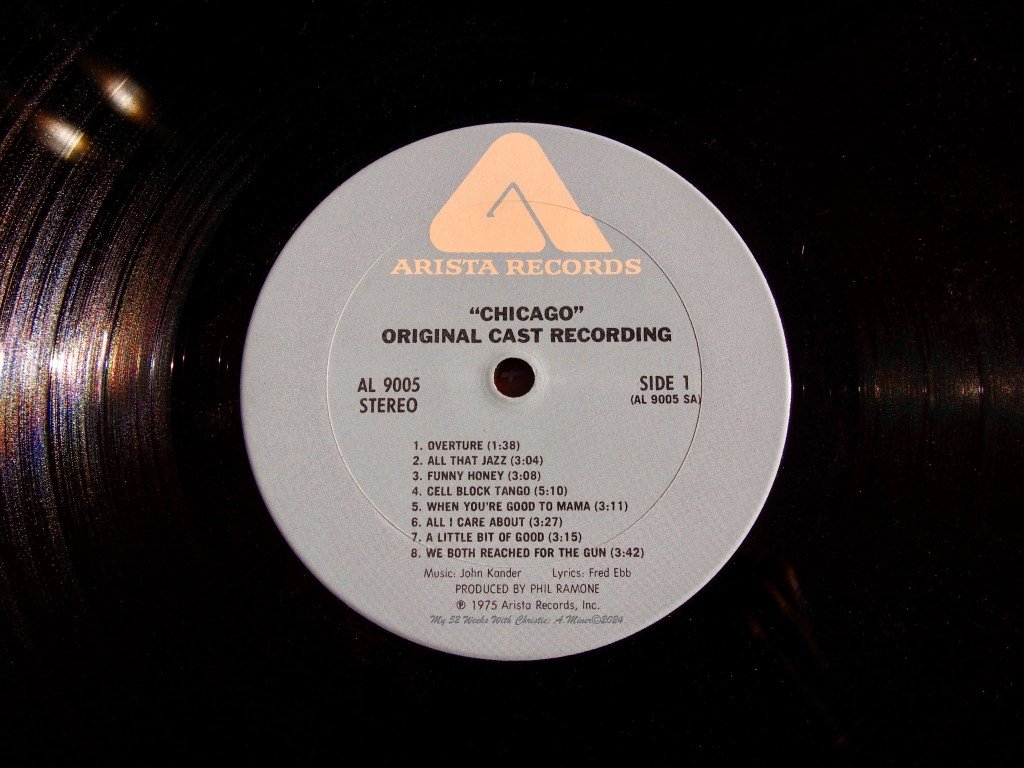

My 52 Weeks With Christie: A.Miner©2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.